To prepare for Please, Continue (Hamlet) we talked with a theater historian about the particular genre of show trials–plays that, through their production and form, interrogate ideas about judgement and the justice system.

Please, Continue (Hamlet), by Yan Duyvendak and Roger Bernat, isn’t a typical night at the theater. It’s a chance to see top-notch legal professionals in action, gain some insight into the workings of the legal system, and reflect on how we judge one another.

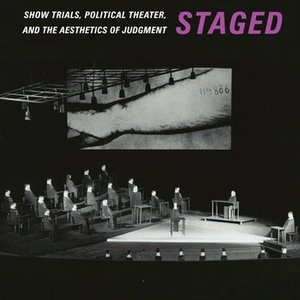

To help us prepare for this unique experience, we spoke with Dr. Minou Arjomand, Assistant Professor of English at the University of Texas at Austin, whose work focuses on theater history and whose recent book, Staged: Show Trials, Political Theater, and the Aesthetics of Judgment, theorizes the interface between law and theater.

"When we see theater, it can change us, even when the play is not explicitly about a social justice issue."

CHF: Let’s start with the framework for this play: what are some key moments in the history of this genre, show trials?

Minou Arjomand: Show trials have a long history in theater. In fact, the oldest complete Greek trilogy, Aeschylus’ Oresteia, ends with a courtroom drama. Orestes is on trial for murdering his mother Clytemnestra to avenge his father Agamemnon. And the question–which is also certainly relevant to Hamlet–is: how can we end a cycle of violence and revenge?

Playwrights from Shakespeare to James Baldwin have understood the inherent, dramatic power of trials and used it within their plays. Starting in the mid-20th century, artists and intellectuals have also developed forms that mix theater with law. Following the Second World War there was a wave of performances in both Europe and the United States that were based on (or sometimes performed verbatim) the transcripts of trials such as the Nuremberg Trials. During the Vietnam War, activists and artists including Bertrand Russell, Jean-Paul Sartre, Alice Walker, and Simone de Beauvoir held a tribunal accusing the United States of crimes against humanity, and passed their findings on the the United Nations. More recently, activists in the U.K. held a mock trial of Tony Blair for war crimes related to the War in Iraq, artists have created staged reading of the Guantanamo Tribunal Hearings in museums… the list goes on!

CHF: In 2019 CHF is exploring how power works across political, economic, historical, social, and interpersonal relations. How does power typically operate in a courtroom? Does a show trial re-configure those power dynamics–is that part of the form’s, well, power?

MA: In a courtroom, we can see power expressed in many different ways. There are costumes; for example, the judge’s robe, which signals her power to adjudicate. We see props: weapons in the belts of armed guards or police, the judge’s gavel. There is a set design that conveys the power of the judge and the justice system as well: a raised podium for the judge to sit on, or perhaps a bulletproof box around the defendant. In this sense, every trial is a show trial. And here I’m not using the term pejoratively, I just mean that–as Hannah Arendt remarked–for justice to be done, it must be seen to be done.

But there’s another sort of power that operates in the courtroom, and that is the power of narrative. Fundamentally, in the American court system, lawyers are working to each develop the most convincing story of what happened. To my mind, a key element that differentiates a show trial in the negative sense from a just trial is how free the lawyers and defendants are to create opposing narratives. In trials like the Moscow Show Trials under Stalin, for example, there was only one possible narrative and even the defendants were forced to confess and uphold that story.

CHF: In your book, you suggest that “while legal judgment can only address the past, theater can teach judgment as a continual process.” Is this capacity unique to theater, as opposed to other art forms?

MA: A courtroom trial is about the actions of the defendant: did they or didn’t they commit the crime? In some ways this is a good thing: too much emphasis on the historical context can mitigate the culpability of the defendant, like when former Nazis insisted in court that they should not be charged for mass murder because that was norm.

But sometimes leaving historical and political context outside the courtroom is also a problem: look at mass incarceration in the U.S. today. Your race, class, and neighborhood have a tremendous impact on how your behavior is interpreted, policed, and punished–so, ignoring this context isn’t the answer either. I don’t think that theater is going to redeem our criminal justice system. But I do think that theater projects, like Anna Deavere Smith’s recent play about the school-to-prison pipeline, Notes from the Field, are a way of presenting the broader context that is excluded in a trial. In this way, it’s not just a question of “did they or didn’t they,” but it’s about understanding how social structures impact people’s options. This sort of evaluation and judgement doesn’t have a yes or no answer, and moreover, it’s not a question but a public dialogue.

"Any individual can judge morality on their own; judging art requires taking other people into consideration and imagining how the world might look from their eyes."

CHF: Does that process of evaluating extend outside the space of the theater, as well?

MA: Theater is not just a place for a history lesson. I think that when we see theater, it can change us even when the play is not explicitly about a social justice issue: this gets to the relationship between legal judgment and aesthetic judgment, or a response based on feeling. And again, these are questions that go way back. The Enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant tried to figure out how different forms of judgment work: how is judging what is moral different from judging what is beautiful? The answer he comes up with is that morality is based on universal laws, and so to judge morally means to fit your particular case into a set of rules. This is how we understand what it means to follow or break the law today. But judging a piece of art is different because there is no set rule: we can’t say this painting follows these three rules and is therefore beautiful. Instead, Kant believes that aesthetic judgment requires a sort of common sensibility. You say “this is beautiful” because you imagine that it would be beautiful to other people as well.

CHF: Is the significant action, then, imagining other people’s responses to a work of art?

MA: Yes, this is the really striking implication of all this: it means that while any individual can judge morality on their own; judging art requires taking other people into consideration and imagining how the world might look from their eyes. There aren’t set rules, but a constant negotiation between your own impressions and your attention to the people around you. This may be true of all forms of art, but in theater this communal sense becomes all the more potent because you’re physically sharing space with other people.

CHF: This is connected to one of the through lines of your book–the importance of “liveness”–how being part of a live audience is crucial to forming judgments about others, because in a shared physical space, we may reflect on other people’s experiences. Does this mean that theater creates conditions to practice empathy?

MA: Who is sitting near us in a theater changes how we understand and react to what’s on stage. Many of us have probably had the experience of seeing something with a parent and the slow feeling of dread when you realize you made a terrible mistake–“I’m so sorry Mom, I didn’t realize this musical was an adaptation of Oedipus Rex set in a strip club!” On a more serious note, you might not laugh as loudly at a racist joke on stage if the person sitting next to you is targeted. Slapstick humor that mocks disability can seem mean and painfully awkward when you’re sitting next to someone in a wheelchair. Fat jokes aren’t as funny when your date begins cry. I don’t know that these experiences change people permanently, but if they force you to imagine the world from someone else’s point of view for just a few minutes, that’s valuable.

So yes, sometimes it’s about empathy, but sometimes it’s also about discomfort. I don’t want to sound too utopian here. Experiences with other people can be negative–you’re really enjoying a show, but the guy next to you keeps burping, the kid behind you is kicking your chair, someone is snoring...but we grit our teeth and figure out a way to share the space with them. And really, sharing space with people you may not particularly like, who you may find annoying–isn’t that what it is to be a part of a public? Courtrooms also try to figure out how we can all live together, but they use the threat violence and incarceration to make it work.

CHF: How is this cultural experience different from looking at public art, or film in the cinema?

MA: When we see a show trial, we witness two models of collectivity: on stage, we see the state itself determining who should be allowed to remain part of the public by judging based on laws. And in the audience, you yourself are experiencing and judging the play, based on, in part, who is sitting near you and how they are reacting. When it works, a critical dialogue can emerge between the objectivity required by legal justice, and the interpersonal relationships that might uphold social justice.

"Hamlet kind of has to die, doesn’t he?"

CHF: Do you have a favorite Shakespearean character? If you were a juror trying Hamlet for murder, how do you think you would respond?

MA: That’s a hard one! I’d definitely rather spend time with the characters in comedies...Beatrice from Much Ado about Nothing is pretty great. This may be an academic answer to your question: but Hamlet kind of has to die, doesn’t he? On the one hand, we’re on his side, but on the other hand, it’s clear that things are so foul in Denmark, there needs to be a new dynasty to consolidate power after all the murders.

CHF: What’s a present-day topic or individual that might be especially well-suited to the show trial format?

MA: I’m involved with an Austin-based company called the Rude Mechs that is developing a play right now called High Crimes: The Impeachment of the Worst President in U.S. History, which is based on the impeachment of Andrew Johnson. I’ll let you guess why that may have some contemporary relevance...

CHF: There’s a long history of art besides theater–literature, film, and beyond–that blurs the boundaries between the fictional and the real. What are some of your favorite works or artists in this category?

MA: I’m just starting a new project about radio and podcasts, and recently listened to Orson Welles’ broadcast of War of the Worlds–that one that had people all over the U.S. hiding in their basements, convinced that the martians had landed. It’s pretty fantastic.

Header image photo credit: Greg Noo-Wak

Dr. Minou Arjomand is an Assistant Professor of English at the University of Texas at Austin. Her research focuses on theater history, political theater, and the public role of art institutions. Her book Staged: Show Trials, Political Theater, and the Aesthetics of Judgment, was published in 2018 through Columbia University Press.

In partnership with the Museum of Contemporary Art, CHF presented a show trial in which Chicago actors performed the roles of Gertrude, Ophelia, and Hamlet, and actual members of the judiciary convinced a jury of you–the audience members–of Hamlet's guilt or innocence. There were four unique iterations of Please, Continue (Hamlet) spring 2019 and they were all fascinating experiences for theater, law, and literature fans alike.

Become a Member

Being a member of the Chicago Humanities Festival is especially meaningful during this unprecedented and challenging time. Your support keeps CHF alive as we adapt to our new digital format, and ensures our programming is free, accessible, and open to anyone online.

Make a Donation

Member and donor support drives 100% of our free digital programming. These inspiring and vital conversations are possible because of people like you. Thank you!