Do you have a spirit emoji? Is it 💃🏾? Or maybe you’re more of a 🔮? Or even a 🐒?

Whether you employ emoji in your everyday emails, texts, and tweets, or just send the occasional ❤️ to your significant other, the small pictographs are everywhere.

The original emoji 絵文字, which means “picture character” in Japanese, were created by Shigetaka Kurita in 1999. But it wasn’t until 2010 when Apple and Google adopted the Unicode Standard version 6.0 that emoji entered the global mainstream. They quickly catapulted to widespread prominence and are now a key component of modern communication, from the personal on Snapchat to the professional on Slack. And the extent to which emoji have invaded our social and cultural sphere in just a few years is evident in all kinds of consumer goods–you can make your family emoji pancakes; charge your phone with a surprisingly useful poop; keep track of your wine glass at parties; and cross stitch your favorite smiley face.

And if all this paraphernalia isn’t enough to show how omnipresent emoji are, back in 2015 one of the world’s leading authorities on the English language, the Oxford English Dictionary, declared 😂, “face with tears of joy,” the word of the year. You can read about the OED’s rationale and take a pretty sweet quiz to test how well you know your emoji.

But emoji are not interesting simply because they’re ubiquitous.

They’re interesting because of the ways in which they add nuance, attitude, and emotion to our digital communications, similar to the way gestures, body language, or facial expressions might add the right amount of sass or friendliness. Moreover, they exemplify how powerful design can change human behavior. Here we’ve articulated some critical questions that we found useful for contending with the social impact of emoji.

Emoji artwork | Standards Manual courtesy NTT DOCOMO

1) What’s the story of the original emoji?

The immediate precursors to our modern emoji were humble, 12x12 pixel designs of everyday things: a red heart, a present, an umbrella, a martini glass. Interface designer Shigetaka Kurita was 25 years old when he designed the first emoji while working at the Japanese telecom giant NTT DoCoMoin in 1998, and images soon exploded into everyday global digital communication. In 2015, the Museum of Modern Art acquired the original software and digital image files for the OG set of 176 images, enshrining the first emoji as a cornerstone of contemporary communication and design.

Yiying Lu, Dumpling art

2) How do emoji factor into digital inclusion efforts?

The Unicode Standard is the international standard that ensures that emoji characters are available and consistent regardless of the platform or operating system you’re using. Technically, anyone can submit an idea for a new emoji, but the thing is–the consortium is run by multinational tech companies. Enter Emojination, which seeks to make emoji approval an inclusive, representative process. Dumplings, birth control, high heels vs. ballet flats, and the hijab have all figured as part of the conversations around digital inclusion, not to mention the need for more gender and skin tone options without risk of being “taxed” for extra characters on Twitter. While emoji may seem like quite a small space to create change (literally), what’s at stake is broad-scale consciousness raising and action around digital inclusion.

Emojitracker

3) What’s global emoji use like on Twitter?

Looking at the nature and frequency of emoji usage on Twitter is a fascinating–if inherently over-simplified–gage of moods and conversations on social media. You can see patterns of emoji use with a tracker developed by Matthew Rothenberg, an independent artist. His Emojitracker updates emoji usage on twitter in real time. Warning: this site may be triggering for people with visual impairments.

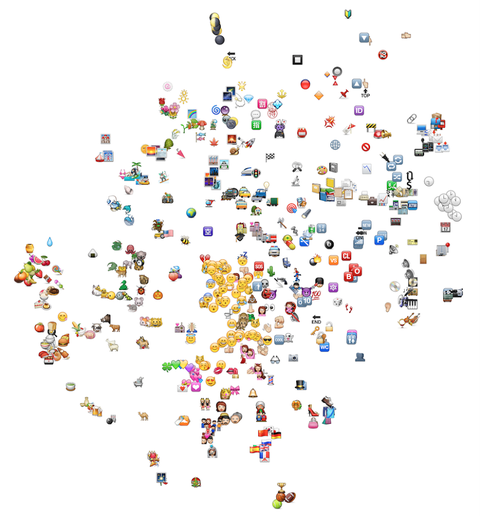

Semantic map of emoji, emoji are grouped by how often they are used together | Instagram

4) Are emoji rewiring our brains?

In short, yes–according to a study in the journal Social Neuroscience, it turns out that our brains perceive : ) in the same way we perceive a real human face. But, syntax matters: ( : doesn’t have the same effect. Technically, the : ) is not an emoji but an emoticon, using punctuation marks and numbers to create a pictorial icon. But because our brains process both emoticons and emoji as nonverbal information, we read them as emotional signals, not as words. And we already know that emotional communication is just as crucial to conveying meaning as words–so emoji are doing the emotional work that we’ve always done through hand gestures, facial expression, and tone. A 2015 study by Instagram also reveals how emoji usage is shaping our syntax–as emoji use goes up, internet slang like “lol” goes down, with users choosing smiley emoji instead.

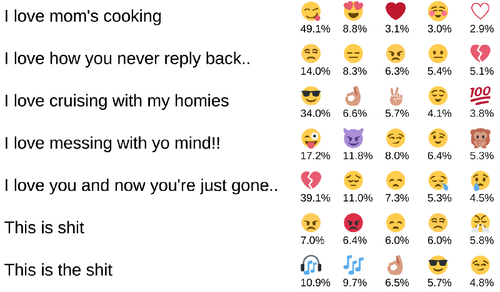

Bjarke Felbo | MIT Media Lab

5) Can an algorithm detect your emotions?

Natural language processing is an increasingly important part of AI and emerging technologies, bridging the gap between humans and heaps of digital data. MIT graduate student Bjarke Felbo thinks machine learning can help understand large-scale phenomena on social media, like bullying. And since emotional context is such an important part of language, he’s developed DeepMoji: a model that uses millions of tweets to learn about emotional concepts like sarcasm and irony. He situates this project in the larger context of sentiment analysis, suggesting that emoji analysis might be better suited to capturing more nuanced human emotion. Take DeepMoji for a spin and fulfill your civic duty to help AI learn the art of sarcasm (Alexa, could you be any more creepy?).

Sashank Santhanam | Emoji Understanding and Applications in Social Media

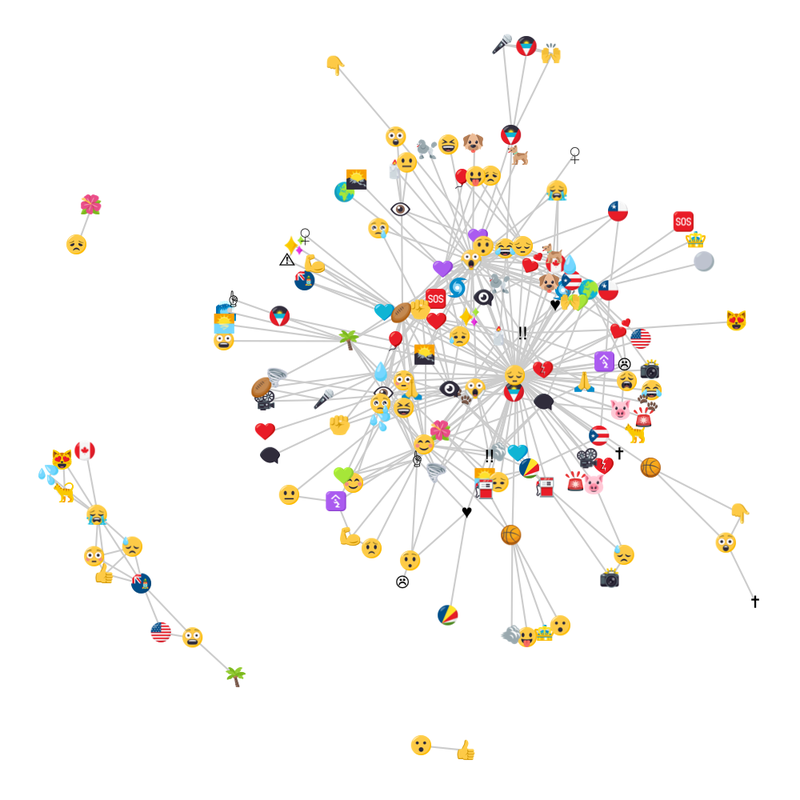

6) What’s the use of emoji in times of crisis?

When tragedy strikes, how does emoji usage change? A recent study suggests that emoji are a powerful indicator of sociolinguistic behavior–solidarity–that are shared on social media as crisis events unfold, such as during natural disasters or terrorist attacks. Observers prefer to express solidarity with those in crisis through tweets using non-face emoji–predominantly prayer hands, hearts, and flags–which may reduce the possibility of ambiguity. And in the realm of suicide prevention, machine learning assessment tools have made it easier for researchers to analyze conversations and look for signals that someone may be close to attempting suicide. Data scientists at Crisis Text Line, a text messaging-based crisis counseling hotline, learned that the crying face emoji is 11 times as predictive as the word “suicide” that someone might need an active rescue. And other platforms, such as Facebook, are starting to roll our AI programs to detect mental health risks.

7) Do emoji indicate a degradation of language?

Remain composed, loyal logophiles: logographic writing systems (those based on pictures or characters) are not degradations of alphabetic writing systems (and actually it’s pretty racist to assume as much). Most language specialists agree that emoji are used to augment, enhance, and add complexity to text, just like intonation and gesture might do for spoken language. We should remember, too, that the earliest written languages were logographic (like cuneiform and hieroglyphics)–though linguists would remind us that emoji are technically ideograms, with each picture representing an idea rather than a single word.

8) So...are emoji in fact their own language?

😑 = I don’t know.

😑 = I don’t know, but I want you to think that I do know and I’m hiding it.

😑 = I know, but I don’t want you to know that I know.

😑 = I might know, but I don’t want you to know that I know or care.

😑 = I know, and want you to think I know.

The 😑 is beautifully polysemous. And although it’s a contentious question, most linguists suggest that emoji don't constitute a separate language, but are a complex system of pictographs that expand our communication with nuance and emotion. They may not have a fixed syntax, but they can convey spatial relationships. Just like actions, facial expressions, or gestures, emoji are polysemous–they have multiple meanings (🤷🏾♀️). So ultimately, emoji may not exactly “speak” louder than words. But by signaling particular attitudes and expressing specific emotions, emoji can enable us to communicate more capably.

9) Bonus question: Can emoji function as criticism?

Yes! See the emoji-only review of The Emoji Movie, which is as much a movie review as it is a statement about branding and late capitalism. 💯

Become a Member

Being a member of the Chicago Humanities Festival is especially meaningful during this unprecedented and challenging time. Your support keeps CHF alive as we adapt to our new digital format, and ensures our programming is free, accessible, and open to anyone online.

Make a Donation

Member and donor support drives 100% of our free digital programming. These inspiring and vital conversations are possible because of people like you. Thank you!