Protest has long been a staple of grassroots resistance to the status quo. But what gets lost when protests become more mainstream, even viral? Are we living through a "Golden Age of Protest"? And just how potent is protest as a tool for social change in the 21st century?

Are we experiencing a “Golden Age of Protest”?

Ongoing democratic struggles and the recent emboldening of the far-right have prompted a full-blown revival of traditional protest tactics, jacked up by 21st-century media and technology. In early 2019, protests helped topple the 30-year rule of Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir and internationally coordinated student strikes and mass demonstrations across six continents to call for climate action.

Since the 2016 US general election, Americans have hit the streets in unprecedented numbers. Repping a range of issues and causes – from anti-racism to environmentalism, gender equality to immigrants rights, gun control to the living wage – millions of protestors have led more than 20,000 demonstrations, including one boasting the record for the largest single-day turnout in the nation’s history with the multi-city Women’s March. It would seem then, as one optimistic organizer put it, that we are living through a “Golden Age of Protest.”

Everyone from A-list celebs to elementary school kids, fast food workers to CEOs are embracing the Activist mantle. In the past decade, we’ve seen a surge of protests going viral. When an anti-government protest in Tunisia helped launch a series of regime-toppling uprisings around the Middle East in 2010, referred to as Arab Spring, it helped inspire Occupy Wall Street – sparking nearly 1,000 occupations against economic inequality worldwide. Protest became a near-constant feature of the news cycle, leading TIME Magazine to declare “The Protestor” as their 2011 “Person of the Year.” Since then, protest movements are not only embracing the viral potential of the hashtag, hashtags are actually giving rise movements – notably, #BlackLivesMatter and #MeToo sprung up from single, zeitgeist-capturing posts.

Protest has historically played a major role in securing many of the laws and policies we now take for granted. Can it affect policy change today?

Protest, or, the organized public demonstration of dissent, has historically played a major role in securing many of the laws and policies we now take for granted. We have it to thank for an eight-hour working day, women’s suffrage and the end of legal segregation. By the 20th century, nonviolent protest had become the go-to tactic for social movements. Leaders who famously preached and practiced it – Susan B. Anthony, Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks, Nelson Mandela – rank among the most beloved global icons.

Though these heroic figureheads have been retrospectively lionized, their victories were the results of long, patient, collective movement-building fraught with setbacks and backlashes that constantly threaten their achievements. When protests succeed, they affirm our democratic faith that “people power” will ultimately triumph over that of the ruling elite. When they fail, they expose the radical inequalities in how power is actually distributed.

Recent protests have indeed yielded their share of disheartening failures. One oft-cited is the anti-war protests surrounding the US-led invasion of Iraq. In fact, February of 2003 saw the world’s largest ever turnout for a coordinated international protest when more than ten million people in 60 countries came out to demonstrate against the looming Iraq War. A month later, the US invaded. More recently, the optimism of Arab Spring has been supplanted by oppressive returns to the status quo along with bloody and bitter civil wars. While some argue that Occupy made a significant invention in public discourse, many lament the lack of tangible policy change it inspired. Not only is income inequality on the rise, regulations introduced following the Financial Crisis are steadily being rolled back. Standing Rock didn’t stop a gas pipeline being built; Black Lives Matter has resulted in three convictions related to police shootings of unarmed black men; and we still have a president accused of sexual assault who is still apparently going to build a wall.

Is protest an effective and inclusive expression of people power?

So, just how potent is protest as a tool for social change in the 21st century? Is it really an effective, valid and inclusive expression of people power? What is gained and lost when protests go “mainstream”? Is it more strategic to focus on single issues or to form diverse coalitions that embrace the connections among struggles?

If protest is indeed an effective political strategy, how are today’s rapid advancements in technology and global connectivity amping up or curtailing its power? Does social media extend the reach and influence of a protest while creating new opportunities for solidarity, or does it merely expand the opportunities for surveillance and repression while substituting real political engagement for superficial “clicktivism”? Can for-profit platforms (often majority-owned by the world’s richest men) really enable democratic resistance?

And, what role do the arts and letters have to play in protest, especially in an era when such dissent has gone digital and mainstream? Is protest an art and should art be protest?

The following syllabus is a starting point for reflection and dialogue on these questions. It includes a few historical references but is heavily weighted towards contemporary thinkers and conversations. Every source on the recommended reading list is linked and available online for easy access. Do you have a suggestion to add? Let us know!

Abernathy Family Photos | public domain

WEEK ONE: THE POWER OF PROTEST

“What are the consequences when people refuse their roles and become disruptive? Perhaps disruption is not only born of desperation but is in fact a source of power.” –Frances Fox Piven, political scientist

Mahatma Gandhi, “The Practice of Satyagraha (Civil Resistance),” Selected Writings (1938).

Gene Sharp, “198 Methods of Nonviolent Protest and Persuasion,” and an excerpt from his book, Waging Nonviolent Struggle: 20th Century Practice and 21st Century Potential (2005).

Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan, “Why Civil Resistance Works,” International Security, Summer 2008.

Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Declaration (2012).

Julian Brave Noisecat, “The Indigenous Revolution,” Jacobin, 24 November 2016.

Sarah Jaffe, Interviews for Resistance podcast (2017-present), and Necessary Trouble: Americans in Revolt (2016).

Frances Fox Piven, “Throw Sand in the Gears of Everything,” The Nation, 18 January 2017.

Srdja Popovic and Greg Satell, “How Protests Become Successful Social Movements,” Harvard Business Review, 27 January 2017.

Rebecca Solnit, “Protest and Persist: Why Giving Up Hope is Not an Option,” The Guardian, 13 March 2017.

Naomi Klein, “Naomi Klein’s Guide to Resisting Power,” interview with Andrea Kurland, huck, 11 September 2017.

CHF ARCHIVE: “Ernest Green: Civil Rights,” America | Chicago Humanities Festival 2012.

CHF ARCHIVE: “Alicia Garza: Black Lives Matter,” Style | Chicago Humanities Festival, Spring 2016.

CHF ARCHIVE: “Covering #MeToo: Panel with NYT Reporter Emily Steel,” Graphic! | Chicago Humanities Festival, Spring 2018.

WEEK TWO: QUESTIONING & RETHINKING PROTEST

South Bend Voice | CC BY-SA

“When citizens of nominally democratic governments protest in the streets they are performing the foundational myth of democracy: the faith that the people possess ultimate sovereignty over their governments.

[T]he people’s sovereignty is dead and every protest is a hopeless struggle to revive the corpse. [...] If activism is to stay relevant, we must apply our techniques of protest to either winning wars or winning elections.” —Micah White, co-creator of Occupy Wall Street

Angela Davis, Women, Race & Class (1981). And “Freedom is a Constant Struggle: Continuities and Closures,” Birbeck Annual Law Lecture, 25 October 2013.

Walter Benn Michaels, “Against Diversity,” New Left Review, July-August 2008.

Slavoj Zizek, “Resistance is Surrender,” London Review of Books, 15 November 2007.

Mark Fisher, “Exiting the Vampire Castle,” openDemocracy, 24 November 2013.

Kimberlé Crenshaw, “Why Intersectionality Can’t Wait,” The Washington Post, 24 September 2015.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr., “Black America and the Class Divide,” The New York Times, 1 Feb 2016.

Eric Liu, “Protest Is Necessary, but Insufficient,” interview with Clare Foran, The Atlantic, 28 March 2017.

Nathan Heller, “Is There Any Point to Protesting?” The New Yorker, 21 August 2017.

Jedediah Purdy, “Environmentalism Was Once a Social Justice Movement,” The Atlantic, 7 December 2016.

Micah White, “Occupy and Black Lives Matter failed. We can either win wars or win elections,” The Guardian: Opinion, 28 August 2017.

Sarah Schulman, “When Protest Movements Became Brands,” The New York Times, 18 April 2018.

L.A. Kauffmann, “Dear Resistance: Marching Is Not Enough,” The Guardian, 3 July 2018.

CHF Archive: “The New Face of Global Activism,” Journeys | Chicago Humanities Festival 2014.

WEEK THREE: SOCIAL MOVEMENTS IN THE ERA OF SOCIAL MEDIA

Sherif9282 | CC BY-SA

“Social media has become a powerful way to express dissent, to disrupt and to organize. Digital activism, however, comes at a high price: The very tools we use for our cause can be – and have been – used to undermine us.” —Manal Al-Sharif, Saudi women’s right activist

Kevin Lewis, Kurt Gray and Jens Meierhenrich, “The Structure of Online Activism,” Sociological Science, Volume 1 (February 2014).

Erica Chenoweth, “Why Social Media Isn’t the Revolutionary Tool It Appears to Be,” The Washington Post, 23 November 2016.

Emily Parker and Charlton Mcilwain, “#BlackLivesMatter and the Power and Limits of Social Media,” Medium, 2 December 2016.

“Activism in the Social Media Age,” A Report by the Pew Research Center, 11 July 2018.

Manal Al-Sharif, “The Dangers of Digital Activism,” The New York Times, 16 September 2018.

Zeynep Tufekci, “How Social Media Took Us from Tahrir Square to Donald Trump,” MIT Technology Review, 14 August 2018. And, “Online Social Change: Easy to Organize, Hard to Win,” TEDGlobal 2014.

CHF ARCHIVE: “Arab Democracy & Social Media with Ethan Zuckerman,” and “Digital Democracy and Arab Spring: A Panel Discussion,” tech•knowledge | Chicago Humanities Festival 2011.

CHF ARCHIVE: “#justice: Using Technology to Create Social Change,” Citizens | Chicago Humanities Festival 2015.

CHF ARCHIVE: Siva Vaidhyanathan “Belief in the Age of Social Media,” Belief | Chicago Humanities Festival, Fall 2017.

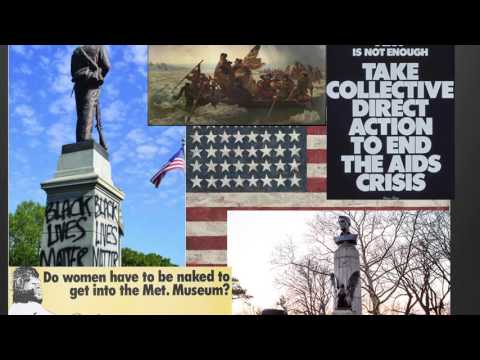

WEEK 4: THE POWER OF PROTEST ART AND LITERATURE

Nate Burgos | CC BY-ND

“Poetry is not only a dream and a vision; it is the skeleton architecture of our lives. It lays the foundations for a future of change, a bridge across our fears of what has never been before.” —Audre Lorde, black feminist poet

James Baldwin, “Everybody’s Protest Novel,” Partisan Review, 16 June 1949.

Audre Lorde, “Poetry Is Not a Luxury,” Sister Outsider (1984).

Boris Groys, “On Art Activism,” e-flux, June 2014.

“Picturing Dissent: 50 Years of Protest Photography,” aperture, 19 January 2017.

Alex Clark, “Writer’s Unite! The Return of the Protest Novel,” Guardian Books, 11 March 2017.

Bridgette Henwood, “The History of American Protest Music, from ‘Yankee Doodle’ to Kendrick Lamar,” Vox, 22 May 2017.

Sarah Schulman, “When Protest Movements Became Brands,” The New York Times, 18 April 2018.

Spencer Kornhaber, “Can Protest Art Get its Mojo Back?” The Atlantic, June 2018.

T.V. Reed, The Art of Protest: Culture and Activism from the Civil Rights Movement to the Present (2019).

“Vision & Justice: A Civic Curriculum,” edited by Sarah Lewis, Aperture, 25 April 2019.

CHF ARCHIVE: “Politics in American Art with Wendy Bellion,” Citizen | Chicago Humanities Festival 2015.

CHF ARCHIVE: “Artists as Activists,” Citizen | Chicago Humanities Festival 2015.

Syllabus curated by Alicia Williamson, a writer, editor and independent scholar who works on US radical literature, feminist theory and working-class studies. A long-time activist, she has participated in multiple campaigns related to economic justice and served as a community organizer for a grassroots public transportation advocacy group. She holds a PhD in Critical and Cultural Studies from the University of Pittsburgh where she taught in the Literature, Writing and Women’s Studies Programs.

Become a Member

Being a member of the Chicago Humanities Festival is especially meaningful during this unprecedented and challenging time. Your support keeps CHF alive as we adapt to our new digital format, and ensures our programming is free, accessible, and open to anyone online.

Make a Donation

Member and donor support drives 100% of our free digital programming. These inspiring and vital conversations are possible because of people like you. Thank you!