Life Advice from Your Film Dads: Harold Ramis (2009), John Waters (2022)

S2E5: Life Advice from Your Film Dads: Harold Ramis (2009), John Waters (2022)

Apple Podcasts • Spotify • Pandora • Overcast • Pocket Casts

We’re giving you a well-rounded comedy education today with talks from two famous/infamous American film directors: Harold Ramis on the AFI 100 Funniest American Movies and John Waters on a career from trashy b-movies to Criterion approved trashy b-movies.

Read the Transcript

[Theme music plays]

HAROLD RAMIS: Making films easy, being in a close, intimate relationship with someone over a long period of time, that's really tough.

JOHN WATERS: If he had been alive to see that the National Registry named that as a great American film this year. Even I'm appalled at that.

[Cassette player clicks open]

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Hey what’s going on - thanks for tuning into Chicago Humanities Tapes - the audio arm of the live Chicago Humanities Spring and Fall Festivals. Twice a year, we pack our calendars with the best speakers from across the arts, technology, literature and politics - people like Rachel Maddow, Bob Odenkirk, Michio Kaku - all giving you expert insights on what’s affecting our lives. Head to chicagohumanities.org for more info and to see if any of your favorite speakers are currently in town.

I’m Alisa Rosenthal, and I’m on a quest to dig through our thirty plus year archive to find the answers to humanity's biggest questions. Today: what can we learn about life from comedies? Here are two glass-half-full kinda guys breaking down their careers and sharing behind-the-scenes stories along the way.

We’re really straddling the comedy history spectrum today, giving you a well-rounded comedy education from two titans of directing - Harold Ramis who knows subversion and John Waters who is subversion.

So speaking of, the only content warnings I have for you is that Harold Ramis is so wholesome it might just make you unexpectedly cry on your commute, and the John Waters program in the second half is one of the crassest things I’ve ever heard, and that’s even with trying to condense it a bit for you. So - we’ve got some high brow and some low brow for you today - that’s comedy, baby!

Up first, Harold Ramis - you know him as Egon from Ghostbusters which he also co-wrote, and the director of such blockbusters as Caddyshack, Stripes, and one of my favorite movies, Groundhog Day. And one of my favorite movies, Groundhog Day.

Born in Chicago (and like, actually Chicago! Go Senn High School Bulldogs!), he couldn’t be more beloved in the Chicago community. The Second City originally named their comedy film program the Harold Ramis Film School in his honor.

The former joke editor at Playboy, he then moved on to writing and performing for the National Lampoon Radio Hour, SCTV, co-wrote Animal House, and the rest is history.

As Barack Obama said of him, “When we watched his movies … we didn't just laugh until it hurt. We questioned authority. We identified with the outsider. We rooted for the underdog. And through it all, we never lost our faith in happy endings.”

We unfortunately lost Ramis in 2014 to complications from an autoimmune disease at just the age of 69. We’re so lucky to have this comic lecture from 2009 of his favorite funny moments in film to get inside his comedic genius head, and get to know him more as the big film-loving kid he always was.

[Theme music plays]

[Audience applause]

HAROLD RAMIS: Alright, that’s good enough, thank you. I have here a list of the 100 funniest movies of the last 100 years from AFI, and as Avi said I have 4% of those movies.

I'm thinking back to 1944 when I was born, and I'm old enough to remember a time before television. When the family sat around, actually listened to radio. And I was around for the real beginnings of television when all of America watched the same shows. And most of everyone's favorite shows were the comedies Milton Berle and Jackie Gleason and Sid Caesar and The Show of Shows, later The Steve Allen Show, I Love Lucy, all that stuff kind of entered the American consciousness, and mostly it was extensions of vaudeville and older theatrical forms. Ernie Kovacs came along and started doing some real original kind of surreal television. But for me, what was really engrossing in television were the movies that were recycled on TV. Hollywood and TV were at war. Hollywood would not license contemporary films to television, so all television could do is recycle really old stuff. So if you were a kid watching TV in the fifties, you saw all of silent comedy from Chaplin to Mack Sennett, the Keystone Cops, Laurel and Hardy, Harold Lloyd, Buster Keaton. That was what I grew up on. So being the son of the grandson of immigrants, Jewish immigrants and working class and, you know, lower middle class, middle, middle class, on a good day, I kind of really I identified most strongly with the Marx Brothers. My father had a very dry kind of Groucho Marx sense of humor. His brothers weren't funny, but. They were kind of my comic ideals, and those were the movies that really made me laugh the most.

Coconuts, Monkey Business, Animal Crackers, Duck Soup, Horse Feathers, Day at the Races, Night at the Opera with anarchy and the triumph of the common man over the pretensions and prejudices of the ruling power elite, The Marx Brothers, Groucho, Chico, Harpo and Carl. That's what I got, huh? That's what I got from the Marx Brothers. It was a great lesson in comedy and an actual political point of view. I also love the screwball comedies of Howard Hawks, Bringing up Baby, Girl Friday. Other films like The Thin Man, My Man, Godfrey, Ninotchka, The Philadelphia Story, and of course, Frank Capra's Feel Good films, Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, and It's a Wonderful Life, of course. But Capra also could do screwball comedy. It Happened One Night is a classic, and one of my favorites was Arsenic and Old Lace. I loved Cary Grant. My my great movie heroes were Cary Grant and Errol Flynn. I wanted to be both, and I also wanted to be Groucho and Harpo. So those were my kind of role models. My father was way too lazy to be any kind of role model. He just sat in the chair, tossed off one liners and kind of laughed. But these were screwball comedies, fast talking, witty and sophisticated, great writing, wonderful acting.

Film comedy in the fifties for me was Jerry Lewis and Danny Kaye. And then as we got toward the sixties, Billy great Billy Wilder comedies, Some Like It Hot and The Apartment. On TV, Dobie Gillis, in print, Max Shulman and Mad Magazine. And then I went to college, in '62. '62 was a kind of watershed year to be going to college. I told people when I went away to college, I looked like John Kennedy. By the end of college, I looked like John Lennon. I had politics like Nikolai Lennon. But after the after the Cuban Missile Crisis in '62 and then the Kennedy assassination, comedy was a little hard to come by through the mid-sixties. But a couple of Sid Caesar's writers were keeping it alive. And by my senior year, I discovered Carl Reiner and Mel Brooks, 2000 Year Old Man and almost everyone I know in comedy who grew up at that time listened to this material. I've worked with Billy Crystal a couple of times. He can quote any line from Carl Reiner and Mel Brooks. Same with Paul Reiser. We did a pilot for CBS and Paul, he and I would all day we would just trade Mel Brooks lines.

I started acting in college, serious acting and always has been performing. I started performing music when I was 13 years old, playing the guitar and singing. I went to the old Town School of Folk Music starting in 1960 and did skits and shows musical skits and shows. In college I was in my first serious play, Oedipus Rex. I was cast as the priest of Zeus. I opened the play with a two and a half minute speech then disappeared. Did not appear in the rest of the play. So but I stayed in makeup and costume for the rest of the play so I could take a bow at the end two and a half hours later. But we rehearsed the we rehearsed the play a lot. We had a dress rehearsal and there was no curtain. There was it was a proscenium stage, but it was a they had built the stage in levels. There were stairways leading up to the temple of Zeus, and at the beginning of the play, the lights would come up and I'd be kneeling at the at the doors of the temple and then turn and give my speech. Well, opening night came and they called places. Lights went out, and I realized something was terribly different. We had always rehearsed the play with a light on so we could find our places on stage. On opening night, there were no lights. It was pitch black. So in the dark you could hear the actors stumbling out on stage, like tripping over the scenery, clunk, clunk, clunk. And I thought, Oh my God, I've got to find my spot in the dark. So I was careful not to fall. I've worked my way up. I got to the top level. I got down on my knees, felt the wall, got down my knees and prayed that I was in front of the doors where I was supposed to be. The lights came up and I was not. I was I was facing a blank wall about five feet from where I was supposed to be. So on my knees I started shuffling across the way I was supposed to be.

While Carl and Mel were pursuing their insane Yiddish sensibility in the late fifties and early sixties. Something was happening at the University of Chicago that really would change American comedy forever. Mike Nichols and Elaine May, The Compass and the Second City as an extension of The Compass, they were exploring things that had not really been talked about in American comedy. There was a heavy Freudian kind of influence. Existentialism was the the key word. The coffeehouse and sensibility, the Beat Generation finally found a comic voice. And when I first heard Mike Nichols, Elaine May, I thought, Yeah, that's that's good. That's something I would like to emulate somehow.

Meanwhile, in England, another school of comedy was developing. First it was Peter Sellers and Spike Milligan. They did The Goon Show in England. They had a big influence on what became The Establishment. I forgot if they were at Oxford or Cambridge. But it was Peter Cook and Dudley Moore and Alan Bennett and Jonathan Miller, and they were doing a kind of British form of what was happening at the Compass and Second City and with a different cultural flavor. But they shared something which Bernie Sahlins always expressed to me, as always work from the top of your intelligence. And he always mentioned, let's raise the level of reference.

The British comedies, the fifties and sixties were very appealing to me. It was always Peter Sellers and Alec Guinness and Alastair Sim. Kind Hearts and Coronets, Lady Killers, Man in the Cockpit, Lavender Hill Mob, Green Man, Man in the White Suit, Captains Paradise, I'm Alright Jack. And then, all right, Sellers finally teamed up with Terry Southern. Writer Terry Southern and the director Stanley Kubrick, made one of the great comedies of all time. Dr. Strangelove. Sellers, of course, plays three parts in the movie.

Anyways so Peter Sellers was kind of really great and the first person to really break out of out of the British, the new British comedy tradition. But then I started hearing about Peter Cook and Dudley Moore. They had a popular show on the BBC, not only but also and then the stage shows Beyond the Fringe and the sequel to that Behind the Fridge.

And British comedy was very smart. It just seemed so smart. I had been an editor at Playboy magazine, and when I went to London for the first time in 1971, and I was told to look up Victor Lownes, who was a Playboy executive, ran the European operation for Playboy. I went to his house in Connaught Square, which was known as kind of the London Playboy mansion. And Victor knew I was had done a little Second City before I got there. And he said, What do you think of Monty Python? And I said, Who? Who's Monty Python? He said, It's not a person, it's a group. So when I got back to the States after Victor had told me about Monty Python, PBS started licensing the BBC shows Monty Python's Flying Circus. I always think of Monty Python as the first postmodern comedy because they drew from everything from every period in history. Their costume pieces are great. It's very literate. It's very silly. It's physically funny, it's witty, it's, it had it all for me. And it kind of raised the bar a little bit, I thought.

Now my own work, for me pales by comparison. But a lot of my early stuff was pretty well-received. So I brought something from Caddyshack. Caddyshack was my. It wasn't intended this way. It starting out started out as a coming of age story where going can tell the story of a young caddy in the process hired Chevy Chase and Rodney Dangerfield and Billy Murray and ended up there was a kind of an incredible magnetism to those characters. And the movie shifted away from the ingenue story and really ended up being their film. And I realized as I was doing it, it's like a Marx Brothers movie. Rodney is like Groucho, Bill is like Harpo, Chevy's the Chico of the in that formula. And Ted Knight was like this Sig Ruman, this stuffy upper class guy. And so I went with that and thought, All right, the ingenue story in those Marx Brothers films, it hardly mattered. It was nice. The young couple gets together at the end. Fine. No one really cared they were just there to see the Marx Brothers. And in Caddyshack, it's Rodney, Bill and Chevy that steal the film. So here's one of Bill's classic scenes written by Brian Doyle, Murray and me, embellished by Bill.

Many years later, my wife for her 50th birthday, she'd had a lot of connection to Buddhism. My my mother in law had lived for over 30 years in a Buddhist meditation center. My wife spent four college years in a Buddhist meditation center. So for her 50th birthday, she said, I want to meet the Dalai Lama. So we had some friends in Glencoe who knew His Holiness. They said, Oh yeah, that can be arranged. We went to Washington, D.C., We went to a big public talk. We went to a smaller private dinner, and in the afternoon our friends said, All right, His Holiness can see you for a couple of minutes maybe. You know, he's got to go, to, up to Capitol Hill to speak to Congress. So we went into his suite at the Four Seasons, of course, and his appointed scheduling secretary was like, really nervous. You know, you got to get up there and Sierra Club's waiting and congressmen are waiting. And the Dalai Lama, he looked at us, said, "Sit down, please." So we sat down with him. We talked for a few minutes. I told them I was a filmmaker. Then he dropped Richard Gere's name on me. He said, "As I said to Richard Gere, you have a great opportunity to speak to people about compassion." All right, great. So a couple more years go by, The Dalai Lama came to Chicago. My wife and I were asked to executive produce the the stage performance that preceded his appearance and set the stage for him. We we designed the backdrop, the painted backdrops and great experience. Again, we got to meet with him at the Palmer House. But this time the Buddhists were high level monks and parts of his entourage were coming up to me saying, "What is Caddyshack?" And I'd, "Oh- Caddyshack's a golf movie," and they said, "The Dalai Lama is talked about in this movie?" I said, "Yes, he is kind of, you know." I guess he hasn't seen it, you know. And they were interested. But I said, "Did the Dalai Lama watch movies?" I wasn't going to send them Caddyshack of course. I thought maybe he'd seen Groundhog Day because all the Buddhists really had embraced Groundhog Day. They didn't know His Holiness likes nature films. His last film he saw was March of the Penguins. And. All right, he's not going to be watching Meatballs, I thought. I did a kind of screwball comedy farce. I'm going with my lesser known film. Multiplicity was a film that was very well-received by people who saw it, nicely reviewed, did no business because it came out and was crushed by big summer blockbusters like Independence Day. But in it, Michael Keaton is a man who is finding he has no time for himself. His life is really taken up by his work, by his wife, by his family. No time left for him. He responds to a cryptic advertisement. He gets a clone, which he sends to work so he can spend more time with the wife and kids.

I had after Groundhog Day that bought me a few more years of credibility in Hollywood, but I moved to Chicago 13 years ago, and my promise to my family was that I wouldn't immediately abandon them and run off to L.A. to make a movie. But I got a call from my agent who said, Billy Crystal is going to make a movie about a psychiatrist who starts treating a mob boss, and we'd like you to direct it. And I said, Who's going to play the mob boss? And I said, It doesn't matter. We'll get somebody. And I don't think so. You know, if it was just Billy and it was it read very broad, it was like a bad kind of parody of The Godfather. And I thought, No, I'll pass. And then my agent called back a week later, said, What if it was Robert De Niro? I said, All right, but I've made a promise to my family. Will Robert De Niro and Billy Crystal shoot the movie in Chicago? Next day, my agent calls back. No, they'll only do it in New York. I said, I pass. And I was like, kicking myself. But I do honor my my family. So they hired another director. Months went by. That director did a draft of the script. Bob hated it. So I got the call and they said, Are you ready to leave Chicago? The appropriate time had gone by and met with De Niro. I made it. I did some very thorough research on the history of organized crime and Italian mafia and on the psychology of his character. I had notes on one little script card. I talked to him about four things: anxiety, guilt, rage and uh anxiety, guilt rage. Yeah, that was several years ago. I'll get the other one. What's the other thing we all suffer from? If anyone comes up with my. Depression. Yes. Thank you. Grief. Yes, grief. So I rewrote the script with Peter Tolan and had a wonderful experience making this film. I don't know what it is about comedy but so many comedians and comic filmmakers that want to be taken seriously. And when they do, it's way over the top. Maybe the people who do comedy really are angry, depressed and really miserable. I don't know. I'm not.

The psychiatrist Viktor Frankl, who wrote the wonderful book Man's Search for Meaning. He survived the camps in World War Two, and his part of his analysis of psychiatry is that Freud imagined that we're driven by a will to pleasure. Everything we do is about avoiding pain and seeking pleasure. And then Adler came along and said, No, we're driven by the will to power. And Frankl tops that and says, No, it's really we're driven by the will to meaning. And that's the arc of my career. I started entertaining. I'm sorry. In order to get laid. Look, there it is. The will to pleasure. I wanted all the pleasures that that life had to offer. And then my early films were successful, and I experienced the pleasures of money and fame, which is the will to power. Now, having been through all that, without either causing any serious permanent brain damage or having really achieved any greater comfort than I had when I started, meaning is all that's really left to me. But if Kirkegaard and Sartre and Camus are right, life is unfortunately essentially meaningless. So where do you go from there? I guess there's a character, I'll be going to Spiaggia, but. But anyway, there's there's a character in my my remake of Bedazzled, played by Brendan Fraser, who's the most erudite, sophisticated author in the world. And he says to a woman who's fascinated by him when she mentions existentialism, he says, "Every time I reread Camus and Sartre, I will say to myself, 'Why does the existential dilemma have to be so damn bleak?' Yes, we're alone in the universe. Life is meaningless and death is inevitable. But is that necessarily so depressing? It just puts the burden on us to fill our lives with joy and wonder and weirdness and adventure. Whatever it is that makes your heart pound your mind expand and your spirit soar."

[Audience applause]

HAROLD RAMIS: Well maybe we've got time for one or two questions.

AUDIENCE MEMBER 1: What's your favorite film?

HAROLD RAMIS: My favorite film of mine or of anyone else's. Now I've got about 200 favorite films. I can't. I can't do favorites. My making films has been like the greatest, a tremendous opportunity and a really great pleasure for me and my worst day as a director, it's been great. So, I mean, those are what I consider high class problems. It's just a real privilege and I like them all. There are things that really misfire in a lot of my films. They're not at all what I intended, but they all have they all have great things. And I see in them what I was going for. And to some extent, they're all for me, successful in some way.

AUDIENCE MEMBER 2: Hi. And what's your fantasy project that you haven't done yet in this quest for meaning? What's next? If you could do anything you wanted to do?

HAROLD RAMIS: If I could do anything in my quest for meaning, it would be to uh, this sounds sappy. Get through my life with a really successful marriage. We're still good, you know, 25 years. But it is marriage is tough. It's where you play out all your all your problems are played out in that dynamic relationship with another person. Making films easy, being in a close, intimate relationship with someone over a long period of time, that's really tough. Someone asked the Dalai Lama, What do you do if you're married to an essentially negative person? The Dalai Lama laughed and said, Wow. He said, I'm not married. He said that, you know, with your neighbor, it's easy. You say hello, you walk by, you see him a couple of times a week, someone you live with, you know, you're on your own.

All right. So are there a couple of actors or actresses that I really admire? There's so many that I admire, and we would all probably make the same list. The amazing thing to me is how much talent there is and how little really superior work happens as a result of it. Film schools churn out really good people on the technical side, great designers, great cameramen, acting schools, wonderful actors, writers. They're not dumb. There are a lot of really smart people writing films and television, but it's so hard to get it all together. So my I always say there are more well-made films than good films. And when when they are good, I just really want to celebrate those things.

AUDIENCE MEMBER 3: How did you end up working with people like Bill Murray and that whole crew from Chicago through Second City or from living in Chicago originally? Or is that how you got connected to who are now really famous actors.

HAROLD RAMIS: Yeah. Second City was really where we all got together. I would started working in Second City in late '68 and the touring company got on the main stage in '69. And in in that early company was Brian Doyle-Murray and one day Brian said, Hey, let's go up to Wilmette, have, you know, my mom wants to make dinner for us. You'll meet my family. I went up there and he said, Let's stop off and pick up my brother Bill, who's working. And Bill was running the concession stand on the ninth hole at the Wilmette Public Golf Course. He had just graduated from Loyola Academy. He was very funny. I saw him again, I think that winter at the Treasure Island across the street from Second City on Wells Street, he was selling hot chestnuts on the street. Funniest chestnut salesman you'll ever see. And then next time I came back to Chicago, I was traveling a lot in those days. I came back and he was in the company at Second City and already a powerful comic force and a very disruptive force. And then at that time, when I'd been working with John Belushi, John had gone off to work at the National Lampoon. John, I also met at Second City. We worked together there. He brought a bunch of people to New York to work at the National Lampoon. He brought Gilda Radner and Bill Murray and me and Brian and Joe Flaherty, and we became the Lampoon Company. So we all had this this history going. And then Lampoon wanted to make a film. I started writing the Animal House, and that got made with Belushi, although we had written parts for Bill and also Dan Aykroyd, the studio didn't want them at that point. And then Ivan Reitman kind of brought Bill and I together in movies. First, I got the first I used him in Caddyshack, and then I wrote on Meatballs, which he was in. And then we co-starred and I co-wrote Stripes and then, uh, and then the Ghostbusters, of course, and Groundhog Day. We did six films together, but we were a kind of a comedy mafia, not unlike the Judd Apatow crowd that's working now.

HAROLD RAMIS: So basically. Pardon?

AUDIENCE MEMBER 3: You gave Bill Murray his start basically?

HAROLD RAMIS: Well, he gave me my start in a sense. I say this to film students all the time. Now identify the most talented person in the room, and if it's not, you go stand next to them. So thank you very much.

[Audience applause]

[Theme music plays]

ALISA ROSENTHAL: That was Harold Ramis recorded live in 2009 as part of the Chicago Humanities Fall Festival on the theme of laughter.

We’re going to really switch gears here, so tap into that part of yourself that really loves poop jokes. Director, writer, and Baltimore native John Waters is best known for the film and subsequent Broadway musical Hairspray - and then subsequent movie musical. His ‘70s films Pink Flamingos and Female Trouble with drag queen Divine brought queer voices in comedy to the forefront with a lot of filth and cashmere sweaters.

He just a few months ago received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Interviewed live in 2022 by writer, musician, and filmmaker Richard Knight, Jr. - author of, appropriately, the book Haunted Houses, Porn Stars and Toy Collectors: My Encounters with Remarkable Places, People and Things, here Waters is in conversation about his debut novel Liarmouth: A Feel-Bad Romance.

[Theme music plays]

[Audience applause]

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: John Waters is here in the flesh.

JOHN WATERS: Thank you. Live like that place outside the L.A. airport that used to say live- no, nude live girls. That was the thing. That's nice, we're compared to dead ones, anyway, hi.

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: I thought that we should start with a trigger warning.

JOHN WATERS: I never understood them either. I thought you went to college to have your values questioned.

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: Okay, so trigger warning. John Waters, novelist.

JOHN WATERS: Thank you. Thank you.

[Audience applause]

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: So can you just give us a quick little synopsis? Of the book.

JOHN WATERS: Sure. I give you the trailer. It's Marsha Sprinkle, suitcase thief. Her family wants her dead. She hates animals and children hate her. She's on the run with a big chip on her shoulders. She's dangerous. She's depraved. And they call her liar mouth until one insane man makes her tell the truth. I can't help her. It's a feel bad romance.

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: Where did Marsha Sprinkle come from?

JOHN WATERS: I don't know, I just wanted to think of somebody that would be friends with Serial Mom and Dawn Davenport and Francine Fishpaw and all the heroines of all my movies I think she'd get along with them.

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: She's like Dawn Davenport's stepsister.

JOHN WATERS: I just wanted to make a character that would be totally dislikable to the rest of the world. But have the readers secretly like her. Yeah. Which is all my movies, in a way.

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: There is another running theme throughout all of your work in the background. When I when I hear you interview and read things about you. Tomorrow's Mother's Day.

JOHN WATERS: Yeah. Domineering mothers day for gay people. Freud would say that. And absent Fathers Day.

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: And anybody who has not heard your commentary on Mommie Dearest needs to get that DVD tomorrow.

JOHN WATERS: Well, I think that if they cut two scenes out of Mommie Dearest, she would have won the Oscar. If she hadn't had the "it's not you, the dirt I hate" and the coat hanger scene, which is so over the top. The rest of it was good. But Frank Perry made that film. I mean, it is a good movie technically, although later, you know, I was always on Joan's side - later - because her daughter was so serious about it and everything and she was so abused. But later she was at the Castro Theater with drag queens dressed as her mother doing a show. So how upset was she, really?

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: She cashed in. Absolutely, sure.

JOHN WATERS: She's cashing in on it. No more wire hangers, you know. Come on.

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: So in the background again, and you've acknowledged this several times, your own mother, okay, took you to, you know, see wrecked cars.

JOHN WATERS: Yeah.

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: Let you do those crazy puppets. I mean, when you did Pink Flamingos, she was making fliers and sending them to you.

JOHN WATERS: She was understanding, but horrified by the movie. My mother was Serial Mom more. I mean, she's the one that taught me the rules of good taste. And I'm glad she did. Because if I didn't know the rules, I couldn't have defied them.

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: So your mother was very supportive -

JOHN WATERS: She was horrified but supportive.

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: Horrified but supportive. What about coming out?

JOHN WATERS: Well I never came out. That seemed to me like so like, a bar mitzvah or something, you know? My mother never asked if I was gay because she thought the answer would be worse. So they I mean, I figured, what do they think I was, you know. But I had girlfriends too, which confused them. And I also had straight friends that were we hung around with all different kind of people. I still like that I'm not a separatist. I don't get why people want to hang around with themself. I don't want to get why people fuck people that look like themselves. I mean, otherwise Steve Buscemi and I would be married. But so she was confused. She didn't know what because I always said gay is not enough either. It's a good start. But so and the first time I ever went in a gay bar, I thought I might be queer, but I'm not this. This was so square. So, she was confused, you know, by everything. And still at the end of my last movie, A Dirty Shame, she said, Oh, God, what's this one about? And I said, "Sex addicts", and she said, Oh, "maybe we'll die first." So I got my humor from her too, I think. Yeah, my dad just said, "It was funny. Hope I never see it again." And my dad lent me the money for those early movie. Never saw them, and I paid them back with interest.

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: Now that is love.

JOHN WATERS: He was stupefied. Stupefied.

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: Have gave you the money for Pink Flamingos. Wow.

JOHN WATERS: Yeah it was. Yeah. I wish he had been alive to see that the National Registry named that as a great American film this year. Even I'm appalled at that. Yeah. No, it's really lovely. It's really nice. And Criterion's putting out this beautiful version over the next couple of months.

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: Next month, the 50th anniversary.

JOHN WATERS: Really great wait til you see the extras. We go back in the houses and tell the people that live there what happened in their house.

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: I mean, we've gone from this fringe person who scares the mainstream to the national registry. You're this beloved figure.

JOHN WATERS: AndI'm the same, though.

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: I mean, has the culture just caught up to you?

JOHN WATERS: Yeah. People's sense of humor got more twisted and they learned that laughter is how you get people to listen. But the main thing you have to do is make fun of yourself first.

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: Let's get back to the book for a minute, because this is a huge undertaking. Your first novel.

JOHN WATERS: This took three years.

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: This is an endeavor. Can you just talk about the nuts and bolts? Do you have a favorite room?

JOHN WATERS: Yeah, I have one room. I go in, I go in every day at exactly 8 a.m.. I get up at six, I drink five cups of tea. I read about 100 newspapers online and I get them delivered. I look at my emails and then everybody knows never to call me in the morning. I don't look at emails, I don't answer the phone. I write from about 8 to 11 every day, Monday to Friday. And after, you know, I think up fucked up things in the morning and sell them in the afternoon. And I've been doing that for 50 years and I handwrite everything with Bic pens, the same kind of legal pads. I have to have Scotch tape. I cut it. And when I have a first draft, which takes a long time, my assistants can read my writing and they type it and then I cut that up. It's half written, and when I turn it in, it's about sixth draft, I think, and the first drafts the hardest. You just keep going. Don't endlessly rework the first chapter. I mean, at the end of the day, read it. But, but the next day just keep going. And when you're finished, you usually read the whole book and you maybe hate it, which I did. But you think, who wrote this? But it's a lot easier to rewrite the second draft than it is to write the first one. And each time you write, it gets better and better, hopefully. And if you cut something out and change it and then you put it back in, usually you're done.

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: Do you do an outline to start with or you just.

JOHN WATERS: Well, I get a deal. You know, I'm used to pitching movies and pitching books. I mean, to get a book deal, I, I think up the plot. Yeah. Before I go to the publisher and it gets less and less sometimes I can get a deal with a paragraph if it's good. But I go in and yeah, I give them the whole- First I think of all the characters. I think of what genre I'm parodying kind of, and then I think of the characters. And then I, one critic that hated me in the old days said my- then I think up the plot, which she'd call "just a clothesline to hang my filthy wash." Which is true. And uh, and so then I do the plot and I always do three acts. I'm still like three acts from 16 millimeter, 30, 30, 30 minutes. And then I start, but it changes many, many times. This was based on a movie idea from a long, long time ago that I really never developed. I never pitched it or anything. It was just, but Marsha did steal suitcases in airports and she did have a boyfriend that was her fake chauffeur. That basically, his salary is he could have sex with her once a year and this was the day he was collect. But as she puts it, she's no man's used up calendar. So I had some ideas. Yeah. But then other characters that were in it, sometimes I have other projects. I stole some of them for Carsick when I did the pictures, part of the rides I imagined that were the worst rides and the best like I can. You know, I don't let things go to waste. I don't have any old things that haven't been plucked clean of ideas that I didn't work and put into something else and developed.

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: You're a renowned bibliophile with over 8000 books.

JOHN WATERS: And I got more than that.

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: Then more probably probably many more since that that quote. You once said, if you go home with somebody and they don't have books, don't fuck them.

JOHN WATERS: Well, I have to say, though, if they're cute enough I have violated that rule. And the other thing is even worse, if you go home with somebody and they have books in the bathroom, don't fuck them. Especially a bin of jokes in the john and old US magazines.

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: Okay. So of the 8000 plus some of your favorites.

JOHN WATERS: Well, I think I wrote in one of my books, Role Models, I think my favorite writer, I love Denton Welch. I love Jane Bowles Two Serious Ladies is my favorite novel. Ever, ever, ever in the whole world.

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: Boy, they're fun.

JOHN WATERS: Oh, they're hilarious. That book is so funny in parts of it. I like Ivy Compton-Burnette. I like, I love Denton Welch really a lot. I wrote the introduction to Tennessee Williams Memoirs when it was re-released. He gave me the freedom to get out of suburbia and know what Bohemia was and everything. So he was a huge influence on me. Edward Albee, The Theater of the Ridiculous. Jean Genet, oh God. I used to read him in Catholic school, and they were so dumb. They didn't know but thought, he's reading, good. Oh, if they only knew Our Lady of the Flowers was not what they were teaching us. Right. Grove Press saved my life. Right. So I always read books that were, I don't know, I read William Burroughs, Genet, all the beats who were-

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: Who called you The Pope of Trash?

JOHN WATERS: William Burroughs called me The Pope of Trash. That was like I was being anointed from God above, right. And I even opened for William one night. We worked together because he was very smartly reinvented for the punk world by James Grauerholz, his friend. And he gave readings in all the punk clubs and stuff. And I went to William's house before and I sneak looked in his bedroom and he had a single cot. And he was reading the paperback version of the Guyana massacre. And he served warm vodka in an empty peanut butter jar. It was great. It was so great. I loved him. And this is a parody of many things. It's a parody of noir, definitely, in some ways. It's a parody of narrative. Not so much stuff happens in four days that all characters would drop dead. It's ridiculous how much could've happened. I love ridiculous alliteration I use. I love to have ludicrous sex writing. I have parody, I think experimental writing where I just talk to the reader for suddenly for no reason in the middle of the book. So, I know from Broadway, one thing I really learned from doing Hairspray on Broadway, something I had never done, and I didn't produce it or write it, but I was there constantly like a studio executive. So I saw the endless fiddling they do with it before it's, quote, frozen before it opens. And you can get not one laugh and they change the pause or two words and the whole house is roaring. It's amazing to see how close it can be about timing and the way you say something and the way you do it. And, you know, I'm trying to make fun of political correctness, but at the same way I went through the book with my editor, my agent, the three generations of women that worked for me to say, what can you do today with humor on the edge? It's easy to be offensive, but I'm not trying to do that. I'm trying to make fun of the rules that I live in with that you all live and that my audience lives in.

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: I mean, this humor, which makes the transgressive go down easier. There's also always this very deep affection. You love these people.

JOHN WATERS: I do. Even the most damaged people I find appealing. And I try to. That's why I don't like people that judge other people. So I'm just asking you not to judge people til you know the whole story. And sometimes I'm trying to give you the whole story as ludicrously, so terrible. But at the same time, I'm trying to make you laugh at things that you might fear or what is terrible sometimes if you. If it's not real, you can laugh with it. Hopefully. I'm always asking you to laugh with my character's not at them, I don't think. That's a big difference.

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: Which is probably one reason why everybody, you know, on the outside, as I said, I really you said once to RuPaul, you know, even among minorities, you're minorities. You said this earlier. I really do think of you as the outsider's outsider. And certainly in the climate we're in now, you know, you're like this huge hero to have lived your whole life in the in the early seventies. You're like this.

JOHN WATERS: I'm not in my early seventies. I'm in my late seventies.

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: No, I'm talking about the 1970s when Pink Flamingos and-

JOHN WATERS: Oh, yeah, okay.

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: No, no, no.

JOHN WATERS: I'm 76. That's middle aged. I'm not going to be 152. Old chicken's make good soup.

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: Absolutely. Okay.

JOHN WATERS: But still, it's amazing to me. I agree that kids come up to me, you know, and and they're so amazing. They weren't even born when I made some of these movies. And they keep my movies, keep getting put out and they're never rediscovered. They're not hard to see. They're I mean, Multiple Maniacs was on HBO Plus, how could that possibly be?

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: How could that be?

JOHN WATERS: You know, I don't know myself. And I think Criterion really, I, great salute to them. They put the class back in the art business because they they celebrate all kinds of movies. Well, not all kinds. They celebrate both ends and nothing in the middle, right? The very arty and the very trashy. But the ones that are so trashy, they're so extreme.

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: Okay, so talking just for a moment about movies. It's been over 15 years since The Dirty Shame, since you've made a movie, which is a fucking dirty shame.

JOHN WATERS: Well, I've been paid to write three other ones that never came out that were a sequel to Hairspray. Three different kinds for Hollywood. That was, they paid me very well and I did it. They never came out. And I have another one that I was paid to do called Fruitcake, which is a children's Christmas movie that might happen. Who knows? I can't say anything about it. It's just I can't. So who knows? Might, might, might, might. And so it's not that I haven't been active in Hollywood. They paid me to do things and Hollywood treated me fairly. I don't have any complaints about it. They treated me fairly. One thing you should know, you know, if you don't want them to tell you what to do, then make your film on a cell phone camera. If you want a house, you listen to what they have to say and that's how it works.

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: Well, we can you know, there's a sliver of hope that perhaps you'll do that. We have a couple of audience questions, and then we're going to open this up, some other questions. Okay. This is from Ty Eremando. Hello, John. I'm a huge fan of yours and an aspiring 17-year-old filmmaker that wants to make the same shocking, bizarre, quote, unquote, trash cinema that you have perfected. Anyways, my question, although quite cliche, is what advice would you give to young filmmakers like me who want to be unique and stand out among the thousands of films being made? Thanks.

JOHN WATERS: Well, the advice would be, to do what you want to do, is not imitate me. You have to do something that would surprise me, that would come out. And I always said to get an NC 17 rating with no sex or violence, what could that be? That's the key to that next shocker. Ideas that are so perverse that parents are just nervous of you thinking about them. What a great movie that would be. And also to tell all young people and no is free. Don't fear rejection ever. Or it's like hitchhiking. You need one person to say yes to back a movie. Don't borrow money from people. If you really don't think you can pay them back, it's not a grant.

RICHARD KNIGHT JR.: This is from Anonymous. What is your favorite memory of Divine?

JOHN WATERS.: My favorite memory of Divine would not be when we were filming. My favorite memory of Divine would be at Christmas, which he really loved. And I don't know, it just being with him. He was a great host. He loved to cook. He loved to have friends over. He was the opposite kind of the Divine image that you think of this scary person. Divine in high school got hassled constantly, and later he used that rage to become the character. But once he established that when he got the best reviews is when he played the opposite, when he played a loving mother or a drunken housewife or something. So my my favorite memories of Divine would be at Christmas. And I remember the last time I ever saw him Hairspray had opened. It was a hit. He got a great review of Pauline Kael. It got all great reviews and we had dinner at Odeon in New York, just the two of us, and we sat at that last table. We were glowing. It was great success. It just happened a week earlier. I kissed him goodbye, he got in a limo, which I'm sure he didn't pay for, and and he dropped dead the next week. So it was a great last night. But and today, you know, the graveyard he's in has many, many visitors. And so I have I'm going to be buried there. We're all being buried there. Mink Stole. So we call it Disgraceland. It's a whole, Pat Moran, Mink Stole, Dennis Dermody, a lot of us. We're all going to be buried there. So. And I like the idea of being buried with your friends, with your studio, you know. Not that many, no one does that. I don't know anyone that's buried with their friends, do you?

[Audience applause]

[Theme music plays]

ALISA ROSENTHAL: That was John Waters with Richard Knight, Jr. recorded live at the University of Illinois Chicago in Spring 2022. Head to the show notes at chicagohumanities.org for the links to the full videos of both this program and Harold Ramis, whose full video has film clips of all of his favorite comedy moments, as well as the link to check out John Waters’ book and some other fun photos and resources.

Chicago Humanities Tapes is produced and hosted by me, Alisa Rosenthal, with help from the awesome staff over at Chicago Humanities. Shout out to the wonderful staff who are programming these live events and making them sound super crisp. For more than 30 years, Chicago Humanities has created experiences through culture, creativity, and connection. Check out chicagohumanities.org for more information on becoming a member so you’ll be the first to know about upcoming events and other insider perks. You can also check out our backlog of episodes from season one of Chicago Humanities Tapes, available wherever you stream your podcasts. We’ll be back in two weeks with a brand new episode for you. But in the meantime, stay human.

[Theme music plays]

[Cassette player clicks shut]

SHOW NOTES

CW: Language, LANGUAGE

Watch Harold Ramis’ full program here

Harold Ramis at the Chicago Humanities “Laughter” Festival in 2009

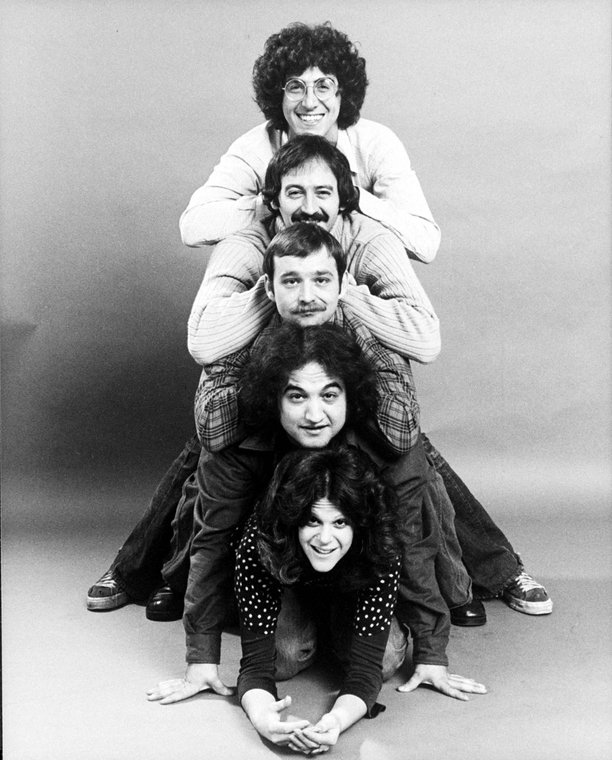

Harold Ramis, Joe Flaherty, Brian Doyle Murray, John Belushi and Gilda Radner in 1974, NYPL Digital Collections

Watch John Waters' full program here.

John Waters, Liarmouth: A Feelbad Romance

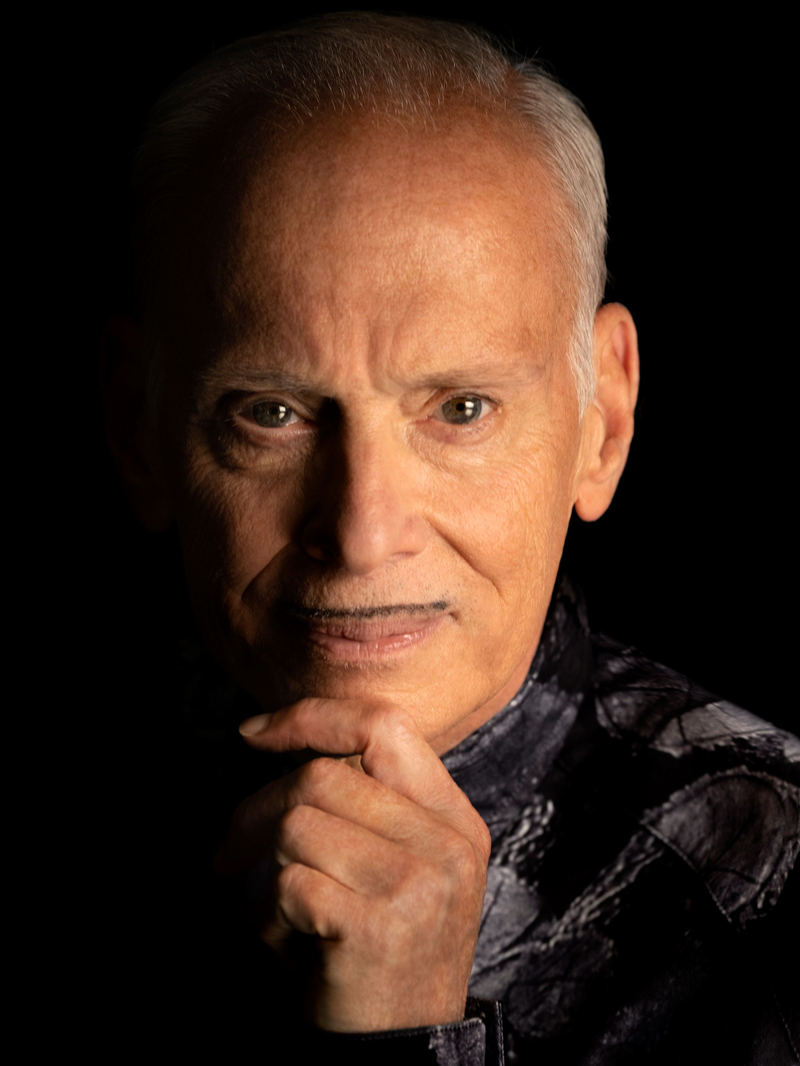

John Waters portrait by Greg Gorman

Divine and John Waters in 1981, Roxanne Lowit

Recommended Listening

- Podcast

- April 4, 2023

Bob Odenkirk with Tim Meadows on Finding Your Comedy Voice

- Podcast

- February 6, 2024

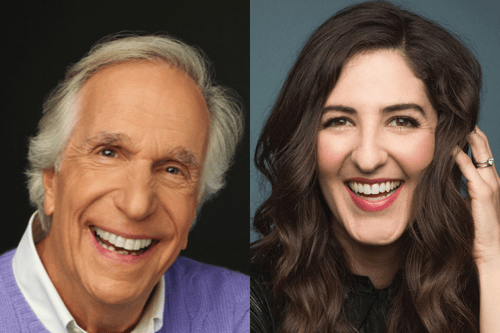

Henry Winkler: Lessons from a Real Sweetheart

- Podcast

- June 13, 2023

Selma Blair: MS, Writing, and Parmesan Cheese

Become a Member

Being a member of the Chicago Humanities Festival is especially meaningful during this unprecedented and challenging time. Your support keeps CHF alive as we adapt to our new digital format, and ensures our programming is free, accessible, and open to anyone online.

Make a Donation

Member and donor support drives 100% of our free digital programming. These inspiring and vital conversations are possible because of people like you. Thank you!