Mini Tapes: Guidance from the Afterlife

S3E7: Tracy K. Smith

Apple Podcasts • Spotify • Pandora • Overcast • Pocket Casts

Today’s bonus episode brings us Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Tracy K. Smith in conversation with Parneshia Jones, the Director of Northwestern University Press. Smith, the 22nd Poet Laureate of the United States, shares of the times she looked to her ancestors for guidance - or rather, how they found her.

Read the Transcript

[Theme music plays]

[Cassette player clicks open]

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Hey everybody, thanks for tuning into Chicago Humanities Tapes - the audio extension of the live Chicago Humanities Spring and Fall Festivals. I’m Alisa Rosenthal, and this is Mini Tapes, a special episode where we bring you one great selection from one great program. Today: Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and 22nd Poet Laureate of the United States Tracy K. Smith with Director of Northwestern University Press Parneshia Jones, in conversation about the meditative quality Smith’s life took on after the racial reckonings of 2020, and how she looked to her ancestors for guidance - or more accurately, perhaps, how they found her.

This conversation was recorded live at the Chicago Humanities Fall Festival at the University of Chicago in 2023.

[Theme music plays]

PARNESHIA JONES: Hello. Nice to see you all. How are we doing? Oh, good, good. It's Sunday, so we get to bless and restart our lives in so many ways. When I was reading this book, I was thinking about Alex Haley. I was thinking about Zora Neale Hurston. And this idea of history. But the anthropology of history, if that makes sense to you all. Like the last bones of our people. And it's not just claiming a history, it's not just discovering people discover things all the time. They don't always know what to do with it, and they don't always do the right thing by it. And so can you talk about the claiming of the histories that you found, which is your own history. The claiming of the histories that you found, and how it's led back to you and how you move forward in the world now.

TRACY K. SMITH: Yeah. Well, it takes me a little bit back to the meditation because I was really asking for guidance and help. How do I, how do I even think about what what I ought to be doing and how I ought to do that. And I really do believe that ancestral voices and guides interceded. Even my you know, both of my parents passed away, my father more recently in 2008. And I am the child in my family who inherited all of the papers and military records and photographs and all of these things. And I felt like my father said, I'll help you, in fact, open this box that you've never opened before. Open this envelope, read this letter, and now look over here. And I feel like he showed me the real story of his life, things that had to do with living in the 20th century as the head of a large household serviceman in the Air Force and dealing with an extremely heavy responsibility and doing it silently and with such grace that his children had no idea the difficulty, and then meandering through archival records, looking for just evidence of his family. Our people. I found more. I found a letter that a neighbor of my grandparents had written to the governor of Alabama during the Great Depression. And it's a really courageous letter. And it's a letter where you can hear this man's voice. I describe almost being able to see his hand gestures because it's so full of the desire to be understood and heard. And he's basically saying all the colored people have been laid off from work. I just arrived today to learn that I, too, have been laid off, but I don't think we're being treated fairly. Many of us have large families to take care of. And he talks about the price of food and he doesn't know where help is coming, but he asks that some be sent. And then he gets a letter back from the governor's representative that is maybe like the prototype for AI, just so bloodless, a sentence that leads almost through a labyrinth that arrives nowhere, basically. And so I can just feel the limitations of care and also the wonderful resilience and inventiveness and improvisation by which communities of people made do made a future possible for their their, you know, children and grandchildren and so forth. I feel like I hold that in me now. I feel like those voices and those versions of truth helped me make better sense of my own life, be it, you know, albeit different. And I just want to invite all of us to kind of like sit at the feet of these voices, which are often tucked away in corners of the archive if they even make it there. But they're full of what's missing from our view of who and what we are as a nation. I, I want to make a big case in this book that these are quiet lives that are essential to this massive enterprise of of liberation.

PARNESHIA JONES: It's perfect. Thank you.

TRACY K. SMITH: There's an anecdote at the very end of this book about a poetry reading that I gave in Kentucky during the Laureateship, and I read from a number of Civil War poems, and they were really found poems, verbatim letters by black soldiers in the Civil War and their family members, verbatim lines from deposition statements given after the war and an attempt to claim the pensions that they were entitled to, but that many blacks were denied at that time because they didn't have the paper documents that emancipated or people who were, you know, whose freedom was considered inalienable from their very persons would have had. And so this woman came up after after that reading, and she said all those voices, they were so powerful. And they reminded me of my beloved grandmother. Would you please wait for me? I just want to go get something and I want to give you something. She took a long time to get home in what was a pretty small town, but she eventually came back and she looked really worried. It was like, What happened? And she said. My siblings and I love our grandmother so much that when she died or before she died and she lived to be in her nineties, we recorded her and we asked her to tell us stories and sing a lot of the songs that she knew and that she had sung to us when we were growing up. And I guess she had gone back home and listened to this recording that she wanted to gift to me. And she said. My grandmother would never have wanted to hurt you. And I said, Oh, of course. These old Kentucky songs. What do they have to say about me and my people? And I also thought, I have to give this woman credit. She could have stayed home. She came back and she kind of announced that this artifact exists and she now sees it and understands it differently. And in my mind, what I like to imagine is that her grandmother, just like my dad was like, go in that box, get that. Her grandmother said, Go get that. And now think about it. I think it's time for us to tell different stories. And so I really believe that there is a dimension of the afterlife or whatever we want to construe it as that even is willing to change their value system because they now see the bigger picture. And so I want to summon that as an ally for us in doing what we have to do.

PARNESHIA JONES: That's so leading into my next question - it’s not only the Black experience, it's the absolute Black experience. And. Wait for it. You choosing not to blame anybody? I think that's an extraordinary thing to do. As a writer. Now we can blame people. We can spend all day bank blaming people. But you actually don't put blame. You just lay out the facts. You record your ancestors and you respond in the ways you feel is a human response. But you don't blame anybody. And so you're choosing not to blame. Any one race or history. And this speaks to what you just said here. But you show up with receipts. Receipts and our collective. No matter how divided we are. Collective and brought sold oppressed histories. They're all collective. We own it. We've all been bought and paid for. To some extent. And so some people can't answer for ancestral pain or oppression or the monstrous. And. What do you expect? Expect for the black experience? If. And only if. It is fully. Accepted as the absolute American experience.

TRACY K. SMITH: Hmm. I believe that's what it is. I know that's what it is. And I know that Black life. Is full of love. When you belong. I'll use that word in many ways to a country that does not. Love you. You create more love. To share and sustain the people in your your kin, your kith. I feel like the archive, all the silence that we discern and now that we know how to name, is as violence, as erasure. I think it's filled with love. I think endurance is love. I think discipline, even the silence by which my father kept some of those things from me, I know that was about wanting me to feel large. And I think a big part of love is also forgiveness, grace. And that, you know, there are a lot of lessons America doesn't want to learn from us. But I wonder if that could be one. In order to I mean, a lot of things have to happen in order to change, you have to realize that you, no matter how powerful you believe yourself to be, no matter how free you imagine you have always been. There comes a moment when maybe you're you might be willing to realize you are captive in a system. You are captive in a system that demands that you wield your power and wield your freedom against others who you have been convinced are trying to take it from you. So that's that's a lot of labor. But what might it mean if you were willing to say, I forgive myself? I forgive myself for what I've done and what I've benefited from simply by my birth. And now I want to free myself to do some building or rebuilding. That's kind of what I'm hoping we might broach because we're so good at blaming each other. We're so good at building up a sense of righteousness and leveling judgment and doing it in pithy ways, doing it in, you know, like little images on Instagram. But that doesn't really get us where we need to go. It just rigidifies the division and the fury that's keeping us, you know, stuck. So I have this wish that we could exercise a different kind of care toward ourselves if we haven't been taught to do that and then understand how how much our care and contribution is needed elsewhere.

PARNESHIA JONES: It's so perfect. Thank you. Thank you for that.

[Theme music plays]

ALISA ROSENTHAL: That was Tracy K. Smith and Parneshia Jones at the Chicago Humanities Fall Festival in 2023. For the full story, head to the show notes for the link to the video of this event as well as more information on Tracy K. Smith’s book To Free the Captives: A Plea for the American Soul.

This mini episode of Chicago Humanities Tapes was produced and hosted by me, Alisa Rosenthal. New episodes drop every other Tuesday, available on all streaming platforms. Head to chicagohumanities.org to learn more and check out all our episodes featuring your favorite speakers with some of the most interesting ideas, and you can also find our live event calendar for tickets if you’re in the Chicagoland area. Thanks for listening, and as always, stay human.

[Theme music plays]

SHOW NOTES

Watch the full conversation here.

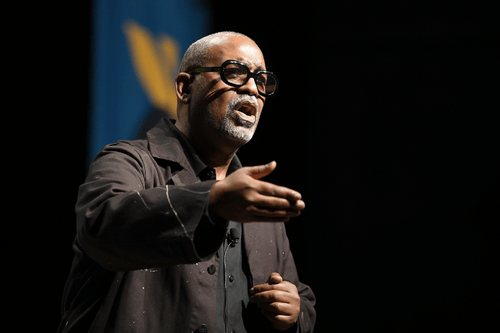

Tracy K. Smith ( L ) and Parneshia Jones ( R ) on stage at the University of Chicago at the Chicago Humanities Fall Festival in 2023.

Tracy K. Smith, To Free the Captives: A Plea for the American Soul

Recommended Listening

- Podcast

- February 20, 2024

Throwing Poems into Lake Michigan with Sandra Cisneros

- Podcast

- April 3, 2024

Getting Schooled in Hip Hop with the Notorious Ph.D.

- Podcast

- April 16, 2024

Mini Tapes: What We Can Learn About Social Media From Foxes

Become a Member

Being a member of the Chicago Humanities Festival is especially meaningful during this unprecedented and challenging time. Your support keeps CHF alive as we adapt to our new digital format, and ensures our programming is free, accessible, and open to anyone online.

Make a Donation

Member and donor support drives 100% of our free digital programming. These inspiring and vital conversations are possible because of people like you. Thank you!