Mini Tapes: What We Can Learn About Social Media From Foxes

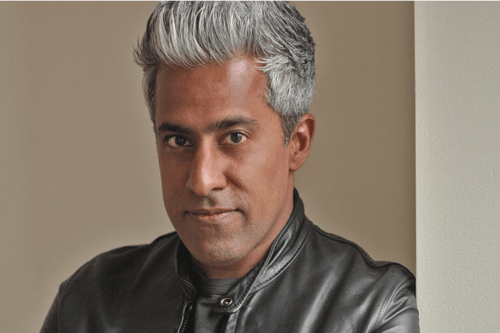

S3E6: Max Fisher

Apple Podcasts • Spotify • Pandora • Overcast • Pocket Casts

New York Times investigative reporter and author Max Fisher chats with The Verge editor at large David Pierce about a ‘50s era female Soviet scientist, her study of foxes, and what they have to do with social media today in our first ever mini episode: one great story from one great program.

Read the Transcript

[Theme music plays]

[Cassette player clicks open]

ALISA ROSENTHAL: You’re listening to Chicago Humanities Tapes - the audio extension of the live Chicago Humanities Spring and Fall Festivals. I’m Alisa Rosenthal, and this is Mini Tapes: one great story from one great program. Today: New York Times investigative reporter Max Fisher is joined by David Pierce, editor at large for tech website The Verge. You’ll hear Max Fisher spin a fascinating tale about a ‘50s era female Soviet scientist, her study of foxes, and what they have to do with social media today. This conversation was recorded live at Chicago Humanities as part of our “Social Mind” Verge series at Steppenwolf Theater in fall 2022.

[Theme music plays]

DAVID PIERCE: The first thing I want to do is I want you to tell us the story about foxes. This is a strange place to start, but go with us. It all comes back around, I promise. But that was one of the things that jumped out to me the most in reading your book that felt like sort of a perfect microcosm of social media, the whole thing. So can you just tell all of us the story of the foxes?

MAX FISHER: Yes. I'm so glad that we are starting with this. So just to warn everyone, like you said, this is not something that is initially going to sound like it's a story about social media. I promise it becomes a story about social media and how it affects us, how it changes. It's going to sound at first like it's a story about an old Soviet lady in Siberia hanging out with a bunch of foxes. Because it is so.

DAVID PIERCE: It is exactly that story.

MAX FISHER: Yeah, that's right. So in the 1950s, there was this Soviet geneticist named Lyudmila Trut who wanted to discover this mystery that had been the heart of genetics going back to Darwin, which is what, if anything, is the genetic basis for the domestication of animals. What's what is there a genetic reason that domesticated dogs are different from wolves, horses, cows? Is there a reason that they all have common physical traits, like they have floppier ears, they have flatter faces, they have smaller heads. What's going on here? And trying to understand what are the origins of that? So in the 1950s, it was actually illegal to study genetics in the Soviet Union for weird political reasons. So Lyudmila Trut to study this, to try to understand what are the origins of domestication. She took over part of a, uh, a fur farm, in way in the middle of nowhere in Siberia that bred foxes for fur coats. And what she did when she said she was going to do this experiment that she knew at the outset was going to take 50 years, and it did take 50 years to breed one generation of foxes after another by taking the 10% friendliest foxes out of any generation and just breeding those. And she what she hoped was that over many generations of this, eventually they would domesticate and that would allow her to identify what caused this. And sure enough, after many, many years of doing this, what a great job, by the way, just to hang out with foxes all the time. I think it sounds awesome.

DAVID PIERCE: But only the nice ones only.

MAX FISHER: That's right. Only the only the friendly ones. Yeah. What she did in fact find was that there was a moment when suddenly they domesticated and she was able to isolate down a specific biological, chemical, physical change that happened in the foxes, which there's this specific kind of cell that develops in utero that was being suppressed. There's a specific set of hormones that were being suppressed, and that led to the foxes being much friendlier, much more cooperative, much more social, much more able to be around each other, less aggressive, and then also having these physical changes. And what was interesting about this and what made this discovery like one of the biggest discoveries like in all of science, I think, in the last 50, 60 years, was that the physical markers that she found happened to line up perfectly, just identical match to a set of changes in us, in humanity that happened just as we became Homo sapiens 250,000 years ago, where at that moment we transitioned from living in very small groups to living in suddenly much larger groups of like 100, 150, suddenly dominating our environment, being much smarter that we had the same change that happened in domesticated animals. So that opened up this mystery: how did we domesticate? Because with the foxes, with every other animal, there is a person there to intervene to artificially promote these friendlier animals that were not going to reproduce so successfully anyway. But as best we know, 250,000 years ago there was not a Soviet geneticist running around selecting for the nicer people on the step and putting down the less nice ones. So that opened up this whole second journey, and I will spare you the details of how they finally got to the answer to this. But working with this English anthropologist named Richard Wrangham, she finally figured out that what had happened 250,000 years ago was that we developed language and what developing language allowed us to do was to overturn the social order that had dominated in our species and in predecessor species for like 10 million years, which is alpha males dominate the group, which is a small number of males who are the most aggressive, the most violent, the most domineering, that they control the group. They are the ones that reproduce. No one else does. And what had happened with the development of language was that all of the other males, the beta males, were able to get together, were able to say, this sucks, we don't care for this. And what we're going to do is because we have strength in numbers and we have the ability to coordinate now with language, we're going to overturn the alpha males and we're going to impose this new order where we rule collectively through consensus. And this was turned out to be an identical process to what Lyudmila Trut was doing with the foxes, which it was selecting at a genetic level for friendliness, for cooperation, was also selecting, for conformity, for a willingness to go along with the group. And crucially, and this is where I promise we're getting closer to social media, selecting for a propensity and a willingness and even a drive to commit basically violence on behalf of a group against someone who is a moral or social transgressor, someone who is a bully, who is an alpha male, who is pushing around the rest of the group with a group didn't like, because what had to happen? You overturn the alpha male, now you have to enforce this new order. Now you have to enforce what Richard Wrangham, the anthropologist who worked on this, he called it proactive coalitional aggression. It's a fancy way of saying a lot of people coming together as a group and deciding to commit some sort of violence on behalf of the group. As philosopher named Ernest Gellner had a more fun name for it. He called it the tyranny of cousins. This is something you still see in hunter gatherer societies today where the basically the the beta males or all of the males in the group get together and they decide what the norms of the group are and they enforce it collectively through consensus. And we have another name for it, which is a mob mentality. And this this instinct, this behavior that turned us into Homo sapiens, and it was selected into us over 250,000 years. This is the foundation of who we are as a species. Literally, the thing that turned us into the human animal and what is important to understanding about this is the set of behaviors, instincts that this ingrained into us and made us many of our deepest instincts. One of them is moral outrage. Moral outrage is the trigger for this aggression. It's how all of the beta males come together. It's how you enforce the tyranny of cousins, it's how you enforce these social norms. As you say, there's someone who's transgressing the group and we're going to go out and we're going to get them. It creates these conformity impulses, this idea that if your community believes something, you start to believe it too, because that has been bred into over 250,000 years. The way that your brain works is to reproduce this thing that was happening, you know, on the East African steppe that turned us into the species that we are. And how this brings us now finally to social media is that what happens? After 25,000 generations of this is a bunch of companies come along and they develop technology that does a lot of things. But one of the most important things that it does is that it uses I mean, first of all, it severely heightens our sense of being in a social group, in a social dynamic. I sense that we are experiencing things socially through that kind of group behavior it is is just supercharging everything on it. But the more important thing that it does is that it conducts billions of experiments a day on all of us and anyone who is on the platform to determine what is the precise combination and sequence of emotions of language. Because remember, language was the thing that triggered this in the first place of a social stimulus that is going to be most engaging to us. And we know and we know from also lots of social science research that's happened over the last 20 or 30 years, that the thing that is most engaging to us is anything that hits on this impulse that we have for this tyranny of the cousins, for this mob mentality, because that is so deep in us. And I know you have a lot of questions about what that actually means about social media, but I think the thing that is really important to understand is the moral outrage that you encounter so much online and the sense that we are outraged as a group. There's someone who's a transgressor. There's someone who is doing something that we don't like and we're all going to yell at them. We're going to punish them. We're going to get upset about it. When you see that happening on social media, it's not just that outrage happens to be a particularly stimulating emotion. It is the most stimulating emotion. And that is because it is something that goes to the core of who we are as a species and we see people acting on that. You are seeing that instinct that is so deeply ingrained within us that has been brought out by these social platforms and amplified on a scale that is entirely new in the human experience.

DAVID PIERCE: Well, I think there's something crucial there that I want to press on a little further, which is the difference between regular outrage and moral outrage, because it's like it is a truism of the Internet that everybody's mad all the time. Right?

MAX FISHER: Right.

DAVID PIERCE: And everybody's mad that, like they got bad service at Starbucks and they're mad that, like, their shoes were smaller than advertised on Amazon. But this this thing you're describing, this like more more sort of effective thing is moral outrage. They just sort of paint the difference between outrage and moral outrage. [18.7s]

MAX FISHER: So moral outrage is anger that you feel on behalf of your community against a social transgression, against someone who is doing something to transgress against the group. The most basic way is you see someone cutting online and you get upset and you want to say, Hey, don't cut online, don't be a jerk. That's moral outrage. And when you see someone else expressing moral outrage, that is something that taps into this instinct that makes you, first of all, pay a lot more attention, because it is it is these social impulse that allowed us to survive as a species. So it's something that is just hardwired into our brain that actually this is fascinating experiment where these researchers to try to test like, okay, is moral outrage actually the most engaging form sentiment? Because there's a lot of reason to think it is. But how can we know that for sure? Is they would run these screens in front of people or they would flash all of these different words at them. And they found that no matter what kind of emotional valence was in those words, if it was a sad word, a happy word, an exciting word, that it was the moral outrage words that if it appeared anywhere on the screen, people's eyes were just dart to it before their brain could even process it, even compared to exciting words like explosion or car wreck. If it was something that, you know, liar, cheater, anything that tapped into this sense of someone who is transgressing against the moral norms of the group, that it just grabs your attention more than anything else. And sure enough, on social media, that is what the systems learn to promote above all else, not just because it captures our attention, but because it spurs us to action more, literally more than any other emotion. It makes us want to go along and to get outraged, too. And the platforms love that because it means now you're not just spending more time browsing, you're posting content yourself that spreads that moral outrage that will get other people to post back.

DAVID PIERCE: So I told you it came back around, by the way, it's, good work. It came around. We got there.

[Theme music plays]

ALISA ROSENTHAL: That was Max Fisher and David Pierce at the Chicago Humanities Fall Festival in 2022. For the full story, head to the show notes for a link to their hour long video as well as more info on Max Fisher’s book The Chaos Machine. This mini episode of Chicago Humanities Tapes was produced and hosted by me, Alisa Rosenthal. New episodes drop every other Tuesday, available on all streaming platforms. Head to chicagohumanities.org to learn more and check out all our episodes featuring your favorite speakers, as well as our live event calendar for tickets if you’re in the Chicagoland area. Thanks for listening, and as always, stay human.

[Theme music plays]

DAVID PIERCE: If you're about to tell me a story about how good MySpace was, first of all, I'm very here for it. Second of all, that is dangerous territory.

[Cassette player clicks closed]

SHOW NOTES

Watch the full conversation here.

Max Fisher ( L ) and David Piece ( R ) on stage at Steppenwolf Theatre at the Chicago Humanities Fall Festival in 2022.

Max Fisher, The Chaos Machine

Recommended Listening

- Podcast

- April 18, 2023

Is the Public Still Persuadable? with Anand Giridharadas

- Podcast

- March 5, 2024

Rachel Maddow on History, Now, and What’s Next

- Podcast

- April 30, 2024

Mini Tapes: Guidance from the Afterlife

Become a Member

Being a member of the Chicago Humanities Festival is especially meaningful during this unprecedented and challenging time. Your support keeps CHF alive as we adapt to our new digital format, and ensures our programming is free, accessible, and open to anyone online.

Make a Donation

Member and donor support drives 100% of our free digital programming. These inspiring and vital conversations are possible because of people like you. Thank you!