Throwing Poems into Lake Michigan with Sandra Cisneros

S3E2: Throwing Poems into Lake Michigan with Sandra Cisneros

Apple Podcasts • Spotify • Pandora • Overcast • Pocket Casts

Acclaimed poet and author Sandra Cisneros graces our ears with a cacophony of creative inspiration, images of Mexico, and poems that glide in and out of Spanish. She chats with author and professor Daisy Hernández live at Northwestern University, in a conversation that will leave you running for your pen.

Read the Transcript

[Theme music starts]

[Cassette player clicks open]

SANDRA CISNEROS: The writing is the thing that has saved me. And it's cheap, you know, you don't need to get paints, you don't have to get funding for a film. Very inexpensive hobby, but keep your day job.

[Audience laughter]

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Hellooo and thanks for joining us back at Chicago Humanities Tapes. We are the audio arm of the live Chicago Humanities spring and fall festivals. I’m Alisa Rosenthal, and I’m here to bring you the best bits of the best chats from our oeuvre. We’ve got some very cool live events coming up - including ABC News Chief Anchor and former White House communications director George Stephanopoulos - he’ll join us at IIT on May 18th with David Axelrod. Head to chicagohumanities.org to learn more and snag tickets.

Let’s get into it! As you could tell from the cold open, this program is such a gem. Poet, author, and Chicago-native Sandra Cisneros penned the bestselling novel “The House on Mango Street” - which won the American Book Award, and which I read and loved in high school, shout out to Evanston Township High School for that reading!

Her other honors include fellowships from the National Endowment of the Arts and the MacArthur Foundation, and in 2016 she received the National Medal of Arts awarded by President Obama. Her most recent book of poetry Woman Without Shame celebrates and explores her experiences of being Mexican, being a woman, and a poem called “My Mother and Sex.” It’s great.

She chats with Professor Daisy Hernández, an essayist, journalist and an associate professor in the English Department at Northwestern University, where this conversation also took place. She's an award winning author and reporter for The New York Times, The National Geographic, The Atlantic and Slate. Check the show notes after you finish listening to the program for links to all the works they mention in their chat; you won’t be disappointed.

This is Sandra Cisneros with Daisy Hernández, live at Northwestern University’s Pick-Staiger Concert Hall in Fall 2023.

[Theme music underscores]

[Audience applause]

SANDRA CISNEROS: Thank you for coming out in the rain and wind. These are diehard fans.

DAISY HERNÁNDEZ: Muchas gracias, yes. Hello, everyone. So wonderful to be with you and Sandra, bienvenida a Northwestern.

SANDRA CISNEROS: The first time I've ever been here, I think. No, that's not true. I came to hear a concert by Leo Brouwer, the Cuban composer, when I was very young. Yeah, because he asked me out afterwards.

DAISY HERNÁNDEZ: Now, we might get to hear some secrets today.

SANDRA CISNEROS: I was so shocked. And if I didn't have my brother Carlos with me, I would have gone.

DAISY HERNÁNDEZ: Los hermanos, they often get in the way of the fun stuff happening in our lives. You know, I want to start by actually thanking you, Sandra. I was reading Sandra's books when I was a teenager on a public bus in New Jersey many, many years ago. And it was the first time that I saw myself and my family in a book. And I haven't had a chance to publicly say this before. So thank you, because it made me a writer and I would not be here today as a writer and at Northwestern if it had not been for you and your book. So thank you so much. I really.

SANDRA CISNEROS: Wow.DAISY HERNÁNDEZ: I really appreciate it. Let's start by talking about poetry. So I was thinking about who I was when I was 18 and that age. And I remember that the question that I had back then is a question that I often get when I teach Introduction to Creative Writing, which is, what is a poem? What makes a text a poem? And has that definition changed for you over time?

SANDRA CISNEROS: Before I answer that, I need to ask how many people here are teachers? Oooh. All right. Wonderful. Bravo. You are courageous and you are my heroes. And how many people here are librarians? Ooh hoo! You know, the teachers and the librarians are doing the bravest work I know in these times. So I applaud you for, thanks to the teachers and librarians who made me a writer, I thank the Chicago Public Library that my mom took us to the library and, you know, it was a teacher in the sixth grade that changed my life. I went from a school where there were very unhappy teachers there, and we moved to the north side, and I went to school at Sisters of Christian Charity, and there was a teacher in the sixth grade that changed my life. And she did something that I had never had done before, and that is she saw me with ojos de amor. She saw me with eyes of love and she singled out something I could do that was positive instead of being singled out for negative. And she picked up a piece of artwork and put it up on the the front of the room and said, This is what our new student has done. Isn't this beautiful? And at first, when she picked up my paper, my my heart just leapt. I thought, what did I do wrong? That was the old school. And I was sure that she was confused and had mistaken me for someone intelligent because I had just gotten some new little blue glasses with pointy from the Sears. I had just gotten them and I thought, She thinks I'm smart. Oh. And I felt sorry for her. It is a grave mistake to think I was smart. I had C's and D's and this is not a lie. You can look at My House of My Own: Stories From my Life essays. There's an essay called A Girl Called Dreamer. And my report card is there to prove to you I'm telling the truth. I had C's and D's, and this teacher saw me con ojos de amor and singled out what I could do. And because she had faith in me, I did something I'd never done at the other school. And she asked a question. I raised my hand even though I knew the answer in the other school I didn't dare. But in this school, this teacher was the first one that had faith and and showered me with love and attention. And I tried and I moved up from C's and D's to B's and C's and eventually when I graduated to A's and B's. So it makes all the difference. A teacher and or an individual or a parent that gives you just pur amor. Yeah, amor puro. And that's the secret, no? That's the secret.

DAISY HERNÁNDEZ: Absolutely.

SANDRA CISNEROS: But I was I was getting a roundabout way to what is a poem which many people ask, even in my own family. So I want you to explain to all of you what is a poem? Every poet will have a different answer. But for me, it's very clear that a poem is music with words. And it's like jazz. You know how like, you know your drummer, you take sticks and you're always hitting them against metal or you're hitting them against your cup or against the floor or whatever you find it get a different sound. You're doing that with words. As a poet, you're moving them around and you're playing with them and you're finding delicious words. You're finding words in other languages and you're moving them around and you're just you're just improvving and you're making music with words. And that to me, is one of the things that poetry is. And the other thing is poetry is an emotion that comes in your heart that doesn't have any words. You can't speak about what it is. It's just this blurry thing in your heart. And when people say, Well, how are you, usually tell them, Fine, but that's not true. If you spend some time by yourself quietly and you wrote down, Well, I think I'm and then just keep writing and writing something would blossom out of that compost. First you start with junk and you just say, I think I'm fine. Well, not exactly. And you keep following it and following it and following it till some little flower blooms from that compost. That's a poem. And you don't know what it is when you begin. If you know what it is, you should write an essay or a story. But a poem is something that's a that's a motion that is lodged in your heart. It's like finding a pebble in your shoe or a thorn in your thumb. And when you pull it out, you say, Oh. That's what it is. So you have to stalk and follow a poem, and that means time. And sometimes it takes several hours or several months or several years before you can pluck that thorn from your heart and say, Oh. This is what I was feeling and I didn't know it. And that's the beautiful thing about poetry, because it keeps us healthy so that we're not angry at other people. It keeps us healthy when we're sad and transforms our pain to light. It makes us better human beings to be around others. It celebrates joys. Whatever you're feeling it, it's therapy for your heart. And who doesn't want that right? It's like you're doing self therapy, self love, self care. That's poetry.

DAISY HERNÁNDEZ: Beautiful. Thank you. You're reminding me that there were so many times when I was reading this new book, A Woman Without Shame, where I had those moments of like, you know, no words, but just oh, I had like such an emotional and visceral response to a line that you had. So this is a book that celebrates being a woman, a mujer, a Latina, and you wrote early in the book, "I was in training to be a woman without shame." And you pointed out that that's different from shameless. So sinvergüenza not compared to sin vergüenza. So can you talk with us about what that difference is that's so powerful and maybe you'll read from that poem too?

SANDRA CISNEROS: I have to say that everything in my life, all the writing has started from a place of shame. I was shame of being not the smart one in the classroom. And I was a shame of not having the right shoes and not at being pretty and not feeling loved in public. I was loved at home, but like when I went out to the schools, I felt less than. So there was a lot of shame, and writing has helped me to survive that. And as soon as you conquer one shame, another shame pops up in your life. How do you like that? So now I'm 68 and I have different shame than I did when I was a child. But the writing is the thing that has saved me and transformed me. And. And it can transform you. And it's cheap, you know, you don't need to get paints. You don't have to go to the paint store. You don't have to get funding for a film. You know. You know, you can use a pencil or any pen and a piece of paper. You don't have to have a laptop. You know, it's very inexpensive hobby, but keep your day job. All right. This is an answer to the question. A woman without shame. And, you know, a lot of times we have memories of things that have happened to us and we don't know what they mean. So this poem came up very easily because I was thinking about a time in my life when I wanted to get over a shame of my body. And, you know, so I'm just going to read the poem and the poem explains it. "Tea Dance, Provincetown, 1982. At the boy bar. No one danced with me. I danced with every one. The entire room. Every song. That's what was so great about the boy bars then. The room vibrated, shook, convulsed in one collective zoological frenzy. Truthfully, I was the only woman there. Who cared? At The Boat Slip I was welcomed. The girl bar down the street, dull as Brillo. But the tea dances shimmied, miraculous as mercury, acrid stink of sweat, chlorine, tang of semen, slippery male energy, something akin to watching horses fighting. Something exciting. My lover. The final summer he was by introduced me to the teas, often hovered out of sight, distracted by poolside beauties while I danced a innocent content with the room of men. He was a skittish kite that one. Kites swerve and swoop and whoop. Only a matter of time I knew. Apropos I called him, my little piece of string. And that's what kites leave you with in the end. There was an expiration date to summer. Understood. That season I was experimenting to be the woman I wanted to be. Taught myself to sun topless at the gay beach where sunbathers shouted "Ranger!" A relaid warning, announcing authority in route on horseback coming to inspect if we were clothed. Else? Fined $50 sans bottom, 100 topless - 50 a tit I joked. It was easy to be half naked at a gay beach. Men didn't bother to look. I was in training to be a woman without shame. Not a shameless woman. Una sinvergüenza, but una sin vergüenza. Glorious in her skin flesh akin to pride. I shared that summer not only bikini top but guilt driven Eve and self immolating Fatima. Was practicing for my Minoan days ahead Medusa hair and dress spectacular as Nike of Samothrace welcoming the salty wind. Yes, I was a lovely thing then. I can say this with impunity. At 28, she was woman unrelated to me. I could tell stories. I have so many to tell and none to tell them to except the page. My faithful confessor. Lover and I feuded one night when he wouldn't come home with me. His secret? Herpes. Laughable in retrospect, considering the plague was already decimating dances across the globe. But that was before we knew it as the plague. We were all on the run in '82. Jumping to Laura Branigan's "Gloria!" The summer's theme song, beat thumping in our blood, drinks sweeter than bodies convulsing on the floor." So when you begin a poem. You don't know where it's going. If you like I said, if you know where it's going, then you shouldn't write a poem. You know write an essay or story. So I had no idea where that was going. It just was a memory and it took me to places I didn't expect. And if you're ashamed of where it's taking you, you're on the right track. So you should always make a list of the things you wish you could forget or the things you're ashamed of, and write about that. And then guess what? You're not ashamed anymore. That's the wonderful thing. Or if you're still ashamed, you learn how to live with it. And so a lot of poetry that we write, we don't write it to hold it up or publish it. The real reason we need art is to make peace with ourselves, to feel better, to go on with life, to celebrate our day, to forgive ourselves, maybe forgive others. It's very therapeutic. And that's the real reason. The best writing you'll do will be the one you can't show anyone. If you feel like, Oh, no, I can't show this to anyone, you're on the right track. That's why it took 28 years, because many of these I, I write them and like Emily Dickinson, I throw them under the bed and then it takes several years before I take them out again and say, I think this might help somebody. And I'm not ashamed anymore. And I send it out like that.

DAISY HERNÁNDEZ: Beautiful. You're reminding me that many years ago, you gave me a wonderful writing exercise. I asked you, this was at a National Women's Studies conference a long time ago, maybe 2007. And I went up to the microphone. I was so nervous. There were like, I don't know, 500 people in the audience. And I was like, So I'm having writer's block. And what's your advice? You're like, There is no such thing as writer's block. I was like, Are you sure? Because I'm having it right now. And you said, You're just afraid. You're afraid. So what you do is you go home and you write, This is what I am afraid to say. I am afraid to say that... And oh, my goodness, I actually went back to my room that night and I started writing and it completely freed me up with the piece that I was working on.

SANDRA CISNEROS: Because a lot of times when you have writer's block, it's because you're thinking about the reader or the listener. It's the same thing like when you speak and you stammer, you stammer because you're concerned about the listener who's listening to you. The same thing with when you write. You can't think about the reader, otherwise you can't write anything good. You have to imagine that what you have to say is too dangerous to get published in your lifetime. And sometimes it is. And sometimes you have no privacy. If you grew up like me in a house with no doors, there's no privacy. I tell young people, make sure you have privacy. And if you don't, you can write it and then you can eat it. You can tear it up and throw it in Lake Michigan. You can burn it in an ashtray, you know, whatever you have to do, but you have to be able to express these emotions. We can't hold all the emotions that we feel every day. So many things happen to us and some are painful. For me the stories I write about that are my hits are things that I held for years. My story 11 is something that happened to me at nine that I held on and couldn't speak about till I was 30. And imagine, you know, holding the things we've seen or heard or things people said to us, it's very painful. We have to let them go. And even if you don't publish them, you know, put them on the page. You can make a ritual and you can you don't have to keep it. You don't have to show it to anyone, but you do have to process. It's a composting. No?

DAISY HERNÁNDEZ: Beautiful. Yes. So I'm going to confess that when I opened up the book, you know, I always like to look at the table of contents to see how the poet organized the poems. And I like to see the titles. And there was one titled My Mother and Sex. And so I immediately went to that poem and skipped ahead.

SANDRA CISNEROS: I do not worry. This is the G rating reading, ok? If you want the adult reading, you can go to the last section, Cisneros Sin Censura. And you young people do not read this book. Do not.

DAISY HERNÁNDEZ: I. So I'm hoping you will read that poem. And but.

SANDRA CISNEROS: This is a G rating poem. Yeah.

DAISY HERNÁNDEZ: Yeah. No, it's it's a beautiful poem. And what I wanted to ask was that, you know, I don't know if my that reaction of mine was like being Latina, being a woman, you know, I just that is still so taboo to talk about this subject and our mothers, but also this book is so much about pleasure and all its ways, you know, and and so much also about aging as well as a woman. And I and I feel like you are trailblazing yet again because I realized I don't feel like I have a blueprint necessarily.

SANDRA CISNEROS: Well, you know, you know, when I started getting older, I knew that I was didn't think like others. When you go to the lingerie department and things that are size large or extra large or XXL all come in beige, white and black, you know, very boring. And I said, What's the matter with our society? Right? So I wrote a poem about that, but I'm not going to read that. I read the one, My Mother and Sex. You know, my mother was an incredible person and very self-educated. She met incredible people and took us to the library. But she could talk about politics, anything that's going on in the world. But you could not talk about her private life. So this is a poem about that. My Mother and Sex. "Eight live births. How many dead? Who knew? Not us. Her seven survivors. When a bedroom scene flashed on TV, she'd shriek and scamper to her room as if she'd seen a rat. It made us laugh. What were we? Immaculate conceptions? Could be, sex for her was dead a duty dreadful as cooking for her famished army. Sad to think this, pure postulation from lack of conclusive conversation. She never talked of sex. Especially not with me. She said, I put everything in a book. Agreed. But what was worse? The truth? Or my imagination. What I know for sure, rapture for her: a library, record, symphony, ecstasy, opera in the park. Intimate pleasure, books, Friday. Terkel, Chomsky. Herculean brilliant, men. Unlike the man who shared her bed who favored "Sábado Gigante" to Sebastião Salgado. And yet, father spoiled her. His Mexican empress. Parícutin tempestuous. Clueless to what she craved. Her red flare sent up weekends "Help. There's no intelligent life around here." Evenings in the blue moon beam of TV. Father mesmerized by Mexican thick thighed floozies. Mother's word, not mine. Shaking their hoochie coochies. Father never drank, ran off, split flesh, brought home each faithful Friday a paycheck. Why would she complain? She lived alone in a house full of lives by the time I knew her. Snake bitter. Mingey. Dead before being born. A woman in formaldehyde."

DAISY HERNÁNDEZ: That was another poem where I found myself just catching my breath. Especially as you you turned you turned it to like what her pleasures were. Books and opera and the arts. Because your sense of pleasure through this book also comes back to books and to the arts.

SANDRA CISNEROS: Thanks to my mom and all of her children love the museums. And we have library cards. And I had a library card before I could hold a pencil, you know, so it was a big change. My my mom, you know, we grew up in the poorest neighborhoods, but my mom enriched our lives with her love and yearning to be an artist. She wanted to be the artist. And she opened the path and was very bitter at the end of her life that she didn't reach her dreams, but she didn't see what she did. She only saw what she didn't do. And I'm so grateful to my mom for allowing me to grow up. And I don't know how to do the things that my neighbors know how to do. I don't know how to make tortillas, and I don't know what it is to put diapers on my little brothers. My mother always allowed me the privilege to stay in my room if I had a book in my hand, even when she needed me. Later on, after cooking, I would do the cleanup. But she respected that time. And that's very rare for mothers in the barrio to do that.

DAISY HERNÁNDEZ: I had the same experience. And it is

SANDRA CISNEROS: You did?

DAISY HERNÁNDEZ: Yes, I did. So I don't know how to cook, but I don't do any of that. But I can write a book. Yeah, I had the same experience a very you know, I think we come to a pretty well even at that age, I knew that sacrifices were being made so that I could have a very different life in certain ways. There is there's so much sexy in this book, but there's also a lot of spirituality. There's so much spirituality through this poem, and there's this poetry book. And several of the poems are in the shape of what I would say, prayers. Yeah. And the last time we spoke was for the Buddhist magazine Tricycle. And I was reading when I was reading the book again, I was so enamored by these moments with the natural world. And it really, you know, you talk about the the little ants who teach you the lessons and nonviolent persuasion by moving you out of the bathroom.

SANDRA CISNEROS: Yeah every winter they they move into my shower and I don't want to kill them. So I have to take a bath, you know, and they do this with you nonviolently. I'm so impressed by what they do. So they're all over my house. You know, in my kitchen, we have a law. We can't kill the insects. If there's a cockroach, I take it in a Kleenex and I parachute it outside. You know, nothing gets killed. We're Buddhists, we're both Buddhists. And I think the the great book that changed me was Being Peace by Thich Nhat Hanh, which really revolutionized, you know, Buddhism. And but it revolutionized me and my way of dealing with the world and dealing with my activism and dealing with my brothers and my mother and, you know, the gurus of your life that make life a little strenuous, you know? But I learned a lot. And I'm so grateful because I always wanted to be in those magazines that you see at Whole Foods by the register, and I always wanted to be in one of them.

DAISY HERNÁNDEZ: And she is!

SANDRA CISNEROS: So thank you so much for doing that work of interviewing me.DAISY HERNÁNDEZ: Can you talk to us about some of these poems? I'm thinking about the poem El Hombre.

SANDRA CISNEROS: Oh, yeah.

DAISY HERNÁNDEZ: Which is very, very intense. I don't know that you necessarily I don't know if you want to read it, but maybe that.SANDRA CISNEROS: Yeah yeah I can read it. But you have to help me. Can you help me? Okay, I'm going to do it now.

DAISY HERNÁNDEZ: This is a real treat.

SANDRA CISNEROS: And you it's a poem where it has a stanza that you, the the the audience have to help me with.

DAISY HERNÁNDEZ: Audience participation. I love it. Thank you.

SANDRA CISNEROS: I wrote this poem as a commission, and if you ever been commissioned to write anything, it's hard, but make it 20 times harder if it's a poem because you don't know if a poem is going to turn out, you don't know what a poem is going to be about. It's like being a magician and people are saying, Pull a rabbit out of the hat and you dig in there and you bring out an iguana. Oh, you know, you don't know what you're going to get when you write poetry. As I said, if you know what you are going to pull out of the hat, then write an essay or a story. So I was commissioned and I remember saying, uh oh, all right. So it took me a while. And this is the painting that they commissioned is a Rufino Tamayo painting, and it's called El Hombre. So I live in Mexico now. I live in San Miguel de Allende. And I have to I witness a lot of things. You know, you just like you in Chicago, are witnessing incredible homelessness and the refugee situation at the police station. We are bearing witness. And what do you do with that? You know, you have to you can weep or you can go to sleep and forget about it, or you can write a poem. “El Hombre.” And what I'm going to do is read the chorus and it's like this: mándanos luz and you're going to say the translation: send us all light. So we can practice. Mándanos luz.

AUDIENCE: Send us all light.

SANDRA CISNEROS: Thank you. “El Hombre,” after Tamayo. "On the eve of International Women's Day. In a field on the road to Salalah, they find her body, the deaf mute girl who walked her dog in Parque Juarez. No one tried. Blamed. Named. The town knows: it's her father's debts. This is how they pay un hombre who can't pay. Mándanos luz.

AUDIENCE: Send us all light.

SANDRA CISNEROS: In small print in the back pages of today's paper I read this small news un hombre Purépecha lifted from his Purépecha village. Daily the Purépechas demand his return, daily el hombre does not return. He is only one of many lifted when you are a native in your native land. To whom do you demand? Who listens? Mándanos luz.AUDIENCE: Send us all light.

SANDRA CISNEROS: The bird merchant at the Tuesday Mercado. Six pages of Cenzontles strapped on his back shoves a mesh shopping bag so close to my face I have to step back to see a flutter of frightened canaries. In the eyes of el hombre the same urgency, the same fear. Mándanos luz.

AUDIENCE: Send us all light.

SANDRA CISNEROS: The gringo Alan tells me the story of the pig who thought he was a dog. Solo vino, he was called because he came alone. How each day Alan drove along the road to Dolores the dogs would run from the squatter's shack and give chase. The pig who thought he was a dog trotting behind them. Until one day the pig isn't there. The dogs disappeared too one by one by one. Alan shrugs. When un hombre is hungry there is no one to blame. Mándanos luz.

AUDIENCE: Send us all light.

SANDRA CISNEROS: The religion section of our Guanajuato newspaper features an article on Saint Francis. Un hombre of austerity as a model for all to live in poverty. This in a country where almost every hombre, mujer, y niño is already on the path to sainthood. Mándanos luz.

AUDIENCE: Send us all light.

SANDRA CISNEROS: How it happened was like this. One night Rosana catches un hombre breaking into her grocery store. The son of a neighbor, her shouts wake the barrio. They're able to hold the thief until the police arrive. Rosana is there to bear witness at the court proceeding and to witness the court set him free. She gathers her pain in a handkerchief, goes home and calls the boy's mother. Rosana and the mother of the thief. Each woman lets loose a sea of grief. When she tells me this story the sea is still there in Rosana's eyes. Mándanos luz.AUDIENCE: Send us all light.

SANDRA CISNEROS: Carlos and Raúl, the silver tongued poets of Chicano, Illinois, have never been to the country of their ancestry, though they're silver-haired hombres. When I invite them south they refuse. They are afraid of bad hombres. No one has told them. The ones who buy drugs and sell arms to those bad hombres are U.S. citizens. Mándanos luz.AUDIENCE: Send us all light.

SANDRA CISNEROS: The blind harmonica player, un hombre who plays Camino de Guanajuato front of Banco Santander, clutches his baseball cap of small coins whenever he hears someone running too close. 'No vale nada la vida. La vida no vale nada.' Life's worth nothing. Nothing is what life's worth. Mándanos luz.

AUDIENCE: Send us all light.

SANDRA CISNEROS: Un hombre tells me, You don't even have to learn Spanish to live here. Amado de San Miguel realtor. You can train your staff to do what you need. And you don't have to pay them much either. Mándanos luz.

AUDIENCE: Send us all light.

SANDRA CISNEROS: Dallas, 1953. A seer named Stanley Marcus purchases a mural by Rufino Tamayo to reinforce friendship between Texas and Mexico. This in a time in history when Texas still posts signs on restaurant 'no dogs or Mexicans.' The painting is of un hombre, anchored to the earth, reaching for the heavens, a balance of earth and sky. North and south. Yours and mine. Because the universe is about interconnection. Tamayo calls this painting Man Excelling Himself. Mándanos luz.

AUDIENCE: Send us all light.

SANDRA CISNEROS: Message from Mexico to the United States of America. When we are safe. You are safe. When you are safe. We are safe. Tell this to your politicians. Mándanos luz.

AUDIENCE: Send us all light.SANDRA CISNEROS: There is a Mexican saying 'Hablando se entiende la gente.' Talking to one another, we understand one another. I would add. And listening. We understand even better. Mándanos luz.

AUDIENCE: Send us all light.

SANDRA CISNEROS: Mándanos luz.

AUDIENCE: Send us all light.

SANDRA CISNEROS: Mándanos luz.

AUDIENCE: Send us all light.”

DAISY HERNÁNDEZ: Thank you. I think you've felt the power of that, yes throughout the book.

SANDRA CISNEROS: Can I read one poem for your tía?

DAISY HERNÁNDEZ: Yes, please.

SANDRA CISNEROS: Señora este se lo dedico a usted. En español. Porque, me salió en español. I wrote this poem and it came out in Spanish because now I live in a place where I hear Spanish y y me salió porque vivo en San Miguel de Allende ¿no? Le es claro les natural que y lo escribí en español y lo traduje al inglés. I wrote in Spanish and I translated in English. So I read the two next to each other, but first in Spanish. "Quiero ser maguey en my próxima vida." “Dar cara al sol todo el día. Reventar hijos al aire como una piñata. Ahorrar agua. Brotar una flor con fleco estirándose al cielo. Estirando, estirando al cielo, qué lujo. Quiero pertenecer a estas tierras que existían antes de que el mundo fuera redondo. Picar las nalgas de los que se acercan demasiado. Regalar aguamiel al que se atreve a chupar mi jugo. Y morir de esta comunión. Deshacerse, deshacerme como ceniza. Volver a vivir en la tierra. Violenta. Explotar de la huerta como Parícutin. Volver volver volver a renacer. Morir para siempre ser.” "I Want to Be a Maguey in My Next Life." “Face to the sun all day, burst offspring into the air like a piñata. Store water. Bloom a tasseled flower stretching itself to the sky. Stretching, stretching to the sky, what luxury. I want to belong to these lands that existed before the world was round. Pinch the asses of those who come close to me. Give aguamiel to the one who dare suck my juice. And die from this communion. Dissolve like ash. Return to live on earth. Violent. Detonate from a field like Parícutin. Return, return, return to be reborn. Die to eternally be.” Okay. Gracias, I did a little switch and what I thought I was going to read because of our conversation. So thank you for helping me along. I was going to read the Hokey Pokey poem.

DAISY HERNÁNDEZ: Maybe we can do it after Q&A.

SANDRA CISNEROS: First what I like. I like the questions. So let's hear from you.

AUDIENCE MEMBER 1: Hi, I'm Tanya León-Moreno, and I am an MFA creative student, creative writing student at Columbia College. I'm a career changer. And my question is, what keeps you motivated to keep writing? Because sometimes you know how it is. And we just need that push and motivation.

SANDRA CISNEROS: Okay, everybody hear the question, what keeps you motivated? Because writing is hard. You have to do it by yourself. And then everyone who's near you says, Come out of there. Why do you want to be by yourself? Nobody wants you to be a writer. They all want you to come out and be social. But I just served you soup. Come on, you know. Well, first you have to find your chosen family that isn't knocking on the door and forcing you to. They know what it is to be alone. And they know and love being alone, too. So you need to find your chosen family. And for me, it's been Macondo, the writing organization that I created. When I lived in Chicago. I used to invite a friend to go to a coffee shop where we could nurse a coffee for 2 hours and exchange each other's manuscripts. So that was like one kind of writing circle. And then later on in my living room in Bucktown, I would invite other writers to come together. And slowly, I started creating a chosen family of writers. So you need to have that because they're going to support and recharge you and understand and know what it is to have a hard day at writing and then and then celebrate you when you when you do have an honor. You know, so do that. You also need to recharge with other things besides other writers and, you know, find the wisest oldest tree and sit underneath it. And you can cry there because the oldest tree knows things that people don't know. You know, it's older than people. In Taipei. I went to a tea shop where the most expensive tea is the old tree. So I thought, wow, I never thought about that, that the oldest tree has the most expensive tea leaves. So I know, I know like, if I feel bad, I just find the oldest tree and sit next to it and I feel so much better. You can also put some some pieces of grass or rock or flowers next to your bed and just be in touch with nature. It's hard to do sometimes, but we live very connected. Get off of the phone and the computer and give yourself a limpia. Get a date when you really give yourself a limpia. The sky is free and the clouds are always trying to get our attention. So focus on that. And you have the ocean, which is the best therapy I know right here. This lake disguised as an ocean. I was told by my driver today that some students in the West Side called it the ocean. And it is like the ocean and it's so wonderful if you live close to it. But I think animals and and if you have an animal and spend time with that animal, if you don't have one, borrow one. You're not. It's so wonderful to sleep with an animal. You know, I think that's so great. You know, I sleep with, too. And I, I always wind up at the edge of the bed, but I get up when I go to the bathroom, go around, and then they roll this way. How sweet. And they're very non-judgmental. They're like, better than human beings. We shouldn't call people dogs. We should call dogs when they misbehave, humans. Right. Because they're so sweet and unconditional love if they haven't been abused. And I just feel like, you know, animals and the clouds and the sky is free, you just need to look up and stop looking down. And, you know, you know, pay attention to those things. Small things of nature. Give gratitude and read people like Being Peace by Thich Nhat Hanh, to make us understand, to look at the world like poets and to get recharged. You are a poet. Are you a poet? Okay. Okay. Write poetry. Poetry's very. Read poetry that makes you run for your pen. Read poetry that makes you write poetry. That'll make you feel so good. Okay. I promise.

DAISY HERNÁNDEZ: And I'll say this for you and anyone else. Email me, because I'm in Chicago now, and I would love to create some writing workshops so you can find me on the Northwestern website but yeah. Daisy Hernández.

AUDIENCE MEMBER 2: Hola my name's Argelia Martinez . I love that question because I wanted to know about how you prepare to write. I think you shared a lot of good advice. My question is, so someone that's first generation Latina born and raised in Chicago, had the privilege to go to Mexico because my parents are very connected to the land and mi abuelito who's still alive. And for someone that's 40, like hearing you say, maguey made my heart sing, because that is that is exactly what I'm trying to do, is reclaim what I'm learning with those experiences. So what would be your advice for someone who has this experience as 40? That is someone like I'm trying to reclaim words and stories as a first gen who was taught to come up in like corporate and like marketing and whatnot. But I'm my soul is shifting. Like it's shifting to tell stories and to share my own experience of releasing what was told of what succession means. And I'm allowing this time to be able to like, help with that journey. So I feel like I have so much to give. But knowing where you are now in life and living and in Mexico, I think as someone that is hearing you speak and just wanted your advice as someone who's 40 and identifies in your experience.

SANDRA CISNEROS: Okay. Thank you for that question and and 40's very empowering. I think every decade for us as human beings, it's empowering because we can see ourselves from a I like how in Spanish you say from esta altura - from this height - when you get to be older because you can see your life and understand yourself better. But one of the things I would recommend very much is to travel. You know, if you can't travel to the country of your ancestors, then travel there in a book, do your investigation, and you're going to have to look in the rubble and footnotes, because a lot of times our history is found in the footnotes and search for. So I believe we have to travel to other lands and it's going to help you so much to find yourself and your voice and your language and the words and inspire you. And the best thing I did was buy myself a one way ticket when I was 28 with my first NEA grant, I was able to finish House on Mango Street 40 years ago. Thanks to that grant and travel to Greece and all over Europe. But I really wanted to travel to Argentina and go all the way to Patagonia, and I haven't done that yet, but I have traveled. And the more I travel, the more I know about myself. You know, even if you go to someplace that's not like your culture, like China, you know, they all look like us. You know, the Chinese people revere jade and they are they know that ghosts exists just like Mexicans. We don't have faith, we know. And, you know, and they revere ancestors. There's a lot of parallels in our culture. So everywhere I went, I would say, Oh, just like us. And it made me love that culture more. So I think the more we travel, the more we see ourselves, the more we love other cultures. And I think that, you know, Mark Twain was right. The antidote to bigotry is travel.

AUDIENCE MEMBER 3: I’m [unknown] and I just turned 80.SANDRA CISNEROS: Brava brava!

AUDIENCE MEMBER 3: But I'm ready to keep on going. But I want to thank you, especially for your acknowledgment of the role that libraries played in your life. I came from Puerto Rico when I was eight, living in a tenement in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, and the library was heaven, and the librarians were fairies, fairy godmothers. And so the whole idea of traveling, if you can travel to Greece or China, there you have it in the library. So I'd like for you to say a little bit more about that, because I think books open up so much. I just published my first book. I'm going to give it to you when I when you sign yours for me, I'm going to give you a copy. And it was it was just it was just translated into Spanish from English. And I have my translator right here for Julia Oliver, who is a professor here at Northwestern. So I'm very excited about her progress. And of course, at 80, I'm very pleased to be starting a new life.

SANDRA CISNEROS: Wow. Brava. Brava. And thank you for giving a shout out to the translators because that is such hard work and usually they don't even get their name on the cover. So thank you.

AUDIENCE MEMBER 4: My name is [unknown] and currently we are reading your book in Truman College, city college, and "The House on Mango Street." The stories resonate with me. I am not Mexican. I am not American. I am from [unknown]. And I was thinking, How does she know about me? And my question is, what advice would you give for the young woman in my generation who has a lot of shame, guilt and insecurities and have children and that they don't know yet where they are going in this materialistic society? Like, what advice would you give for us? Thank you.SANDRA CISNEROS: I think you need to write. And you know, I'm going to say to write an artist would say paint, a dancer would say dance. But I'm a writer, so I know my path. And I think if you write, you don't have to write poetry. But poetry to me is the hardest of all the genres. It's like ballet. If you want to do jazz dancing, you have to learn ballet first. If you want to do any beautiful writing, you have to begin with poetry and you need to read poetry and you need to read poetry that makes you feel like writing. I can't tell you these are my favorite because they might not work for you. Every book is medicine and you have to find the right prescription. So the library is a pharmacy. That's why we can't ban them. We need to have that pharmacy full, right? We need to find the right one that's here for you.

DAISY HERNÁNDEZ: Thank you so much. I think we're out of time.

SANDRA CISNEROS: Yeah. I want to say, if you didn't get to ask your question, don't grieve. I answer all my mail on my website. You can write to me. There's a place you can connect. I answer all my mail, takes me a little while, but I do get to it. And I also have an Instagram and there're very cute pictures of my dogs on there, though I usually put the book I'm reading with a dog because I get more likes that way.

DAISY HERNÁNDEZ: Sandra. Muchas muchas gracias.

SANDRA CISNEROS: Thank you for coming out.

DAISY HERNÁNDEZ: Muchas muchas gracias. Thank you so much.

[Audience applause]

[Theme music plays]

ALISA ROSENTHAL: That was Sandra Cisneros with Daisy Hernández at the Chicago Humanities Fall Festival in 2023.

To learn more about these wonderful authors, head to chicagohumanities.org or check the show notes for more information. If you want to catch your favorite speaker the next time they're in town, you can sign up for our email list to be the first to know who’s where and what’s going on. We’ve got special perks for members too - our Spring 2024 events go on early presale just to members March 12th, so you can secure tickets before events sell out - it’s been known to happen before our general public on sale day, which is March 14th.

Chicago Humanities Tapes is produced and hosted by me, Alisa Rosenthal, with assistance from the hardworking team at Chicago Humanities who are producing these live events and making them sound fantastic. Next up for the Tapes, MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow, for a well-researched, heartbreaking, and ultimately optimistic conversation that you’re not going to want to miss. We’ll be back in your podcast feeds with this episode in two weeks, but in the meantime, stay human.

[Theme music plays]

[Cassette player clicks closed]

SHOW NOTES

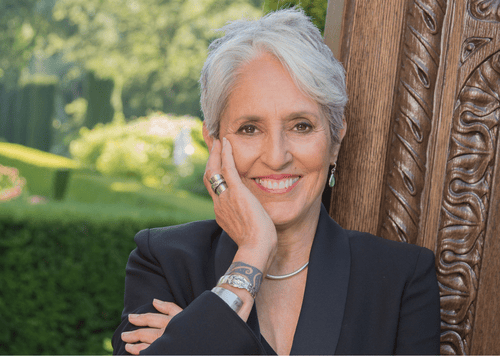

Sandra Cisneros author photo. Photo credit Alan Goldfarb.

Sandra Cisneros, Woman Without Shame/Mujer sin vergüenza

Books by Daisy Hernández

Macondo Writers Workshop

Recommended Listening

- Podcast

- March 19, 2024

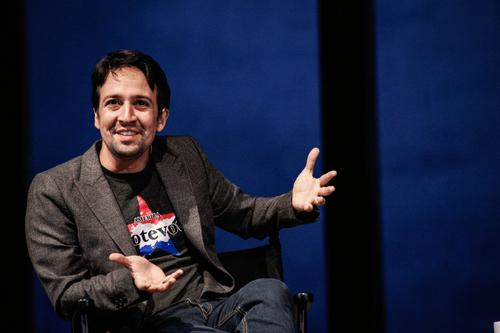

Lin-Manuel Miranda Shares the Secrets to Making Great Art

- Podcast

- July 11, 2023

Joan Baez on Music, Art, and Lifelong Activism

- Podcast

- April 30, 2024

Mini Tapes: Guidance from the Afterlife

Become a Member

Being a member of the Chicago Humanities Festival is especially meaningful during this unprecedented and challenging time. Your support keeps CHF alive as we adapt to our new digital format, and ensures our programming is free, accessible, and open to anyone online.

Make a Donation

Member and donor support drives 100% of our free digital programming. These inspiring and vital conversations are possible because of people like you. Thank you!