Dream Dinner Party: Andrés, Bayless, Bittman, Voloshyna

S2E6: José Andrés with Mark Bittman, Anna Voloshyna with Rick Bayless

Apple Podcasts • Spotify • Pandora • Overcast • Pocket Casts

Welcome to your dream dinner party guest list, curated from two recent programs: Chef José Andrés interviewed by Mark Bittman, followed by Chef Anna Voloshyna interviewed by Chef Rick Bayless – in two uplifting chats on beans, borscht, and the unifying power of food.

Read the Transcript

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: "Budmo!" That means "let us be" in Ukrainian. We use it instead of cheers. And it means let us be healthy. Let us be together. Let us be celebrating this moment.

JOSÉ ANDRÉS: That's why I always say I don't believe in walls. I believe in longer tables.

[Audience applause]

[Theme music starts]

[Cassette player clicks open]

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Hey what’s going on - thanks for tuning into Chicago Humanities Tapes - the audio arm of the live Chicago Humanities Spring and Fall Festivals. I know you’re like, “you sure are saying the word ‘humanities’ a lot, and I think I know what that means? But tell me again to be sure” and it means we bring you the best in arts, culture, science, technology, literature, and politics. It’s like school but you like all the classes and Jason P. isn’t there to make fun of your hair. Head to chicagohumanities.org to check out information on previous programs and to sign up for our email list to be the first to know about our next batch of expert speakers and see them live in Chicago.

I’m Alisa Rosenthal, and I’m continuing my mission to find the answers to humanity’s biggest questions by digging through our thirty plus year archive and our recent sold out events. Today’s episode draws from two such recent events, direct from Fall 2023. First up, chef José Andrés interviewed by Mark Bittman, followed by Anna Voloshyna interviewed by Rick Bayless.

Talk about a dream dinner party guestlist.

Needless to say, you have an incredible episode ahead of you. When times are hard, how can food unite us? Between the humanitarian efforts of the chefs in the following programs and the excitement for life and food they all bring, today’s program is a palette cleansing appetizer, an invigorating main course, and faith-in-humanity-restoring dessert.

Part 1: Chef José Andrés and renowned food journalist Mark Bittman. José Andrés was born in Spain, and immigrated to the US in 1991. He co-founded a group of acclaimed restaurants and established World Central Kitchen in 2010 - an organization that goes into communities that have experienced a disaster, and not only cooks and provides food for them, but also sets them up to feed their community once World Central Kitchen leaves. Check out his book “The World Central Kitchen Cookbook: Feeding Humanity, Feeding Hope” for inspiring stories and recipes - I’ve linked to it, and all the other books mentioned, in the show notes. His acclaimed restaurants are throughout the country and the world - and be sure to check out Jaleo and Bazaar Meat by José Andrés right here in Chicago.

Mark Bittman is known for the “How to Cook Everything” series, his work in global food culture and policy, and for being the long running food writer for the New York Times. Make sure to pick up a copy of “The Best American Food Writing 2023” which he curated this year.

[Theme music plays]

[Audience applause]

JOSÉ ANDRÉS: We are not cooking tonight. So I hope you will not be disappointed. No. Hi, Mark. Are we talking in English?

MARK BITTMAN: We have a chronological question and answer here. So we've known each other. It's more than 20 years. Yeah. And when we met, you were. Actually, you were 30. You're energetic. You were already pretty iconoclastic. You were clearly destined to do things that were more interesting than opening a couple of great restaurants, which is what you started by doing. You were inspired and affiliated with the mad genius Ferran Adrià at the beginning, and I say that affectionately, of course, but I don't think a lot of us know about your early life and what drew you to food, and especially to creative food. So can you tell me something about that?

JOSÉ ANDRÉS: Yes, Mark, I mean. I mean, number one, I mean, because this is like very raw, like we're right here. He asked me a question and then like, you don't know how fascinating is for me. To be here with all of you in Chicago. In a city I came first time almost 30 years ago. And I didn't know anyone to interview by by a man who I knew who this man was. Because who he was in the food world. And now being here with restaurants in Chicago, with many people in the audience now, like old friends being next to these men. For me. It's giving me the chills. So thank you to you, Mark. Thank you for all of you and and my life probably no any different than every one of your lives. At the end, all our lives in magical ways are the same. On. And they realized that I became who I became. Probably you will agree with me on who you are becoming. Who you are. Thanks to the people that always was around us. Every moment of our lives. Even people we forgot. But that nonetheless were important in who we became. I have plenty of those people in my life that they invested. Their time, their effort, their love. In making me who I am. And this goes for everyone of you. And I hope, Yeah, you can clap. We don't charge for clapping, at the Humanities Festival

[One audience member laughs]

JOSÉ ANDRÉS: She’s my type of person. And for me, I never had. The best relationship with my mom or my dad. Not to their fault or to my fault. I believe life. You know, when sometimes you realize that nothing comes with instructions. You tell me when I became a father and I'm looking like they're my wife giving the baby. Where are the instructions of the baby crying in my arms? I'm like, How? How do I handle this thing? But is the same to becoming a husband or wife? In my case, a husband, but the same becoming a boyfriend or the same becoming yourself a boy or or becoming a chef. But in a way, with what I tell you, with the relationship with my family at the end, I am everything I am because I had a fascinating woman. That's enough. As a mother and a fascinating man as a father. That they were not perfect. But I realize I'm not perfect either. But they had amazing things that made everybody around them always feel welcome. And my mom was a very early influence in my life, including Mark. In a way that now I'm realizing what that influence was. Which my mom was a nurse. My mom became a nurse pregnant of my fourth brother because she had to bring a new salary home to be able to pay the bills. Pregnant of my fourth brother and been a mom working mom at home. She carried the family forward, became a nurse at Standing Heart. My mom was really and on top of that, Monday through Friday, she will be the one in charge of feeding people. My brothers and I, my father was more the weekend. Everybody helped though. And my mom at the end of the month. When was never anything left in the fridge. It looked like if you went to Best Buy to buy a fridge and you open. Oh, so beautiful. Empty. That was the commercial of my mom. But she will always find the half egg that was boiled dry, that the poor egg was almost with a signal there saying, Please save me the little piece of dry chicken from the roasted chicken from two weeks before that is still was there saying, what is going on? Please eat me away and she will get the chicken and the egg and she'll chop it and she'll make a béchamel with flour and and milk and she will add all this chop whatever leftovers were in the kitchen, and she'll make croquetas that she'll roll in the bread crumbs of the old bread of the last month using the coffee grinder. And I can believe right now, today, those croquettes that came from my brothers and I. A message of love. Home. Any time I went back. What do you want, croquetas? I can't believe I'm charging people now for croquetas now. So this in a way, was very important for me on top of my father, the weekend cook inviting everybody. Never keep in a a list of who he invited, then said yes, meaning ten people could come or 40 because my father was very generous in feeding the many. And my mom would be always. Come on. What happens if everybody comes? My father always said big problems have simple solutions. If more people come, we add more rice to the paella pan. So you see, between my mom maximizing the power of feeding a family almost with nothing. And the power of my father used to take any problem in a very relaxed way, but nonetheless always been, you know, in a strange way, successful. This early on was more important in my life than I realize, even until recently. And that was, in a way, my early culinary days.

[Applause]

MARK BITTMAN: Nice story.

JOSÉ ANDRÉS: I have other stories, but I'm going to leave them at that.

MARK BITTMAN: Before we started talking about World Central Kitchen, which is probably what most people here want to hear about. I thought I might give you an opportunity to talk about another important thing from a few years ago called DC Central Kitchen, which tracks very nicely with how you've started and where we're going.

JOSÉ ANDRÉS: Well. Again, he's asking me that question, but he knows the answer. Not not under my perspective, but under his perspective, because he's been part of that organization or other organizations in New York and across America. But. DC Central Kitchen became a very important part of my life. For the ones of, you know, I was in the Spanish Navy. And I was cooking for the admiral and I was like, really? I am in this Spanish navy and I have to cook for the admiral in his house. I want to go in a boat. I knock on the door. When everybody told me I couldn't tell the admiral anything and I didn't tell him anything. I only tell him wouldn't be nice. That you that enjoy my cooking so much that other sailors will be able to enjoy the same cooking you are enjoying. This was a way for me to tell him. I'm very happy to cook for you, but I want to go in a boat. I went on a boat and I traveled the world. And first time I visit Africa. First time I was in Latin America and the Caribbean. But for me was the first time I visit the United States. I came to a city called Pensacola. A city that was celebrating the Five Flags. You need to understand the ship I was on was not 90. Ship was the ship full mast. Beautiful white boat. Sailing tall ship boat, but like a movie. Arriving to Pensacola. With their Blue Angels, their Navy planes pilots use flying above the boat. With the white beaches of Pensacola and then realizing that the Five Flags, one of them, with permission of the Native Americans that were there, had any one of those flags. But one of the flags was the Spanish Castilian flag. Like, holy shit, sure, I belong here. I'm sorry. We. Well, I'm Catholic. You know, Sundays we ask for forgiveness and boom. So I'm only a few hours a sinner that's all. But I'm telling a story because for me it was important because it was the moment of belonging. You know, yes, we are rife. With permission of the Native Americans and the Vikings. We arrived like almost a hundred years before the British. Sorry, but this true. Yeah. And when we arrive, the food is always much better than anywhere the British arrive. I mean, this is off the record, but it's true. Everybody knows it. But this was an important moment in my life because it was the moment I understood. I arrived in New York, Lady Liberty, Ellis Island. And as a mom and dad watching that Lady Liberty with what it's all about. I'm watching Ellis Island, understanding the meaning of Ellis Island. For immigrants like me, that I've even thought about coming back to America. But everything began in a way, creating the DNA inside me. Of I want to be part of this without realizing. I finished the military service. I came back in case there's an immigration officer in the house, I came with a Visa, legal. This happens sometimes. And I came back to New York. I became a cook in New York before realizing, I landed in 1993 in Washington, D.C. I opened my first restaurant with, we are celebrating 30 years this year, hallelu, which now we have one in. And long story short. I realize that restaurants like mine are really important to great communities because people like you join us and we all create a place to all of us to belong. We create community. But very quickly, I understood that in restaurants like mine that we feed the few. We wouldn't really be successful if we then were part of other organizations that were in the business of feeding the many. And this is when this is Central Kitchen came into my life. I began volunteering. This is an organization that does amazing things. More than 35 years open founded by a guy called Robert Egger, a guy that was a bartender. And the guy that saw that we were wasting food. So he was ahead of anybody talking about wasting food, but he was ahead of everything else in the sense of when we waste food, we don't really waste food. What we do is we waste people's lives. And this guy told me that I was 23, 24. That philanthropy seems is always about the redemption of the giver. When philanthropy must be about the liberation of the receiver. And in that place, the same lessons that my mom was teaching me on making croquetas with nothing. I began sharing that same knowledge to men and woman that this is Central Kitchen was ringing coming out of the streets. People that were homeless. American born, Washingtonians. But somehow they didn't belong to a city. Me being an immigrant, I already was kind of belonging in a way more than them. What? Least I was experiencing a better life than all of them. This organization began taking people out of the streets, out of coming out of jail, training them to be cooks, paying farmers that they were allowed to throw food away. But somehow making some money out of food was about to be wasted. Bringing the food, bringing the people bringing a very powerful idea. Let's then feed the homeless of the city, all with $1. $1 to give hope to people. $1 to train people. $1 to rescue food is about to thrown away. $1 then to find them jobs in restaurants like mine. And there I am. Not only sharing my knowledge next to hundreds of other chefs in the city. But in the process, those men and women were also teaching us lessons about the meaning of belonging, not like they were in the street and men, they felt they belonged less. They only were never given the same opportunity I was given. That organization changed my life because in a way, show me the power of food to really stop throwing money at the problem. Stop giving the crumbs to the hungry, but actually investing in true solutions that in a fascinating way has shaped what Washington, D.C. is still with the problems we may have. Where we were all part of the community was not ours versus them was, again, we the people together trying to solve the problem. One plate of food at a time. That's what D.C. Central Kitchen did for me.

MARK BITTMAN: I realize now I don't have to actually ask questions. I could just say like one word. But seriously, let's let's let's move on to World Central Kitchen, which is I mean, I do know this story. It's true, but not everybody here knows this story. And the beginning of World Central Kitchen is another fascinating tale.

JOSÉ ANDRÉS: So so the beginning of the story is not really the moment we began with what Central Kitchen but came way before. Came in moments like when I read John Steinbeck. And I understood The Grapes of Wrath that even in the richest country in the world seems was a love inequality. Reading The Pearl. I mean, I love John Steinbeck. He's quick, short. I understood his English and I felt like, Yeah. Um. Moments like when I was in the military service in that old ship going to Rio de Janeiro, to Abidjan, Ivory, Ivory Coast. And seeing that while maybe there was also poverty in Barcelona, the city grew up, I never saw what I saw in Ivory Coast, in Abidjan or in the favelas in Rio de Janeiro. Or outside the Dominican Republic. And that began also as a young boy, kind of. Wow. Even in the places I think there may not be hunger here. We have people that are going through obviously, all of that had a lot to do with my involvement with this Central Kitchen. But then slowly but surely, certain things began happening. Obviously the lessons learned in this interrogation. I became the chairman of the organization of the board. I'm still very involved with that organization to this day. But they began seeing that things were happening and food and water was an afterthought. And I always thought that is a universal human right that should be food and water should be available to all. Maybe because I was a young Catholic boy that, you know, religion class obviously becoming a cook for me. Jesus were like the coolest, right? This guy, you'll give him some fish and some bread and the guy feeds everybody. I mean, we're all over in the restaurant business if we have many guys like him. Yeah, but it's true. But in a way, I remember watching Katrina. New Orleans. Poor communities in the low nine forgotten. Tens of thousands of Americans in a way, in a very big catastrophe forgotten. But even if we then took care of everybody, was those moments that are very big in my mind. When thousands of Americans went into the Superdome. An arena. An arena that. If you think about it. It took days, if not over a week, to bring food and water to the people in that arena. Things were terrible. Things were happening inside that arena. You know what an arena and a stadium is. If I ask you, everybody will say, Yeah, he's where I go to see my NFL team or my NBA team or my favorite musician. But everybody's wrong. An arena a stadium is a gigantic restaurant that entertains with a sports and music. When they go to the baseball stadium, everybody is eating hot dogs. I don't see anybody watching the game. Nobody seems to be able to hit the ball, God's sake. And that moment for me, I watch in the comfort of my home in action. And these are the women that. I began really thinking, Oh my God, can we do more? Then we saw September 11 in New York, random, fascinating moments of citizens that were trying to help by us putting a grill outside the restaurant or use by opening the doors and making some meals to anybody that will need a meal. Not an organized effort, but random, powerful efforts of empathy. So we now began putting all these in my brain. I'm like, Wow. I think my profession that we feed the few, we can feed the many. If we all come together. For me, it was very important. 1996, 97, one across the street of my restaurant Jaleo. Brick. A red brick building. Was kind of reopened because they were doing construction and they found their belongings of a person. Seems the belongings of a person that had somehow her office and her bedroom. And that's the woman that worked during the Civil War in the front hospitals. The hospital's behind the front lines taking care of the wounded. And this is the woman that created the missing soldiers office when the Civil War ended trying to bring home. Closing to the families that lost loved ones in that Civil War. And the woman that created the Red Cross in America. The woman was Clara Barton, a nurse nonetheless, like my mum. A woman that put at the service of others, that she could be killed in the field. But she decided to create organizations that she could be healing the many. In emergencies or in any situation. If you have to stop a fire, you send firefighters, I began thinking. If you have destruction in an earthquake, you send search and rescue teams. If you need to heal the wounded, you send nurses and doctors. But if you have to feed people in an emergency, who do you think would be the best prepared people? We. That's in Bolivia. I was in Cayman Islands with those moments of inaction, but only dreaming of what we could do. I still. Watching the people that were feeding around the world in difficult circumstances through U.N., World Food Program and others. Haiti happened in 2010. Destructions. Hundreds of thousands of people die. Hundreds of thousands of people lost their home. And I was watching in Cayman Island in the TV with my friend Eric Ripert. But then Anthony Bourdain. And that moment I said, you know, I'm not going to watch more in the comfort. I'm going to go not to help, but to learn. As soon as I could, few days later, a few weeks later, I got on a plane. I landed. I arrived to Haiti. I began cooking in a couple of camps. And that's the moment my learningship began in home cooks like us. We could be very important in emergency relief. That's how World Central Kitchen began on that early 2010 earthquake. And from there we began dreaming. What else we could do. As the organization slowly began learning and began adding more team members and more volunteers, that was the beginning of World Central Kitchen. [Applause] I was going to go to more stories, but I'm waiting for you to ask me that. Just. It's a question of the next

MARK BITTMAN: We're going to the same place, so. I would ask about I mean, I would ask specifically about Puerto Rico and Ukraine. But there may be other things you want to talk about, but people do want to hear about the work, I'm sure.

JOSÉ ANDRÉS: Yeah, we can. Obviously now the missions are many. That World Central Kitchen has been involved in the last 14 years, very much since we. We created. We began mainly Haiti, we began. In the limbo, in the edge of disaster and development, you know, disaster and use long term humanitarian relief. But very slowly we began responding in the same Haiti to some hurricanes, to some earthquakes, even at that very light scale, too, compared to what we do now. We went yes, from doing few thousands, sometimes even tens of thousands with very little. And when the organization very much was me and one more person, the person running it, then when the funding came used for the money, I was racing through my restaurants. But we began learning and we began doing certain things that I think were very powerful. So many schools in the most remote areas in in Haiti, some changing, some schools from charcoal cooking to clean cooking with gas. A school to cooking school to teach woman how to cook with those cleaner cooking to try to move them away from charcoal. Projects that became important for me because in a way, I was trying to bring to the rest of the world the lessons I learned in DC Central Kitchen. But then. Houston happened. That was Irma, Houston with Irma. And they went there. With a team of few chefs, friends that came with me, and we did a kitchen in the convention center. We help in the convention center. I'm not going to get into dramatic stories that happened there. Um, Children's Hospital. We partner with a couple of schools, one synagogue, a couple of churches, and we began feeding out of those places, not only the people inside Houston, but people out in the surrounding areas. They usually are the people that are always forgotten. And when they finish the mission there, after a couple of weeks right there, ten days later, Maria hits Puerto Rico. Category 5. The hurricane crosses slowly but surely across the middle of the island and whatever we read cannot do justice to the disaster that was unfolding. So I was able to land with with who then become the CEO while the third CEO World Central Kitchen, my friend Nate. And we landed. And in a way, Houston was very important in the shape of what World Central Kitchen became. But then Maria was the moment that we said, that is what we are doing from now on, and we are never going to stop. Which was simple. In. In the worst moments of humanity the best of humanity shows up, like I saw in September 11, right in Manhattan or even in Washington, D.C., when the plane hit the Pentagon. But what people want is to give an opportunity to be able to help. And where the bigger organizations are not keeping you away. Because who is better than the locals to help the locals? Not every local can, because when the hurricane hits, you are in distress. People are looking for family members. People are trying to survive. People are trying to repair the roofs. So it's important that teams come from the outside. But very quickly you see that it's always locals that are willing and able to help. And what we began realizing is that if we could empower those, we have the biggest army of goodness that we could build. So in Puerto Rico, when I arrive, I send a text message not knowing if my friends will be able to read it. WhatsApp with a simple message. I'm coming. Those very simple words from a chef to chefs, means something very important. If you are coming and you're a chef, where're you coming? You still write a book? No. You're coming. You're coming to help. And you're coming to start feeding. I met a chef, which is like my brother called Jose Enrique. Who already was trying to fix his restaurant with a generator, even when he didn't even had any guys with diesel to run it. And in that first day, two days after the hurricane, we were doing 1500 meals, more or less. We went from 1500 meals, to 150,000 meals a day. We went from one kitchen to 34 kitchens. We went we got ten food trucks, that then became 20 all across the island. We were able to empower indirectly as schools to open their kitchens with whatever food they had to feed their communities. At the end, we did almost 4 million meals. And I would say we influence said many more million meals. At the end, what I saw is that cooks, we were the best prepared people to help in an emergency. Why? Because everybody always asked me, José, where do you get the food? Well, in the same place I get it when everything is right. In the food warehouses and the food companies. It's always food around. It's always a restaurant somewhere. It's always people are willing to join forces to start feeding. It's always people willing to drive their four by fours to deliver to remote areas. It's always a helicopter pilot that doesn't know what to do but wants to help, and the only thing you say is join us. We went to Ukraine. Two people. World Central Kitchen. Before we knew it on the first 24 hours we were feeding already in a week we were feeding in every border city in Poland. As Ukrainians were living. Before we realized we were in every country surrounding Ukraine as refugees were living. Before we knew we were elsewhere in Germany and in France. But at the same time, we went inside Ukraine and we were in life and we arrived Kiev when the still the Russian troops were trying to break the defenses of the city. Before we realize we went from again thousand meals the first day to more than 1.5 million meals a day in Ukraine. We've done more than 240 million. And we do that using creativity. Um, using restaurants. More than 500 restaurants join us. We were able to support them because especially American people were always very generous with us. And thanks to that generosity, we were able to put that money in real time at the service of providing relief. Who were feeling. We built two kosher kitchens of people, of Jewish people living in Ukraine. And in the middle of the war, we were feeding churches, we were feeding refugee centers, we were feeding kindergartens that they were trying to use their kindergarten to host as many families as they could. Millions of Ukrainians were living the horrors of war. At the same time, we were feeding in the front lines. In this war we lost in Ukraine six World Central Kitchen volunteers. Out of two missiles hit in the bunker where they were sleeping. We've got few kitchens destroyed. We've got few bakeries. We got many trains destroyed with food. But thank God there was never life in both. At the end of the day, I kept asking myself, Why are we here when we are losing lives? And the question the answer to the question by the fellow Ukrainians we put a team of almost 5000 Ukrainians with World Central Kitchen where every dollar was going used to help pay the restaurant so the restaurants could pay the teams buying the food locally, so the food could help the farmers that at that point nobody was buying food from. In the process of aiding, we were helping the local economy somehow maintain itself. That's the way we do it. Right now we are in Armenia. Worries are another war. We are right now as soon as Hamas did their crazy attack against Israel, we began feeding in Israel. At the same time, we began feeding inside Gaza because we were already there before. And we have a great partner called Anera who they are medical. But because they know Gaza so well. We use their knowhow of Gaza to do what we know, which is food. We were better because they make us better and in the way we make them better. Inside Gaza, we've done close to 1.4 million meals. Even when you are reading that food cannot get in. We are in Jordan. We are in Egypt. We are in Lebanon. Right now we are in Acapulco, in Mexico, after this crazy hurricane, Category 5, with helicopters trying to reach a community that is totally distance from any aid arriving because the harms that this Category 5 has done. I cannot believe that now we are able to be in seven or eight missions at the same time when we are still a very small organization of 8000 people. Why we do that? Because we allow people to help us and we are able to increase the number of people that are part of our organization all the time. And now is the gift that keeps on giving. Communities that we held before. Every time something happens in another country. Usually we have five, ten, 20 people that want to come to help this other country. Why? Because before we were there helping them. So now they are here helping them and them help them. And at the end, when you see community at best, in the worst moments of humanity, the best of humanity shows up. That's unfortunately the beauty of these moments.

[Applause]

MARK BITTMAN: I want to try to do two things. We've had this conversation before, so I know it's safe. But one, it's. But it's but it's not without.

JOSÉ ANDRÉS: Do they have is is any lawyer that can represent me.

MARK BITTMAN: One is to give you an opportunity to talk about the future of World Central Kitchen if you want to do that. But there's a let me just let's just have this little let me give you an opportunity to talk about this. A third of them. Just to talk about the United States. A third of Americans would be completely broke if they had an emergency that costs them more than $400. 10% of homeless people are homeless as a result of natural disasters, hurricanes, earthquakes, etcetera. The work that you're doing is amazing. Everybody here agrees about this. But doesn't it point to a gaping hole in the work that the federal government, etc. ought to be doing?

JOSÉ ANDRÉS: Well. You. You're right about that. I mean, I'm not gonna lie to you if I don't tell you that all of these, and especially the last 14 years, has been, uh. You know, a big burden. On the shoulders of many. Now I'm going to be a little bit selfish, but because you're kind of here listening to us, to me. And this looks like a confession.

MARK BITTMAN: I felt that too.

JOSÉ ANDRÉS: You're a rabbi? In a methodist church, that's cool. But. But, you know. I feel the burden. Right. And the burden sometimes is a way that can be. I am very sure all of you have a burden. And I have a feeling as we grow older, it's part of life. We feel the burden, right? Because we we feel responsible. Responsibilities are genuinely ours. So responsibilities we do take on our own. And I have a feeling we are all here to try to lift up the burden out of each other. And it's okay to recognize, we feel. I don't know. Call it whatever, you need to go to the psychologist or you need to talk to God or you need to talk to your mirror. But I feel that. I feel that burden. But we need to make sure that that burden is not what brings us down, but is a burden that actually lifts us up. To understand that we are not alone. I'm not alone. But I'm surrounded by people that believe like I do, that we can do better if we come together. I saw it when I was in the ship. I said, You're a Navy boy dreaming of an amazing world I wanted to be part of. When we were three hundred crew that doesn't matter where the wind came from or the waves or the currents, because we were working together as one doesn't matter who we were, what religion we were, what even we were all the Spanish people, probably all Christian and Catholic, not necessarily churchgoers, but nonetheless. The distill was 300 people from different parts of life that we work together with one mission to take that boat to safe port. And that's at the end what life needs to be. Call it politics, call it socially, call it government, call it our cities called our families. Why do all we do to make sure that our burden actually becomes the wind behind the sails? What do we all do to make sure that our burden can always be shared so the weight is not so heavy? How can we make that the burden is actually what gives us the purpose to serve. In our families, in our work, in our society, in our community, in our country. We can be finger pointing all day. We want to the problems to everybody else. We can use these same finger and stop finger pointing and say, I'm here. I'm here to join and to serve and to join forces to anybody that like me believe that together we, the people, will always do better. So it's true that sometimes we need to be asking our government. For better at every level, especially in emergencies but - at the end I realized that the government is not them versus us. We are the government. If things are not as we want them to be, let's stop finger pointing at what they are not and let us be the change we want to see.

MARK BITTMAN: Switch gears and talk about the cookbook.

JOSÉ ANDRÉS: How much time, because they said we have a clock. But it’s not it’s a clock.

MARK BITTMAN: It is what time it is. Someone will, someone - don’t worry.

JOSÉ ANDRÉS: No, no worry, because I've been trying to be precise in in the answering because, you know, with my lack, with my lack of English, I use two or three more words to express myself. And then makes it longer.

[Laughter]

MARK BITTMAN: This is you being brief. But let's talk about the cookbook, because it's not a typical cookbook. The Ritz, not a cheffy cookbook. It's not a cookbook without a position. It's a cookbook with a position. It's an unusual book, a beautiful one, as I might add.

JOSÉ ANDRÉS: Well, I mean, coming for you. I mean, I just want to make sure, obviously, you see that my name is in the cover of the book. And that was never my intention. But the contrary is only that. An editorial these days wants also have a name on the cover of the book because somebody has to take ownership of that book. But in a way it's very unfair that my name is in the cover of that book. Because that book and the purpose of why I thought we should be doing this book, you need to understand I'm the founder of World Central Kitchen. But. But not anymore. I used to be the chairman, and now they brought me down to be a board member. And I'm very afraid I'm about to be kicked out of being a board member. And I hope I can keep being a volunteer. But the idea of the book was simple, as you said. This is not a cookbook, but this is a celebration of the people that under the most dire situations were able to do fascinating, magical things. In the middle of darkness. And every one of those recipes are not really recipes. Every one of those recipes are people. That made something happen. Used to feed fellow citizens. Where sometimes we will not have plates or forks. But we will have an amazing group of women that will make tamales. But we didn't even had plates. But they still they will have an open fire that they could be making these masa dough and fill it up with chicken or anything else they got and make these amazing tamales sometimes with banana leaves and some things with core husk. And all of the sudden armies of those women that had those little places that sometimes we don't go because they look too informal and aside. Not even a restaurant shop on the side of the road. I will go. And will go to fancier restaurants. At the end of the day, those are the woman that are feeding the cities and the countries in very remote poor areas around the world. And we will go. Yeah, you can, because who feeds the world is not cooks like guys is really women like my mom and many others. Thank God that women are in charge of feeding the world. If not, the world will be even more hungry. More needs to be done. So we empower them.

But in this book it's the stories of those women that we will be able to deliver tens of thousands of tamales, even when we didn't even had any organization going. But people were hungry. And we are not the organization that likes to plan. We organization likes to adapt. And in this book, you're going to see a lot of adaptation. The urgency of now is yesterday when you talk about food and water. And in that moment, even with without napkins and plates and forks. We could have those thousands of tamales being delivered where you could grab this tamale given with love by one person to another, and you could be using use the leaf to grab the tamale and eat it in a very humble but powerful way. You're going to find many stories like these, like the day I was in Haiti, cooking beans, black beans. I'm from Spain and I was cooking in the way we cook black beans in Spain. But it happens I was in Haiti and people don't want our pity. People want our respect and to give respect so much. To give respect is so easy. I mean, it's so simple. I always want to call President Trump to tell him he's so easy to give respect to fellow citizens. I'm not trying to make a political use realistic and pragmatic. To give respect even with people you don't know or you disagree with. Or even you don't share religion or more, you've seen life. Respect is something so simple to give. Those women were coming to me to tell me thank you for cooking for us and and providing the food and. But hey, man, we. José we, 6 hours cooking and they all come to me and hey, we don't want to be disrespectful, but we don't like the beans the way you cook them. And in that moment I realized the power of listening, not the white boy mentality. This is what you need, people. But the new mentality that we should all believe on on listening to the people that want our help. On that day singing beautiful Haitian songs. It took two more hours, but they made the beans into this amazing puree. We pass them through a sheaf out of some rice sacks of USAID, and at the end they did this amazing, velvety, silky, shiny, beautiful black beans sauce that they love to eat next to the white rice. And if they're lucky, a piece of meat or fish next to it. And to me, that's the moment I understood the power of listening.

Listening to change the world, listening to give dignity. And this is, in a way, something like I know I said story that keeps going through World Central Kitchen. And in a way, this is a book to celebrate those men and woman. To celebrate the thousands and tens of thousands that by now they've been part of working with World Central Kitchen, even if it's only for a day. And in a way, this is a book that they know is going to capture and make more people join our simple efforts well through World Central Kitchen or through new efforts at the grassroot that will happen in every corner of the world. I found the other day a letter from Clara Barton. I don't know if I'm going to be able to buy because is expensive like oh. But is a letter that she was writing to a friend. And she was just wondering and mentioning after she had retired from the American Red Cross, she founded. She was wondering if she was supposed to write a book to make sure that what they achieve at the early days of the Red Cross will forever be remember. I only laugh and I thought about it because in a way, that's what I really try to do with this book and a couple of other books we've been doing to make sure that we share this story for every person that makes World Central Kitchen possible that is far away beyond whatever I did. World Central Kitchen exist because it's an army of people of goodness that they want to be part of the solution. I'm not used to staying home like I did in Katrina. That's why this book exists. And that is why this book that is being written in writing by some good friend who is a great writer, spent hours and hours and days and months listening from the people. Their stories. And in a way, he put. Into the book, the voices of all those people. That you see my name on the cover of the book is deceiving. This is a book of we, the people of every corner around the world where World Central Kitchen has been in action. Is not my book, is a book of the people.

MARK BITTMAN: I'm done.

[Audience applause]

ALISA ROSENTHAL: That was José Andrés with Mark Bittman at the First United Methodist Church at the Chicago Temple at the Chicago Humanities Fall Festival in October 2023.

[Theme music]

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Part 2: Anna Voloshyna and Rick Bayless. Popular blogger and chef Anna Voloshyna was born in southern Ukraine in 1990 - her debut cookbook “Budmo!” is filled with Instagram-worthy creations combining traditional Eastern European recipes with her contemporary touch. Stick around till the end for more information on her humanitarian efforts during this time of crisis.

We’re treated to her being interviewed by Chicago’s own Rick Bayless - acclaimed chef, restaurateur, winner on Bravo's Top Chef Masters, and host of the Daytime Emmy-nominated “Mexico–One Plate at a Time.” Writer of nine cookbooks, if you haven’t yet, you gotta check out his mainstay Chicago spots Frontera Grill and Topolobampo, with many more to choose from. His teaching and learning skills really shine in this conversation, and check the show notes to learn more about this philanthropy through the Frontera Farmer Foundation and Frontera Scholarship.

[Theme music plays]

[Audience applause]

RICK BAYLESS: Hello, everyone.

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: Hello. Hello.

RICK BAYLESS: Well, thank you all so much for coming out. We've got a really lively conversation, I'm going to call it that planned for you this afternoon about a cuisine that may be sort of new to a lot of you, because I will tell you that I was when they asked me to lead this conversation, I was super excited because it's not a cuisine that I know that much about. And when I got a copy of Anna's beautiful book, I was super excited to delve into it. But I think the place that we need to start is certainly what we all hear in the news about Ukraine. We're going to come back to that later on in our conversation. But. Putting it in its geographical place, I think is really important for us to start with because as I was starting to read through this book, all of a sudden I realized that there were a lot of influences in Ukrainian food that I didn't sort of expect. And so we all can relate it to Russian food because that's on one side of Ukraine. But then when you think about that, it borders on the Black Sea and you've got all of those countries around the or around that sea that go down into Bulgaria, in Turkey, and you start in Georgia and you start to see those kind of influences coming in as cuisine. I thought that was a really good place to start. So when you talk about Ukrainian food, how do you describe the the intersection that you find there?

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: So, hi, everybody. I'm so happy to be here. So Ukraine has the most fortunate and the most unfortunate location. We have a lot of neighbors and a lot of those neighbors were great empires once. So Ukraine was conquered and it was teared it apart. And a lot of those cultures left its mark on Ukrainian cuisine. Why we have a fortunate location is because we have two seas in Ukraine, Black Sea and Azov Sea, and we have the most amazing land, the most fertile land, so we can grow anything. You can put a stick, you know, just in the soil and it will just blossom. So that's why we have one of the best produce in the in Europe, and that's why we have so many grains. That builds our culture of culinary culture and our dishes and menus. But again, we have so many countries that tried to conquer Ukraine over these years, and they left left their recipes with us. And we kept the best. I'm promising you and you know, when you travel through Ukraine from east to west, you will see that the culinary culture will change. On the eastern side, it's more Russian, it's more Soviet, I would say. And then you travel and you discover these beautiful canteens, beautiful bakeries. And it's more European in a traditional sense of this world, like beautiful pastries, these coffee shops, everything is so lively and so elegant. So you got the idea. And when you go closer to the sea, you will see the Jewish influence. You will see Turkish influence, because we have once we had Crimea, we had a lot of those flavors there. And hopefully they will come back to Ukraine very soon. And I wanted to celebrate that in "Budmo!" because I wanted to show that Ukrainian cuisine is vibrant, it's fresh, it's comforting, and at the same time, it has all those different elements that can co-exist in Ukraine. It's not just borscht and dumplings. It's so much more.

RICK BAYLESS: But it is borscht and dumplings. Yeah.

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: It is. It is the heart of our cuisine.

RICK BAYLESS: I don't want to disappoint you there, ok. So you mentioned the name of your book. So pronounce it for us so that everybody can hear this.

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: The name is "Budmo!"

RICK BAYLESS: "Budmo." And what does budmo mean?

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: That means "cheers." So, no, that means "let us be" in Ukrainian. But we use it instead of cheers. And it means let us be healthy. Let us be together. Let us be celebrating this moment. And that's one of the most cheerful words in Ukrainian. And that's how I want it to represent this book. This book is about celebration. It's about celebration culture. It's about celebration, family recipes and the community.

RICK BAYLESS: So you mentioned how incredibly fertile the land in in Ukraine is. And I don't think that's just one of those sort of idle boasts, because I think every day on that some newscast, I hear about the fact that a lot of this stuff that is grown in Ukraine can't get out or that people are not growing it because of one thing or another. And so it led me to go and investigate the the amount that Ukraine produces. And I will tell you that before we started hearing Ukraine in the news every day, I never would have told you that Ukraine produced as much, what are the main things that are produced in Ukraine?

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: A lot of grains.

RICK BAYLESS: A lot of grains.

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: So much, lots and lots of that. So it's mostly wheat. We also produce corn, which was brought to us by food shop from the United States and lots of sunflowers. We have the most beautiful sunflower fields and we produce a lot of sunflower oil. And I used to go to Trader Joe's and just pick a bottle, just turn it and "made in Ukraine."

RICK BAYLESS: Made in Ukraine.

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: Not anymore. Now it's Mexico because we can not export that much right now. And we lost a lot of our fields and half of them are mined. Half of them are under occupation. So it's it's very unfortunate.

RICK BAYLESS: But that whole thing about sunflower oil really surprised me a lot. And I have this wonderful opportunity to be in the southern part of France during the sunflower harvest. And it was really beautiful. And so I was curious and I thought, I wonder if France produces the greatest amount of sunflower oil. But of course, no, it was Ukraine that does and I can't even imagine how beautiful it must be during the sunflower harvest in Ukraine. And well, we'll just hope that that will all come back.

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: Oh, so I won't surprise you. It's not that beautiful. It's not. I just came back from Ukraine, and the only thing I had in my head is I need this photo of a sunflower field. And I am standing there having my best fashion moment. And it came there and the sunflower fields were getting to get harvested and how they harvest them, they let them dry right on the stalk. So it's basically all dark and all the gloomy and everything is dry. And I'm like, Oh my God, this is what I get. Like no sunflower field photo. And then we traveled all over Ukraine, we haven't found even one. And then we were going to my hometown and in the middle of nowhere we found that one sunflower field there was blooming. It was beautiful. I don't know which crazy person planted it because it was so out of season and I got my photo.

RICK BAYLESS: Well, I'm glad to hear that you haven't sort of like encouraged me to go to Ukraine during the sunflower harvest now but. I told you that I'm cooking a big meal out of this book on Monday night. But the one that I settled on was the eggplant caviar, because it's got things like fenugreek in it, which are a spice that I absolutely love. So tell us about what roll all of those dips and and snacky things play in Ukrainian cuisine.

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: Oh, they play a big role.

RICK BAYLESS: That's what I thought.

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: Basically, they are always on the table just to add some flavoring, something pickled, something tangy, because we have a lot of heavy dishes, comforting dishes with potatoes and meat and like you always have potato and meat on the table, but you need to bring back to life somehow. And by using these wonderful spreads and the condiments, you just add the flavor. And I love that eggplant caviar, especially because this is the southern dish. And it's something that you will see on everybody's table during summer and fall. And when I went back home, I my mom made it for me. And when I went to cook at the frontline for our soldiers, this is what I made because I wanted to bring a southern dish because I was not able to come to the South before I went to the frontline. And I was gathering all the ingredients from my trip to bring to them and cook with them. And I'm like, okay, if I'm not going to bring anything from this house, I'm bringing the recipe. And that was amazing. And actually I just told the soldiers to make it because I was like cooking in the kitchen and they were fired roasting the eggplants and they just chopped everything for me. It was just lovely. And they loved, loved, loved that recipe.

RICK BAYLESS: So you said you could use it as a condiment if you were going to spread it on something, what would you spread it on?

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: A piece of rye bread.

RICK BAYLESS: Of rye bread. I somehow guess that that's what you were going to say. It sounds just, Well, I'm going to do the same thing. Okay? When I when I make it, I'm going to do the same thing. So there is this thing in Mexican culture, culinary culture, and in fact, it sort of exists in lots of places that in the Spanish speaking world that they call Ensalada Rusa, Russian salad. And I do believe it's in this book and it's a whole bunch of vegetables with a creamy dressing. Right. So how do you make it in? How do you make a real one? Because in Mexico, honest to goodness, it's it is so popular to put out on buffets and stuff. You find it everywhere. And even though they call it Russian salad, it it doesn't really taste very Russian there because they just put a whole lot of pickle l'opinion with mayonnaise and then put that on boiled vegetables. And so that's your Ensalada Rusa and people just adore it. It's like potato salad in a way. But tell tell us about how it's made in Ukraine.

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: So these recipes are very controversial. And I just I just need to say that this book was.

RICK BAYLESS: Should I have called it Ukrainian Salad instead of Russian Salad?

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: Not it's not Ukrainian. So it has a long history, very twisted history. So when I was writing this book, it was all before war. It went to print before war. If I had my way and I foreseen the future, I would just remove it. First of all, because it's a Soviet dish, it's like this version I have in my book is from a Georgian chef, because in Georgia they make it lighter, they make it vegetarian, and they make it with fresh herbs, which I loved. So in my head it's a Georgian salad, Georgian potato salad. But their true story about this one is it was created in Russia. It was created by a French chef. Definitely not Russian flavors at all. But it was so lavish, it had like langoustines and it had the caviar and everything, all the expensive stuff. But then when USSR came, they like, okay, people are miserable. We want to keep it that way, but we want to give them something. We want to give them hope. And they brought back this salad. And with every year of USSR, the salad gets more and more cheap and miserable. And and this is what we get. But still, when you put potato and meat together with a creamy dressing this good.

RICK BAYLESS: What kind of meat?

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: So you can put a chicken breast. But what I grew up eating and everybody in Ukraine, Russia, etc. grew up eating is some sort of bologna chopped wood into the salad. So it was very traditional to serve it, do it during the New Years Eve, not anymore. I think in Ukraine everybody hates the salad. But what's what's saved me is this salad is more Georgian and I was smart enough to use a Georgian recipe, a Georgian interpretation. And I like it more because it's more vibrant, it's lighter. I did not use the heavy dressing and it has herbs, which makes it a little bit more healthier if it's possible.

RICK BAYLESS: Where what part of Ukraine is the Georgian influence the strongest?

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: Everywhere.

RICK BAYLESS: Everywhere.

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: The thing is, we embrace Georgian cuisine. I would say maybe ten or 15 years ago. We always had Georgian dishes because we were part of the USSR. And if you will go to Tbilisi, any city in Georgia, you will find Borsch everywhere. And same in Ukraine. You just travel to pretty much any city and you will find a Georgian cafe or restaurant.

RICK BAYLESS: How do you describe that cuisine, sort of in contrast to, say, Russian cuisine?

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: The flavors are somehow familiar and they use a lot of herbs that Russian and Ukrainian cuisine don't use. Cilantro and basil, especially purple basil. Just wonderful. And right now, cilantro is just slowly entering Ukrainian cuisine, just slowly because I did not grow up eating cilantro. And when I came back, I.

RICK BAYLESS: Noticed you have it in a lot of recipes.

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: And because of Georgia and I came here and I embraced cilantro, I started to like it a lot. And now I came back to Ukraine and I see cilantro on the menu. But it's not it's not something that most people will will prefer. They will say dill or parsley. That's the main herbs. Cilantro is just.

RICK BAYLESS: I noticed it at one of the dishes I've chosen to make for my dinner on Monday night. Has the of the parsley, the dill. And you put cilantro in there with those three. And I can't wait to taste that combination because that's not something that I have ever had before. What are the most famous Georgian dishes? So if we went into a restaurant and we go, Oh, that's a famous Georgian dish, what would they be?

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: Of course, khachapuri, khachapuri is a flatbread with a lot of cheese, and it can be made in many shapes and forms. And sometimes I think the most famous one is the one that's shaped like a boat with an egg and butter. And I have the recipe in the book, and this is one of my favorite recipes to teach people to make because it's simple. But everybody is like, Wow, what is that? This is incredible. And everybody's so proud when they make it. And it's just it looks incredible. And this is the most instagrammable recipe ever. So -

RICK BAYLESS: That was the first page I turned down in the book. Yeah.

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: And again, why this recipe is in the book? Because in Ukraine you can go and you can find this recipe because Georgia and Ukraine, I think we have a very similar spirit. And despite our government is not always on the same page, but people are supporting us. And I have a lot of Georgian friends. I traveled to Georgia to research for this book because I felt like I want to represent some of the recipes. And it was just lovely how they embraced. They refused to speak Russian with me and I was like, You are my brother. We spoke English and I know that the country is suffering from Russian aggression. Not the same way like Ukraine, but longer even. So I feel like we shared the same spirit and I'm proud that I have these recipes in my book.

RICK BAYLESS: Well, the reason that I was drawn to that recipe right away is because I really love Turkish food. And they make something called pide in Turkey that is that same shape. And so when I saw it in your book, I thought, Oh, that was the first tip off I had, that there was a relationship between the cuisines of all around that sea. And and then I looked at the way that you did it with a layer of the cheese and then covering it with the pastry and then more cheese on the top. And I was like, Yeah, I could go for that. I think I could go for that. And you put the egg on the top of it and.

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: Yes, and then when everything is like melted, you just mix everything together and just like take part of the bread and just dip and enjoy. This is this is incredible.

RICK BAYLESS: Now I'm really hungry.

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: Oh, my God.

RICK BAYLESS: No, that's a good one. Okay, so we need to talk a little bit. We've covered the basics of the book, except that you do have to talk about your the duck dish that's in there.

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: Okay. So everybody's asking, what's the favorite dish? And I oh, the answer is always the same. My grandmother's roasted duck. It is so good. It is very easy to make. And this is what I make on Thanksgiving. I don't make turkey. I make this duck. And this is the easiest duck ever. So you basically, you roasted whole. You need this Dutch oven that will hold the duck. I have this huge old one that is wonderful. And it is always with apples, because that's how my grandma made that. And I think apples create this lovely balance and you can serve duck with that apples, you can make a sauce out of that or you can serve the slices and the dog is so juicy, it is so beautiful, and it just the most easy way to cook it except for khachapuri. This is the second most impressive dish that you will just carve at the table and people will say, Wow, this is incredible and you don't spend any time making it, but you just rub it, put it in the oven, roasted and it just done.

RICK BAYLESS: Beautiful. Ok. You address this in your book, but talk to us about what happened to Ukrainian food during that that period from. I'm going to say it's like '41 or to '91, something like that. When Ukraine was part of the USSR.

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: Actually thinking it started earlier because we were part of the Russian Empire. And then once the Soviet Union formed. It was like somewhere around that they decided that this is a huge territory. How do we unite everything? We need one cuisine for everybody. So we now Georgian cuisine will give a few recipes, Ukrainian cuisine will give a few recipes, Russian cuisine will give a lot of recipes and a little bit of mish mash of French dishes. I don't know. I know why because they were admiring the cuisine so much they could not represent it properly, but still. And then they thought, if we will erase the culture, the culinary culture of every country and make something the same for everybody, then the country will be the same and we will unite everybody. And in Ukraine, we were forbidden to publish Ukrainian cookbooks, no research. A lot of recipes were lost. A lot of culinary culture is so, so deep that we need to dig it out. And that's why right now, a lot of chefs and a lot of culinary researchers, myself included, we are trying to understand what was Ukrainian cuisine before Russia, before USSR. And it's it's very hard because we have basically nothing that can lead us. We have a little bit and we have our imagination. And I think we just need to find the base for it and then dig and create something unique. And this is the proper time to do it, to just create flavors based on those almost lost knowledge.

RICK BAYLESS: That's really, really fascinating to me because if I'm not mistaken, they also outlawed teaching school in Ukrainian, right?

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: Oh, absolutely.

RICK BAYLESS: Everything was in Russian. And that's certainly one way that a culture will obliterate another culture. And same sort of thing has happened, I would say, with the Native American community that they are because their languages were so obliterated during many generations. With that, you often lose the cuisine and then the availability of ingredients to make Native American dishes was pretty much obliterated as well, except for a few foragers. And now that community is trying to do exactly the same thing that you guys are doing in Ukraine, which is to go back, talk to the elders, figure out if they have memories of certain dishes and how they would go together and sort of give them new life. But in that giving of new life, you're also going to give them new life in with a let's just call it a modern look, because we eat slightly different than we used to eat. And a good example is the cilantro in this book that yeah, we're used to using that. And yes, it's used in Georgian cooking. And so now it makes sense that it's going to be in a modern Ukrainian cookbook.

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: Absolutely. I so again, because of the USSR. It was very strict what you can grow and what you can't grow. So we have this all amazing land and we cannot grow golden bits. We could not grow a lot of things that would make sense to grow. We had asparagus before it was cool and then we lost it because of the USSR, because nobody understood it. It like, why do you grow it? Right. Go grow wheat or something like that. So when the whole world was developing their cuisine, Ukraine was standing still. And right now this is the time for us to create something, to collaborate, to learn modern techniques. And I see nothing wrong with embracing techniques from other countries. I want to see Ukrainian umami other than fermented stuff like pickles and dried mushrooms. I want Ukrainian misos, I want, which I had this creative project and I love it. I want to see more of that, more interesting concepts, more restaurants, more chefs. And I think we will see it in the next ten years. I already saw it in Ukraine, and I'm excited to share it with the world.

RICK BAYLESS: Okay, So now we have to talk about the state of Ukraine today. And I guess my my question is, you've just returned from Ukraine. So give us the lay of the land where what's what's it like in Ukraine right now and what's this? I'm really interested in the state of this emerging cuisine or the preservation of this cuisine.

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: So. Weirdly enough, people are more creative than ever. I feel like war created the background for people to just, okay, I'm just going to do what I want to do because there might be not no chance for tomorrow. So I'm doing it right now. I visited a lot of restaurants. I cooked with a lot of chefs, and what I saw is incredible creativity. So right now, Ukrainians are so traumatized and damaged by this war, and we don't want anything Russian. We just want our own. We want our peace. We want our cuisine. So basically, if you refuse to eat Russian dishes and you refuse to eat Soviet dishes, what do you eat? And people want to eat something then that belongs to Ukraine. And they are digging deep. They're searching for ingredients that are native to Ukraine. They are searching for methods. They're searching for old recipes. And basically, it's not it's not even recipes. It's just guidance. And with that guidance, they can create something unique and interesting.

RICK BAYLESS: If we want to support Ukraine in any way, what would you recommend? I mean, besides us cooking from your book and going to.

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: Anelya.

RICK BAYLESS: Anelya. Okay. How can we support?

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: So I traveled through the whole Ukraine, and I've been at the frontline and people who took me to the frontline, they are from International Aid Legion. So this is organization of volunteers, and they are so incredible. They are foodies as well. And they. They just I. I arranged everything during my trip. Everything was perfect. But this one, tiny details, that was the most important to me to go at the frontline and cook for our soldiers. And I had no arrangements because I didn't know anybody. And those people, they arranged everything in 30 minutes because they help those soldiers so much that the soldiers just welcomed me with open arms. They helped me. They built whatever needed to be peeled. They wash the dishes, they did everything because those people are helping them. And I used to think that. I can help multiple organizations, but now I feel like I need to focus my energy. Our military guys need all the support because they are the ones that protect us and that they allow people to have some sort of normal life. If you can say that. And International Aid Legion, they are just they are my personal friends. I support them. And they they evacuated 24,000 people from the occupied territories and the territories that were freed from Russian occupation. And they are just my superheroes, superhumans, and this is the organization I support.

RICK BAYLESS: Thank you very much for sharing that. I really appreciate it. Well, Anna, thank you so very much for spending the time with me. And thank you for opening my eyes to such a remarkable cuisine.

ANNA VOLOSHYNA: Thank you so much chef. Thank you.

[Audience applause]

[Theme music plays]

ALISA ROSENTHAL: That was Anna Voloshyna with Rick Bayless at the Newberry Library at the Chicago Humanities Fall Festival in October 2023. Head to chicagohumanities.org for links to both of their cookbooks as well as José Andrés and Mark Bittman, plus resources to get more information on all of the organizations mentioned or to send donations their way.

Chicago Humanities Tapes is produced and hosted by me, Alisa Rosenthal, with help from the awesome staff over at Chicago Humanities. Shout out to the hardworking staff who are programming these live events to bring them to you and the production staff who’s making them sound super crisp. For more than 30 years, Chicago Humanities has created experiences through culture, creativity, and connection. Check out chicagohumanities.org for more information on becoming a member so you’ll be the first to know about upcoming events and other insider perks. The podcast will be taking a winter break, but we’ll be back soon with lots of new episodes for you. You can always listen through our backlog of episodes of Chicago Humanities Tapes, available wherever you stream your podcasts. And if you’re so moved, spread the holiday cheer and leave a rating and review, share your favorite episode, and hit subscribe to be notified when we’re back. Wishing everyone a safe and happy winter. And in the meantime, stay human.

[Theme music plays]

[Cassette player clicks closed]

SHOW NOTES

CW: Light profanity

José Andrés ( L ) and Mark Bittman ( R ) at the First United Methodist Church at the Chicago Temple at the Chicago Humanities Fall Festival in October 2023.

José Andrés, The World Central Kitchen Cookbook

Mark Bittman, The Best American Food Writing 2023

![[A young woman with long straight blonde hair and blunt bangs wearing a casual olive suit sits in an ornate wooden chair with her legs crossed, smiling and gesturing about something big. A smiling man sits in a similar chair across from her, with nice tousled hair and a blue crewneck sweater.]](https://assets.chicagohumanities.org/uploads/images/Voloshyna_Bayless_Live.width-800.jpg)

Anna Voloshyna ( L ) and Rick Bayless ( R ) at the Newberry Library at the Chicago Humanities Fall Festival in October 2023.

Anna Voloshyna, BUDMO! Recipes from a Ukrainian Kitchen

Rick Bayless cookbooks

annavoloshyna.com (sign up for her mailing list for her foolproof khachapuri recipe)

Aneyla Restaurant, Chicago

Humanitarian aid to Ukraine:

Recommended Listening

- Podcast

- May 30, 2023

Top Chef's Kwame Onwuachi on Authentic Cooking

- Podcast

- July 11, 2023

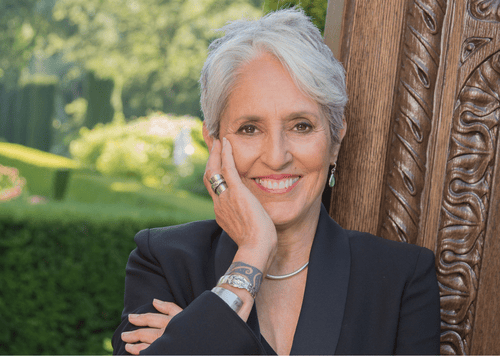

Joan Baez on Music, Art, and Lifelong Activism

- Podcast

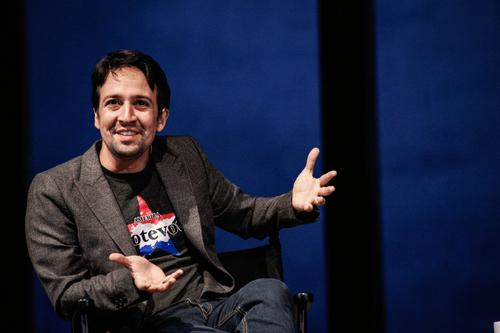

- March 19, 2024

Lin-Manuel Miranda Shares the Secrets to Making Great Art

Become a Member

Being a member of the Chicago Humanities Festival is especially meaningful during this unprecedented and challenging time. Your support keeps CHF alive as we adapt to our new digital format, and ensures our programming is free, accessible, and open to anyone online.

Make a Donation

Member and donor support drives 100% of our free digital programming. These inspiring and vital conversations are possible because of people like you. Thank you!