The Sweetly Sly Art of Alberto Aguilar / El gentilmente travieso arte de Alberto Aguilar

Exclusive Interview / Entrevista Exclusiva

S3E17: Alberto Aguilar

Apple Podcasts • Spotify • Overcast • Pocket Casts

Chicago-based artist and educator Alberto Aguilar is known for his powerful and off-the-wall juxtapositions, from coiling water hoses in gardens to arranging donated shoes in front of the Centro Romero immigration aid center, or sneakily propping open a side door of the Art Institute, inviting other troublemakers inside…

Aguilar joins podcast host Alisa Rosenthal for an exclusive interview at his home studio, where they chat about his art-making process as well as preview Chicago Humanities’s free day of events, Pilsen Day Art & Experiences on Sunday September 29, 2024.

El artista y docente radicado en Chicago Alberto Aguilar es conocido por sus poderosas y extravagantes yuxtaposiciones, desde enrollar mangueras de agua en jardines hasta arreglar zapatos donados frente al sitio de ayuda a inmigrantes Centro Romero, o abrir sigilosamente una puerta lateral del Instituto de Arte invitando a otros alborotadores a entrar.

Aguilar se reune con la presentadora de podcast Alisa Rosenthal para una entrevista exclusiva en el estudio de su casa donde conversan sobre el proceso de creación de su arte, así como un adelanto del día de eventos gratuito Pilsen Day Art & Experiences (Día de Arte y Experiencias en Pilsen) del Chicago Humanities, el domingo 29 de septiembre de 2024.

Read the Transcript

ALBERTO AGUILAR: I started going to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago after the semester was over to collect the paintings that were left behind, you know to reuse the canvases. And a focus emerged. The self-portraits. I started to hang them on the stairwell in my house. Even though I don't know these students, I feel a connection to them.

[Cassette player clicks open]

[Theme music plays]

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Hey all what’s going on, you’re listening to Chicago Humanities Tapes - the audio extension of the live Chicago Humanities Spring and Fall Festivals. I’m Alisa Rosenthal, and today, I’m bringing you my conversation with Chicago-based artist and educator Alberto Aguilar, Chicago Humanities’s inaugural Artist-in-Residence, made possible by a generous grant from the Terra Foundation for American Art’s “Art Design Chicago” initiative.

Art Design Chicago is a special series of events and exhibitions now through 2025. They partner with local organizations to really showcase those creative communities - from museums to your El stop to that neighborhood you’ve always wanted to check out. For more information on Art Design Chicago, head to artdesignchicago.org or check our show notes.

Chicago Humanities is partnering with neighborhoods all across the city in our just announced Fall 2024 season! We’ll be collaborating with Pilsen, UIC, Northwestern, Lakeview, and Hyde Park. Join us for amazing conversations with Joan Baez, Malcolm Gladwell, Connie Chung, Erik Larson, R.L. Stine, Jamaica Kincaid, Patti Smith, Randy Rainbow, Tegan and Sara, and so much more. Tickets are on sale to members September 10th and then available to the general public September 12th. All membership and ticket information is available at chicagohumanities.org.

[Music plays]

Today’s guest, Alberto Aguilar, is a Mexican-American artist known for his powerful and off-the-wall juxtapositions, creating art where you don’t expect it. He’s coiled water hoses in gardens to look like a “sign” to those looking for one. He’s arranged dozens of donated shoes in front of Centro Romero, Chicago’s refugee and immigration aid center. He’s sneakily propped open a side door of the Art Institute, inviting other troublemakers inside…

An educator at the School of the Art Institute, as well as a father of four, he draws on the unbridled creativity of young people across a variety of mediums - photography, installation, performance art, painting.

He invited me to his home studio to chat about his art-making process as well as preview Chicago Humanities’s free day of events, Pilsen Day Art & Experiences happening on Sunday September 29, 2024.

Pilsen Day Art & Experiences was curated by Alberto, so you can expect everything from live music to a deep dive into the Chicano Arts Movement to an impressive 50 ingredient molé.

Born in Cicero, Aguilar is a 2024 US Latinx Artist Fellow and a recipient of the 3Arts award. He has shown at various museums, galleries, storefronts, and street corners around the world including the Museum of Contemporary Art and the National Museum of Mexican Art in Chicago, the Queens Museum in New York, El Cosmico Trailer Park in Marfa, Texas, El Lobi in San Juan, Puerto Rico, and the I-80 rest stop in Iowa.

This is Alberto Aguilar and myself, chatting in his home studio, with the windows open on a beautiful summer day.

[Theme music plays]

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Well, let's see, I am recording. I'm not sure how our levels are, but let's see. Check one, check two. Would you mind giving me a check?

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Yes. I don't mind giving you a check. Check one check two.

[Theme music plays]

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Alberto. Hello.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Hi, hello.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Where are we?

ALBERTO AGUILAR: We are in my house in Forest Park, Illinois. At the dining room table in the main space.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: And what can you tell me about this table?

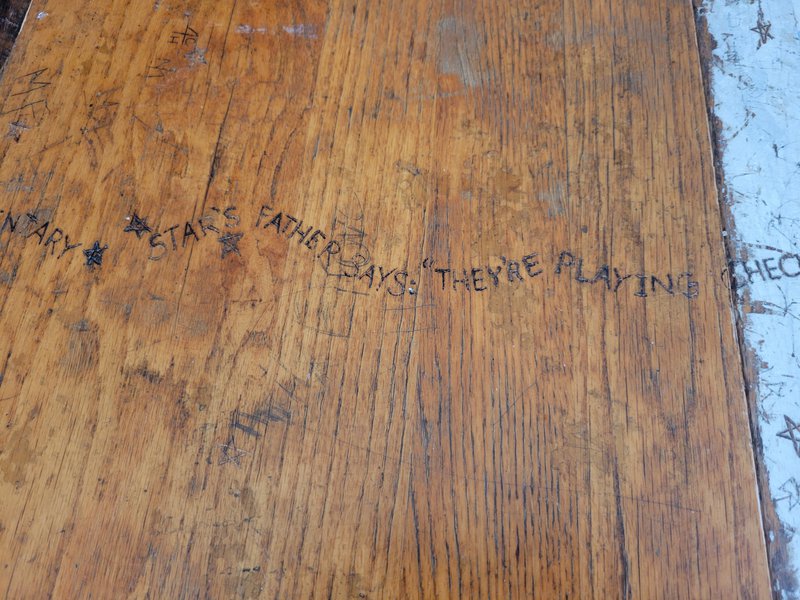

ALBERTO AGUILAR: This table was, is on I guess it's on loan, technically, from Bryan Saner and Teresa Pankratz. It's a table that's made out of writing tables, from Chicago Public Schools that were closed down in 2013, 14. And, it's like, you know, it's made out of different tables. At the bottom, you can see there's some legs from some of the tables that almost look like cow udders. And there's also like an inscribed story on the surface of the table that's meant to be read by guests to a dinner party.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: I immediately noticed the story in the stars. And, it's funny that we've set up this massive technological audio setup on this table. What kind of things typically happen around this table?

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Well, I'm glad you know that it could function as, as a sound studio, a sound equipment holder. I mean, typically what happens here is a little bit of everything happens here. People work on their computers. Drawings are made. Ping pong is played. But the main thing that happens is, is dinner. Maybe not in the summertime as much because we eat on the porch.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Yeah.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: But dinner's had here. Dinner with my family, but also dinner parties.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Yeah.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: One of the things I liked about the table was, is that it's so big, you could probably fit 12 people on this table.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: When I think of a dinner table, this is what I think of.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: That's good.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: This has so much more.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Doesn't look too messy?

ALISA ROSENTHAL: No, it's the perfect amount of messy.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: I say messy because it kind of is like a collage, also of different parts.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Yeah, I see multiple tables here, and I think this table is a really interesting place to start because we've just, concluded part of a house tour that you've given me. And I was really struck by, I know you work with domesticity a lot in your work, and being in your home and seeing how your family makes creative work just kind of as they breathe or as they do things. How does the domesticity of day to day life and the domesticity that you're putting into art work, how do those play together?

ALBERTO AGUILAR: I mean, I would say that that component of the work used to be stronger. It used to be a more, prominent part of the work, and I think it still is, but not as much because, the kids are now older, so. And some of them have gone away. But, I think that for me, it was a way, you know, I think when it, when I, when I was a, when I studied painting at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, I remember there was a teacher, a professor there who one time said, you can't have kids and be an artist. Just you just can't do it. And when I heard that, I was kind of confused. And I also, deep down inside, I think that I wanted to prove that idea wrong.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Yeah.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: So I ended up having four kids, and I probably would have had more if Sonia didn't put a stop to it. But, I think it was a slow realization, but I but I came to realize that in order to be a father who's present and an artist who is able to produce work I had to sort of combine those two things. So that's what I did.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Yeah.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Combine them. And, I made work in the midst of living.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Yeah.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: And then sometimes in collaboration with the kids.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Yeah. I feel like I know, a lot of people who would have pursued art more, but felt like the desire to have a family was at odds with that. So what have been the successes, really, of having a big family, making art, having that kind of more fluid, nontraditional lifestyle?

ALBERTO AGUILAR: The successes are the that that it's a very generative, you know like.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Yeah.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: You think like I mean just going back to what this professor said, right? Like he's saying the opposite. He's proposing this idea that that that it's not generative, that, that you won't generate anything right?

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Right, right.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: And and what I found is that it's extremely generative in many, many ways. Just that I mean, I was very prolific, you know, because I was always in the studio and an idea could come in at any at any given moment. And I can see through that idea, I didn't have to go to a separate studio space to make it. And then it's generative also in the sense that that it, it sort of affects the kids. Right. And some of the kids became artists or designers or at least creative thinkers. And, so I think that it's generative in those kinds of ways.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Yeah, I think too, something I was really struck by with your work and this house tour, too, is that there's so much we can learn from young people. And I think - I was an educator for years; I did music and drama - and there's a lot that's, really inspiring about children. I found it really interesting how your work really pulls from the creative ideas and excitement of your own children and also your students. Can you speak to what what is the quality or what are some of the qualities that we get from young people that perhaps other people aren't? When adults say, like they don't like kids. You know what what are they being deprived of really?

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Well, I'll start by talking about old people going back to these professors. You know, like when when I was in school, like there was this thing of, like, extremely discouraging your students, you know, like that was that was the approach when I was in art school. It was this idea of, like like putting your students through complete hardship and squashing them in order for them to like, you know, first of all, like, testing whether they're able to be artists. Right. I think that was one of the functions of treating the students so harshly and critically. But also, yeah, the idea of like, having them dig a little deeper. But I felt that a lot of people were squashed. You know, a lot of people, didn't pursue art because it was so the, the the criticism was so harsh. But what I find is that yeah, young people have so much, there's so much promise. There's so much, so much excitement. There's so much clarity that I like to tap into. I love being around that. I don't like being around old people who are, you know, like, what's the word when they're jaded when, yeah, they're negative. When they're critical. I don't like that energy. You know, I try to stay as far away from that as possible. I like being around, young people who have, great ideas and great energy, and I like supporting that. But but I also like tapping into that, you know, and, like, bouncing off of that and, and, so, yeah, I regularly collaborate with people that are younger with younger than I am. But yeah, I mean, I think of it as a teaching moment, but I also think of it as a great learning moment. And I think of the classroom that way. Like, it's not only about what I could give the students, it's about what I can get from that experience as well, and that's what makes it more exciting. I think sometimes teachers become jaded, right? Because -

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Yeah.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: They're just teaching the same old thing and that's boring. But what happens when new generations of artisan students come in is that it's just new information and new possibilities.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Yeah being able to tap into that. That's the thing I feel like as adult artists, we're all trying to get back to is that kind of unbridled creativity. On the house tour you spoke to some self-portraits that you've collected over the years. Can you speak to those?

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Yeah, I, I, I would go, I started this, I don't know what when it started, it was probably like right after the pandemic stay at home order. I started going to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago after the semester was over to the painting department to collect paintings, to collect the paintings that were left behind, you know, to to use, to reuse the canvases or to collect paintings that I liked that I could possibly hang in my house. And like, with everything, through time, a focus emerged. And I would say the focus was the self-portraits, because I, I painted a lot of self-portraits when I was a young student. And to me, there's something very like, something very, potent in them, you know, like, just that you have this sort of raw expression of the students, you kind of have their presence, you kind of have their spirit in the in the painting. And so the students would leave these because sometimes a lot of times at the end of the semester, because the students are aren't from here, they're from Chicago, they're flying out to wherever. They'll just leave paintings. And, yeah, my focus ended up becoming the self-portraits because of, because I was drawn to them. And because I've been teaching so long and and and I hang them, I started to hang them on the stairwell in my house to go upstairs. Just because I also felt that that was that it was a it's a transient space, right. And I just felt like it was a good space to be able to have this contact or have this connection with these students for me, like I teach all the time. So, it's a way to, to represent my teaching, even though I don't know these students, I feel a connection to them.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Yeah. Is, self-portrait typically an early assignment as you're beginning art school?

ALBERTO AGUILAR: It tends to be, it still seems like it's a it's an assignment that's given in, in the first year of teaching painting. But I think students are just drawn to do it naturally. But. Yeah. And, and these probably came out of assignments to do a self-portrait. And one of the things that I do when I see these self-portraits is I try not to judge them, whether it's good or bad. I just collect them. And, I think you I might think one is bad, but when it's on the wall with all the other ones, it it communicates in a different way.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Yeah. What advice would you give to someone who was always drawn to art, visual art, performance art, didn't really know where to start?

ALBERTO AGUILAR: I think, start anywhere. And just be persistent with that thing. I think you could really start anywhere. Like there's something arbitrary about making, that I think is amazing. Just that, I mean, painting is easy. I don't I don't really paint that much anymore. But, you know, like, if I was to start working on a canvas, right, like I could make any mark. I could do anything. It could be a really bad mark. And of course, what, what tends to happen is that you have self-doubt towards that mark, but it's the accumulation of marks and the persistence and the belief that something's going to turn out helps you see that thing through. And you don't know what it is, right? And I'm using painting, but I think it could be related to anything. To anything like taking photos on my phone. Like some, like I you could look at my photo photo roll. Like if I shoot a photo, sometimes I'll shoot it like 30 to 50 times because I shoot one thing at the beginning and I think I have it, but it's not until I shoot it like 30 times that, that I start to hone in on the picture plane, the light. Something happens in the light. I realize something that is the most interesting thing about that image. So I think that has to do with persistence and belief that something is there, but you just have to you do have to dig a little deeper.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Yeah, I think that that confidence, that's the hard part. The judgment of the mark is the easy part. And then the confidence to move forward I think is the hard part.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: It is, but it's also not, if you think - I mean, it is a hard thing, but it's just it really just is a state of mind if you think about it and you get good at it. That's the other thing. You get good at believing in what you're doing.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Yeah.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: But you have to put it into practice.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Yeah.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: And I don't it's funny because I and I know that it exists for some people, but for me personally, I don't believe in artistic block at all. Because I, I do this thing. I think I've set up something in my practice that I'm using the word generative again.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Yeah.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: That is generative that ideas can never stop flowing. Because first of all, I've gotten good at this belief, right? And second of all, I have this sort of persistence. And, I yeah, I set up sort of like a generative system so that something always turns out, no matter what I do, something will always turn out.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: This is totally in line with, everything I know about how how people have tried to document and understand creativity is it's a, it's kind of the same thing with, motivation. Right? If you're sitting and not doing anything, you're not going to feel motivated. Once you start being active.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Yeah.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: You'll magically feel motivated. You reminded me of a quote, I can't remember it verbatim, from Jim Henson of The Muppets. There was a big exhibit on him that came through, I think was the Museum of Science and Industry a bunch of years ago. There was a quote on the wall that said, there's there's always ideas flying around. You just have to be open to catch them. And it sounds like you've figured out how you work and have made that system so that even being in your home and seeing how creative output, right? Seeing how tangible things that you've made that you can share just kind of flow. But that that comes from somewhere so that you don't have to stress over an artistic block.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Yeah.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Asking for a friend you know.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: And I, no no no no, I like the word open.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Yeah.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: It's a simple word.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Yeah.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: You know, remaining open. You know, like, I think that's that's what I'm talking about when, like, artists, people become jaded, right? It's that they they close themselves off. And, you know, it could get really scary too, because you could really get good at closing yourself off. Right? And I, I personally never want that to happen to me. You know, like, I don't want to close myself off so much that, there's nobody around me. One of the reasons and I have nothing against painting because I still paint occasionally. But I think that's for me that's one of the reasons why I decided I didn't want to be a painter, because there was this sort of like loneliness in that way of working that I didn't want to go further with. You know, like, I didn't want to just be in the studio working on these paintings. I know that something amazing would come out of it. But at the sacrifice of something.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Yeah. I mean, it's kind of that universal desire to even in like, work life. What kind of work do I like doing? How is this sustainable? How is this going to bring me joy as much as I can, looking at that within artistic life as well. I guess I'd never thought about, those kind of nuances between, well, I can do this, I'm talented at this. I can put time into it, but it's not going to give me what I want day to day. And, a lot of what I'm hearing is like active decisions to pursue the things that are bringing you joy, pursue the things that, you're naturally curious about and really growing that. And in doing that, that's what's keeping this openness. I mean, it ties back to working with students and working with young people just the way that they think, right? Is that like, well, that's interesting. I'm not scared of that. Okay. Boo boo boo.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Yeah.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: I noticed something that I wanted to ask you about. I feel like, humor pops up a lot in kind of a subtle way in your work and even in our tour, there's a lot of really interesting layers and juxtapositions. There's, I believe, a classical music playing from your bathroom right now and, I'm interested in: do you think about humor? Does it just kind of happen? What are your thoughts?

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Yeah, I. I think it hap it just happens, naturally. I do think humor is important. And it's and you know, like maybe, maybe also referring to it as play. But like I. I think that for me, play and humor are important to the artistic process because they, again, just make it more enjoyable.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Yeah.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: That's one thing. But I think that that life is, is, there's also funny things that happen in life.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Yeah.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: And, I observe those things, and, sometimes I observe them, you know, accidentally, or just through, like, they just the coincidences happen, that are, that are humorous or, but I think in terms of play. Like there's something about play that is like, I was talking about the photo where I, put the the, drying rack over that sort of fig tree when I was in Spain, in an apartment like there, I don't know what that means when you put those two things together, but that sort of funny act of putting something where it doesn't belong, it creates a new meaning. And I think it's that it's through that new meaning or that humor that you connect with the viewer, you know, if it's not, if there's not, like some sort of humor or act of play. Yeah. You could connect with the viewer, but but I, I like for the viewer to have some sort of revelation or encounter when seeing my work. The same encounter that I have when seeing those two objects that don't belong. Like, I like to share that moment with the viewer. And then that that moment sort of conjures something in the viewer. And whatever makes them laugh, makes them joyful.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: I noticed with that, that photo you showed us of the the drying rack with the tree through it. My first thought started going into kind of the story of it and like, who is this character who dries their clothes around a tree? How did the tree get there? I'm thinking about the tree. And then I'm like, oh, right, this is a photo. You know, it, it kind of instantly got me thinking. That's that's such a a fun way to connect with someone.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Well, that's connected to this word open that you use earlier. I, I was writing something the other day about. I'm trying to remember. It was this idea of, like, keeping things open for the viewer. If I was to make up a painting that was very expressive and I just put, a certain feeling into it, you know, like I or I told a very specific kind of narrative like, it has the potential to close the read down a little bit. Like if I just put my own emotions into it, right into, into an artwork, like then it's about that emotion, where I find that if I just observe and I like be factual even. It's funny because factual is like the opposite of humor. Like sometimes when I make factual moves or I just observe, and I don't bring my own emotions into it. And then I put something forth to the viewer, like, I feel like there's more of an openness to it where the viewer can bring their own thoughts to it, versus me telling somebody what to think.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Yeah, that makes total sense. And this is kind of a perfect segue into the curation that you're doing for Chicago Humanities in just, a handful of weeks, a whole day of of art and experiences. And would you mind talking through a bit of a preview of what -

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Yeah.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: What that looks like.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Not at all. Well, first of all, it's an entire day, which I was kind of like, I was a little confused. It was like, all of this is going to happen on one day. But as I went on, it made sense and it made perfect sense within my practice, you know, to to create like an experience that's an all day experience. And I'm guessing that not everybody's going to stay for the whole thing, but I'll be there. And, I'm really excited and about the things that came together for this program for this day, and just how they came together was, was, was, was a very interesting creative process. The program, starts with Museum Church, at the National Museum of Mexican Art in the auditorium. We're going to, it's it's a Sunday. So I thought it was fitting to have, like, a church, something that feels kind of like a church service. So my good friend Jorge Lucero is going to, give a sermon. He's a he's actually a pastor's son, but his sermon is going to be an etymological sermon. So he's going to he's going to come in with his etymology dictionary instead of the Bible. And he's going to like dissect one word during the sermon. Jesse Malmed is going to he, he's, certified like he could marry people. What do you call that?

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Ordained. I am also ordained. I think I'm technically, like, Ordained Rabbi Rosenthal. I'm not a rabbi, but I am ordained.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Yeah, exactly. He's. He's also ordained. But he in the past married form and content. I don't know what he's going to marry this time, but he he marries, he could very well marry ideas or marry inanimate, inanimate objects. And then there's, two sound artists that are going to, perform, you know, what's equivalent to the worship section of, of a church? And, so that's the first program then. Right? And then there's going to be like food, you know, like, like donuts and coffee afterwards. Like there is at church sometimes. And then it's going to go right into Harry Gamboa Jr.'s, lecture. Harry Gamboa Jr., if you don't know, is, member of ASCO group from the 1970s, Chicano artist who did some really amazing, radical work that I didn't know anything about. For some reason, I was never exposed to this in art history classes. It was actually my daughter one time sent me an essay and she said, you need to read this essay. And it was summertime. And I was like, in my head, I was like, I'm not going to read an essay in the summer. But she kept bothering me about it. And I eventually sat in the hammock and I read this essay, and I was blown away by this work. So, she studies at Occidental College in Los Angeles, and this is sort of her focus. Like she really focused in on ASCO's work. So I, invited the founding member Harry Gamboa Jr. to give a lecture, and then we're walking over to, the gallery, PACH or "pack" Gallery. And I invited six artists to make response works to the early work of ASCO. And from what I understand, the founding, the members were actually still in high school when they started this, this movement, this group, which goes back to talking about young artists, they're very well known for this piece called Spray Paint LACMA. They were at the L.A. County Museum and, they could not this was in the 70s. They couldn't find any, like, representation of Chicano artists. So they would go to the curator and ask them, why is there no Chicano artist in the, in, in the museum? And the the curator said something like, you know, like Chicano artists are gangbangers and graffiti artists. So the next that that night, the group members spray painted all of their names on the on on the museum. And they have this historic photo of that moment. And, it was a what's most interesting is that the L.A. County Museum since has had a giant retrospective of their work and and hold many of their works in their collection. So that's that's happening. Six artists, Maria Gaspar, Josh Rios, Nancy Sánchez, among others, are going to are going to sort of make represent the new, new versions of these ASCO works or new interpretations of these works. And then the the day ends in the parking lot of the National Museum of Mexican Art, where I invited 18 artists to show their cars, cars with installations.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Cool.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Cars with stages that are have programing in the back, cars that are covered with a giant bandana. There's going to be a variety of things and it's called Auto Portrait Spectacular. It's a play on words, like self-portrait, auto portrait. And then, the night truly ends with, three musicians that are going to play on the stage in the parking lot.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Very fun.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: And it's, it's it's moving a little more towards, like, screamo music or heavy metal music.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: I mean, metal was just featured in the Olympics opening ceremony.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: I didn't see that.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Yeah. Gojira, along the Seine.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Wow.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: It was metal, so I think it's having a moment. Yeah. The amount of, juxtapositions and, it just. It sounds like a really special day. I know people will come out and have a good time.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Yeah, I'll be there all day long. And I believe that if somebody is there all day long, it will be an experience to remember.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Oh, yeah. I've done some of those neighborhood days. The whole day. It is. It is like a marathon that feels you sleep hard the next day. It's good. I have one last question for you. Since so much of the day, and especially since you'll be there the whole day, you will be meeting a lot of strangers, and I feel like this is something that I've encountered a lot in the stuff you're doing. And here we are. We've met once before, but otherwise strangers, you know, and, what are you looking forward to in this full day of programming that will really have you engaging with strangers?

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Well, that's a good question. I have to think about it. I, I'm excited to meet people and to hear their responses. It's funny because I didn't used to be into meeting strangers. Right. Like my I was one of those people that was really uncomfortable in a classroom with classroom discussions or at a table at a wedding where you're with strangers. But I've kind of gotten good at it because I've thrown myself in those situations. I used to do these dinner parties to with with un with strangers, back a few years back. And actually, one thing that I forgot to mention is the 50 ingredient molé that's also going to be served, which is my sort of like signature molé that is made up of 50 ingredients. This idea of like pushing the boundaries of how many ingredients you could put in a sauce, before it falls apart. That, and I always thought of that molé as a metaphor for bringing together strangers. You know that. Because I remember when I was going to when I was doing these dinners, I told my, my mother that I was going to make this 50 ingredient molé. And she was like, it's not going to work. There's that's too many ingredients. And then I was like, you know, in the end it has to taste like something. So I would say that that's what I look forward to. I just look forward to the to the collage of people that will be there, both as the artists showing the cars, right, but also as the people sort of experiencing these moments and, and, and how they, how they respond to it is going to be interesting also.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Well can't wait. Anything else you wanted to -

ALBERTO AGUILAR: I -

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Shout out?

ALBERTO AGUILAR: I could go on and on and on. Oh well, the last thing I want to shout out is. Yeah, go see the show at the Cleve Carney Museum at the College of DuPage. I give I like, I give tours to people. College of DuPage is slightly far from the city, but there's magic over there. And I'm very much into finding magic. And I found the magic in that place, and I actually take people through it. Not just my show, but also the preserve in the back of the college. Like there's just like a magic energy there that I like to take people to along with seeing my show, because it also enhances the show experience.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: That's perfect. That's all I got. Alberto, thank you so much.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Thank you. Thank you.

[Theme music plays]

ALISA ROSENTHAL: For more information on Alberto Aguilar and the day of events he’s curated for Chicago Humanities’s Pilsen Day Art & Experiences on September 29th, head to the show notes, or directly to chicagohumanities.org to register for the free events.

Chicago Humanities Tapes is produced, edited, and hosted by me, Alisa Rosenthal, with production, story editing, and copywriting assistance from the team at Chicago Humanities.

New episodes drop every other Tuesday wherever you get your podcasts. Make sure to click “follow” to be alerted when new episodes are available. If you like what you hear, give us a rating, leave a review, or share your favorite episode. We’ll be back in two weeks with a brand new episode for you. But in the meantime, stay human.

[Theme music plays]

[Cassette tape player clicks closed]

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Empecé a ir a la escuela del Instituto de Arte de Chicago después de que terminaba el semestre para recoger las pinturas que quedaban, ya sabes, para reutilizar los lienzos. Y surgió un enfoque. Los autorretratos. Empecé a colgarlos en las escaleras de mi casa. Aunque no conozco a estos estudiantes, siento una conexión con ellos.

[El reproductor de casets hace clic para abrir]

[Suena el tema musical]

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Hola a todos, están escuchando Chicago Humanities Tapes, la extensión de audio de los festivales de Primavera y Otoño de Chicago Humanities en vivo. Soy Alisa Rosenthal y hoy les traigo mi conversación con el artista y docente Alberto Aguilar, quien inaugura el programa Artista-en-Residencia de Chicago Humanities que es posible gracias a una generosa beca de Terra Foundation for American Art’s “Art Design Chicago” (“Diseña Chicago” iniciativa de la Fundación Terra para el Arte Americano).

Art Design Chicago es una serie especial de eventos y exposiciones desde ahora hasta el 2025. Se asocian con organizaciones locales para mostrar realmente esas comunidades creativas, desde museos hasta una estación del El y ese vecindario que siempre quiso visitar. Para obtener más información sobre Art Design Chicago, visite artdesignchicago.org o consulte las notas de este programa.

¡Chicago Humanities se está asociando con vecindarios de toda la ciudad en nuestra recién anunciada temporada de Otoño 2024! Colaboraremos con Pilsen, UIC, Northwestern, Lakeview y Hyde Park. Únase a nosotros para las increibles conversaciones que tendremos con Joan Baez, Malcolm Gladwell, Connie Chung, Erik Larson, R.L. Stine, Jamaica Kincaid, Patti Smith, Randy Rainbow, Tegan y Sara, y mucho más. Los boletos estarán a la venta el 10 de septiembre para nuestros miembros y disponibles para el público en general el 12 de septiembre. Toda la información sobre membresías y boletos está disponible en chicagohumanities.org.

[Suena música]

El invitado de hoy, Alberto Aguilar, es un artista mexicano-estadounidense conocido por sus poderosas y extravagantes yuxtaposiciones, creando arte donde no lo esperas. Ha enrollado mangueras de agua en los jardines para que parezcan una “señal” a quienes buscan una. Ha colocado docenas de zapatos donados frente al Centro Romero, una instancia de ayuda en Chicago para refugiados e inmigrantes. Ha abierto a escondidas una puerta lateral del Instituto de Arte, invitando a otros alborotadores a entrar...

Docente en la Escuela del Instituto de Arte, así como padre de cuatro hijos, aprovecha la creatividad desenfrenada de los jóvenes a través de una variedad de medios: fotografía, instalación, performance y pintura.

Me invitó al estudio de su casa para conversar sobre su proceso de creación artística y para ver un adelanto del día de eventos gratuito de Chicago Humanities. Pilsen Day Art & Experiences (Día de Pilsen Arte y Experiencias) que será el domingo 29 de septiembre de 2024.

Día de Pilsen Arte y experiencias fue curado por Alberto, por lo que puedes esperar de todo, desde música en vivo hasta una inmersión profunda en el movimiento artístico chicano y un impresionante mole de 50 ingredientes.

Nacido en Cicero, Aguilar es 2024 US Latinx Artist Fellow (Artista Becario Latino EE.UU. 2024) y recibió el premio 3Arts. Ha expuesto en varios museos, galerías, escaparates y esquina de calles alrededor del mundo, incluido el Museo de Arte Contemporáneo y el Museo Nacional de Arte Mexicano en Chicago, el Museo de Queens en Nueva York; El Cosmico Trailer Park en Marfa, Texas; El Lobi en San Juan, Puerto Rico y el paradero de la I-80 en Iowa.

Aquí estamos, Alberto Aguilar y yo, charlando en el estudio de su casa con las ventanas abiertas en un hermoso día de verano.

[Suena el tema musical]

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Bueno, veamos. Estoy grabando. No estoy segura de cómo están nuestros niveles, pero veamos. Checo uno, checo dos. ¿Te importaría darme un cheque?

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Sí. No me importa darte un cheque. Checando uno, checando dos.

[Suena el tema musical]

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Alberto. Hola.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Hola, hola

ALISA ROSENTHAL: ¿Dónde estamos?

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Estamos en mi casa en Forest Park, Illinois. En la mesa del comedor del espacio principal.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: ¿Y qué me puedes decir sobre esta mesa?

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Esta mesa estaba, está en préstamo, técnicamente, de Bryan Saner y Teresa Pankratz. Es una mesa hecha de escritorios de Escuelas Públicas de Chicago que cerraron en el 2013, 14. Y, ya sabes, es como si estuviera hecha de diferentes mesas. En la parte inferior se pueden ver unas patas de algunas de las mesas que casi parecen ubres de vaca. Y también hay una historia escrita en la superficie de la mesa que debe ser leída por los invitados a una cena.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Inmediatamente noté la historia en las estrellas. Y es curioso que hayamos instalado esta enorme configuración de audio tecnológico en esta mesa. ¿Qué tipo de cosas suelen pasar alrededor de esta mesa?

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Bueno, me alegra que sepas que podría funcionar como, como estudio de sonido, como soporte para equipos de sonido. Quiero decir, típicamente lo que sucede aquí es un poco de todo lo que sucede aquí. La gente trabaja en sus computadoras. Se hacen dibujos. Se juega al ping pong. Pero lo principal que sucede es la cena. Quizás no tanto en verano porque comemos en el porche.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Sí.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Pero son las cenas. Cenas con mi familia, pero también fiestas con meriendas.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Sí.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Una de las cosas que me gustó de la mesa fue que es tan grande que probablemente cabrían 12 personas en esta mesa.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Cuando pienso en una mesa para cenar, esto es en lo que pienso.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Eso es bueno.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Esto tiene mucho más.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: ¿No parece demasiado desordenado?

ALISA ROSENTHAL: No, es la cantidad perfecta de desorden.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Digo desordenado porque es como un collage, también de diferentes partes.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Sí, veo varias mesas aquí y creo que esta mesa es un lugar realmente interesante para comenzar porque acabamos de concluir parte de un recorrido que me diste por la casa. Y me sorprendió mucho, sé que trabajas mucho con la vida casera en tu trabajo, y estar en tu hogar y ver cómo tu familia hace un trabajo creativo simplemente mientras respiran o mientras hacen cosas. ¿Cómo funcionan la vida casera de la vida cotidiana y la que estás poniendo en el arte? ¿Cómo interactúan?

ALBERTO AGUILAR: O sea, yo diría que ese componente del trabajo solía ser más fuerte. Solía ser una parte más destacada del trabajo, y creo que todavía lo es, pero no tanto porque los niños ahora son mayores. Y algunos de ellos se han ido. Pero creo que para mí fue una manera, ya sabes, creo que cuando yo, cuando era, cuando estudiaba pintura en la Escuela del Instituto de Arte de Chicago, recuerdo que había un profesor, un profesor que una vez dijo: no se puede tener hijos y ser artista. Simplemente no puedes hacerlo. Y cuando escuché eso, me sentí un poco confundido. Y yo también, en el fondo, creo que quería demostrar que esa idea estaba equivocada.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Sí.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Entonces terminé teniendo cuatro hijos, y probablemente hubiera tenido más si Sonia no le hubiera puesto fin. Pero creo que fue un descubrimiento lento, pero me di cuenta de que para ser un padre presente y un artista capaz de producir trabajo, tenía que combinar esas dos cosas. Entonces eso es lo que hice.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Sí.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Combinarlos. E hice trabajo en medio de la vida.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Sí.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Y luego a veces en colaboración con los niños.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Sí. Siento que conozco a mucha gente que se hubiera dedicado más al arte, pero sintieron que el deseo de tener una familia estaba en desacuerdo con ello. Entonces, ¿cuáles han sido realmente los éxitos de tener una gran familia, hacer arte, tener ese tipo de estilo de vida más fluido y no tradicional?

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Los éxitos son que es muy generador, ya sabes.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Sí.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Piensas que me refiero simplemente a volver a lo que dijo este profesor, ¿no? Como si estuviera diciendo lo contrario. Él está proponiendo esta idea de que eso no es generador, que no generarás nada, ¿verdad?

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Correcto, correcto.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Y lo que descubrí es que es extremadamente generador en muchos, muchos sentidos. Solo quiero decir que fui muy prolífico, ya sabes, porque siempre estaba en el estudio y una idea podía surgir en cualquier momento. Y me doy cuenta a través de esa idea que no tuve que ir a un estudio separado para hacerlo. Y luego es generador también en el sentido de que de alguna manera afecta a los niños. Verdad. Y algunos de los niños se convirtieron en artistas o diseñadores o al menos en pensadores creativos. Y creo que es generador en ese tipo de formas.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Sí, yo también creo que algo que realmente me llamó la atención de tu trabajo y de este recorrido por la casa es que hay mucho que podemos aprender de los jóvenes. Y yo creo--fui docente durante años; Hice música y teatro, y hay muchas cosas realmente inspiradoras sobre los niños. Me pareció realmente interesante cómo tu trabajo realmente se basa en las ideas creativas y el entusiasmo de tus propios hijos y también de tus alumnos. ¿Puedes hablar sobre cuál es la cualidad o cuáles son algunas de las cualidades que obtenemos de los jóvenes y que tal vez otras personas no tengan? Cuando los adultos dicen que no les gustan los niños. ¿Sabes de qué se están privando, realmente?

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Bueno, empezaré hablando de las personas mayores volviendo a esos profesores. Ya sabes, cuando estaba en la escuela, había algo así como desanimar extremadamente a tus estudiantes, ya sabes, ese era el enfoque cuando estaba en la escuela de arte. Era esta idea de poner a tus estudiantes en dificultades y aplastarlos para que, ya sabes, en primer lugar, probar si son capaces de ser artistas. Bueno. Creo que esa era una de las funciones de tratar a los estudiantes con tanta dureza y crítica. Pero también, sí, la idea de hacer que profundicen un poco más. Pero sentí que mucha gente estaba aplastada. Ya sabes, mucha gente no se dedicó al arte porque eran, las críticas eran muy duras. Pero lo que encuentro es que sí, los jóvenes tienen mucho, hay muchas promesas. Hay tanta, tanta emoción. Hay tanta claridad que me gusta aprovechar. Me encanta estar cerca de eso. No me gusta estar cerca de personas mayores que están, ya sabes, como, cuál es la palabra cuando están cansados cuando, sí, son negativos. Cuando son críticos. No me gusta esa energía. Sabes, trato de mantenerme lo más lejos posible de eso. Me gusta estar cerca de gente joven que tiene grandes ideas y mucha energía, y me gusta apoyar eso. Pero también me gusta aprovechar eso, ya sabes, e impulsarse desde ahí y, entonces, sí, colaboro regularmente con personas que son más jóvenes que yo. Pero sí, quiero decir, lo considero un momento de enseñanza, pero también lo considero un gran momento de aprendizaje. Y pienso en el aula de esa manera. No se trata sólo de lo que podría darles a los estudiantes, sino también de lo que puedo obtener de esa experiencia, y eso es lo que la hace más emocionante. Creo que a veces los profesores se cansan, ¿verdad? Porque -

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Sí.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Simplemente enseñan lo mismo de siempre y eso es aburrido. Pero lo que sucede cuando llegan nuevas generaciones de estudiantes artesanos es que se trata simplemente de nueva información y nuevas posibilidades.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Sí, poder aprovechar eso. Eso es lo que siento como artistas adultos y a lo que todos estamos tratando de volver: ese tipo de creatividad desenfrenada. Durante el recorrido por la casa hablaste de algunos autorretratos que has coleccionado a lo largo de los años. ¿Puedes hablar con ellos?

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Sí, yo, yo, iría, comencé esto, no sé cuándo comenzó, probablemente fue como justo después de la orden de quedarse en casa en la pandemia. Empecé a ir a la Escuela del Instituto de Arte de Chicago después de que terminó el semestre, al departamento de pintura para recoger pinturas, para tomar las pinturas que dejaron, ya sabes, para usar, reutilizar los lienzos o para escoger pinturas que me gustaron y poder colgarlas en mi casa. Y como ocurre con todo, con el tiempo surgió un enfoque. Y yo diría que el enfoque fueron los autorretratos, porque yo pinté muchos autorretratos cuando era un joven estudiante. Y para mí, hay algo muy potente en ellos, ya sabes, simplemente que tienes este tipo de expresión cruda de los estudiantes, tienes su presencia, tienes su espíritu en la, en la pintura. Y entonces los estudiantes los dejaban porque a veces, muchas veces al final del semestre, porque los estudiantes no son de aquí, son de Chicago, y vuelan a donde sea. Simplemente dejarán pinturas. Y sí, mi atención se enfocó en los autorretratos porque, porque me atrajeron. Y como llevo tanto tiempo enseñando y los cuelgo, comencé a colgarlos en la escalera de mi casa para subir. Solo porque también sentí que era un espacio de tránsito, ¿verdad? Y sentí que era un buen espacio para poder tener este contacto o esta conexión con estos estudiantes para mí, como enseño todo el tiempo. Entonces, es una manera de representar mi enseñanza, aunque no conozco a estos estudiantes, siento una conexión con ellos.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Sí. ¿El autorretrato suele ser una tarea temprana cuando estás comenzando la escuela de arte?

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Suele ser, todavía parece que es un encargo que se da, en el primer año de enseñanza de pintura. Pero creo que los estudiantes simplemente se sienten atraídos por hacerlo de forma natural. Pero. Sí. Y probablemente surgieron de tareas para hacer un autorretrato. Y una de las cosas que hago cuando veo estos autorretratos es que trato de no juzgarlos, ya sea bueno o malo. Sólo los colecciono. Y creo que podría pensar que uno es malo, pero cuando está en la pared con todos los demás, se comunica de una manera diferente.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Sí. ¿Qué consejo le darías a alguien que siempre se sintió atraído por el arte, las artes visuales, las artes escénicas y que no sabía realmente por dónde empezar?

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Creo que hay que empezar por cualquier lado. Y simplemente ser persistente con esa cosa. Creo que realmente podrías empezar por cualquier lado. Hay algo arbitrario en crear que creo que es asombroso. Sólo eso, quiero decir, pintar es fácil. Ya no, ya no pinto mucho realmente. Pero, ya sabes, si comenzara a trabajar en un lienzo, podría hacer cualquier trazo. Podría hacer cualquier cosa. Podría ser un muy mal trazo. Y, por supuesto, lo que tiende a suceder es que tienes dudas sobre ese trazo, pero es la acumulación de trazos y la persistencia y la creencia de que algo va a salir bien te ayuda a superarlo. Y no sabes qué es, ¿verdad? Y estoy usando pintura, pero creo que podría estar relacionado con cualquier cosa. A cualquier cosa como tomar fotos en mi teléfono. Como algunos, como yo, podrías mirar mi rollo de fotos. Por ejemplo, si tomo una foto, a veces la hago entre 30 y 50 veces porque tomo una cosa al principio y creo que ya la tengo, pero no es hasta que la hago 30 veces más que empiezo a concentrarme, en el plano de la imagen, la luz. Algo sucede en la luz. Me doy cuenta de que algo es lo más interesante de esa imagen. Así que creo que eso tiene que ver con la perseverancia y la creencia de que algo está ahí, pero solamente hay que, hay que de veras profundizar un poco más.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Sí, creo que esa confianza es la parte difícil. El juicio del trazo es la parte fácil. Y luego creo que la confianza para seguir adelante es la parte difícil.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Lo es, pero tampoco lo es, si lo piensas... quiero decir, es algo difícil, pero en realidad es un estado mental, si piensas así y lo haces bien. Esa es la otra cosa. Te vuelves bueno en creer en lo que estás haciendo.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Sí.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Pero hay que ponerlo en práctica.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Sí.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Y no se me hace gracioso porque yo, y sé que para algunas personas existe, pero para mí personalmente, yo no creo en absoluto en el bloqueo artístico. Porque yo hago esto. Creo que he establecido algo en mi práctica, que estoy usando la palabra generador nuevamente.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Sí.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Eso es generador, que las ideas nunca puedan dejar de fluir. Porque, antes que nada, me he vuelto bueno en esta creencia, ¿verdad? Y en segundo lugar, tengo este tipo de perseverancia. Y sí, configuro una especie de sistema generador para que siempre salga algo, no importa lo que haga, siempre saldrá algo.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Esto está totalmente en consonancia con todo lo que sé sobre cómo la gente ha tratado de documentar y entender la creatividad es que es algo así como la motivación. ¿Verdad? Si estás sentado y no haces nada, no te sentirás motivado. Una vez que empieces a estar activo.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Yeah.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Mágicamente te sentirás motivado. Me recordaste una cita, no la recuerdo palabra por palabra, de Jim Henson de Los Muppets. Hubo una gran exposición sobre él, creo que fue el Museo de Ciencia e Industria hace un montón de años. Había una cita en la pared que decía: "Siempre hay ideas dando vueltas". Sólo tienes que estar abierto para atraparlas. Y parece que has descubierto cómo trabajas y has creado ese sistema para que incluso estando en tu casa y veas resultados de la creatividad, ¿verdad? Ver que las cosas tangibles que has hecho y que puedes compartir, simplemente fluyen. Pero que eso venga de algún lado para que no tengas que estresarte por un bloqueo artístico.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Yeah.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Preguntando por un amigo que conoces.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Y a mí, no no no no, sí me gusta la palabra abierto.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Sí.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Es una palabra sencilla.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Sí.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Ya sabes, permanecer abierto. Ya sabes, creo que de eso estoy hablando cuando, los artistas, la gente se cansa, ¿verdad? Es que ellos se cierran. Y, ya sabes, también podría estar de miedo, porque podrías llegar a ser muy bueno en cerrarte a ti mismo. ¿Verdad? Y yo, personalmente, nunca quiero que eso me pase a mí. Ya sabes, no quiero encerrarme tanto que no haya nadie a mi alrededor. Una de las razones y no tengo nada en contra de pintar porque todavía pinto de vez en cuando. Pero creo que para mí esa es una de las razones por las que decidí que no quería ser pintor, porque había una especie de soledad en esa forma de trabajar con la que ya no quería continuar. Sabes, no quería simplemente estar en el estudio trabajando en estas pinturas. Sé que algo maravilloso saldría de ello. Pero a costa del sacrificio de algo.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Sí. Quiero decir, es una especie de deseo universal de incluso en la vida laboral. ¿Qué tipo de trabajo me gusta hacer? ¿Cómo es esto sostenible? ¿Cómo va a traerme esto tanta alegría como pueda, mirándolo también dentro de la vida artística? Supongo que nunca había pensado en ese tipo de matices entre, bueno, puedo hacer esto, tengo talento en esto. Puedo dedicarle tiempo, pero no me va a dar lo que quiero día a día. Y mucho de lo que escucho son decisiones activas para perseguir las cosas que te traen alegría, perseguir las cosas por las que sientes curiosidad natural y realmente hacer crecer esto. Y al hacerlo, eso es lo que mantiene esta apertura. Quiero decir, se relaciona con trabajar con estudiantes y trabajar con jóvenes tal como ellos piensan, ¿verdad? Es como, bueno, eso es interesante. No tengo miedo de eso. Bueno. Bu bu bu bu.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Yeah.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Noté algo sobre lo que quería preguntarte. Siento que el humor aparece mucho de una manera sutil en tu trabajo e incluso en nuestro recorrido, hay muchas capas y yuxtaposiciones realmente interesantes. Creo que hay música clásica sonando en tu baño ahora mismo y me interesa: ¿piensas en el humor? ¿Es algo que simplemente sucede? ¿Cuáles son tus pensamientos?

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Sí, creo que sucede, naturalmente. Creo que el humor es importante. Y es, y ya sabes, tal vez, tal vez también te refieras a ello como juego. Pero al igual que yo, creo que para mí el juego y el humor son importantes para el proceso artístico porque, nuevamente, simplemente lo hacen más divertido.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Sí.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Eso es una cosa. Pero creo que la vida es así, también suceden cosas divertidas en la vida.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Sí.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Y observo esas cosas, y, a veces, las observo, ya sabes, accidentalmente, o simplemente a través de, simplemente suceden coincidencias, que son, que son humorísticas o, pero pienso en términos de juego. Hay algo en el juego que es como, estaba hablando de la foto en la que puse el tendedero sobre esa especie de higuera cuando estaba en España, en un apartamento como allí, no sé qué significa eso. cuando juntas esas dos cosas, pero ese tipo de acto divertido de poner algo donde no pertenece, crea un nuevo significado. Y creo que es a través de ese nuevo significado o ese humor que te conectas con el espectador, ya sabes, si no lo es, si no lo hay, como una especie de humor o acto de juego. Sí. Podrías conectarte con el espectador, pero a mí me gusta que el espectador tenga algún tipo de revelación o encuentro al ver mi trabajo. El mismo encuentro que tengo al ver esos dos objetos que no pertenecen. Me gusta compartir ese momento con el espectador. Y luego ese momento evoca algo en el espectador. Y todo lo que les hace reír, les hace felices.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Me di cuenta de eso, esa foto que nos mostraste del tendedero con el árbol a través de él. Lo primero que pensé fue en la historia y ¿quién es este personaje que seca su ropa alrededor de un árbol? ¿Cómo llegó el árbol allí? Estoy pensando en el árbol. Y luego dije, oh, claro, esta es una foto. Ya sabes, eso me hizo pensar instantáneamente. Es una forma muy divertida de conectarse con alguien.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Bueno, eso está relacionado con esta palabra abierta que usas antes. Yo estaba escribiendo algo el otro día sobre eso. Estoy tratando de recordar. Era la idea de mantener las cosas abiertas para el espectador. Si tuviera que crear una pintura que fuera muy expresiva y simplemente le pusiera un cierto sentimiento, ya sabes, como si yo o yo contase un tipo de narrativa muy específica, tiene el potencial de cerrar un poco la lectura. Como si simplemente pusiera mis propias emociones en eso, directamente en una obra de arte, entonces se trata de esa emoción, donde encuentro que si solo observo y me gusta incluso ser objetivo. Es gracioso porque lo fáctico es lo opuesto al humor. Como a veces cuando hago movimientos fácticos o simplemente observo, y no incluyo mis propias emociones en ello. Y luego le presento algo al espectador, siento que hay más apertura donde el espectador puede aportar sus propios pensamientos, en lugar de que yo le diga a alguien qué pensar.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Sí, eso tiene mucho sentido. Y esta es una especie de transición perfecta hacia la curaduría que estás haciendo para Chicago Humanities en solo unas pocas semanas, un día entero de arte y experiencias. ¿Y te importaría hablarnos un poco de un adelanto de lo que...?

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Yeah.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Cómo se ve eso.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Totalmente. Bueno, primero que nada, es un día entero, lo cual me hizo sentir un poco confundido. Era como si todo esto fuera a suceder en un día. Pero a medida que avanzaba, tenía sentido y tenía perfecto sentido dentro de mi práctica, ya sabes, crear una experiencia que dura todo el día. Y supongo que no todos se quedarán durante todo el asunto, pero yo estaré allí. Y estoy muy emocionado por las cosas que se reunieron para este programa de este día, y la forma en que se unieron fue, fue, fue, fue un proceso creativo muy interesante. El programa, inicia con la Iglesia Museo, en el auditorio del Museo Nacional de Arte Mexicano. Vamos a hacerlo, es domingo. Así que pensé que era apropiado tener una iglesia, algo que se pareciera a un servicio religioso. Entonces mi buen amigo Jorge Lucero va a dar un sermón. En realidad es hijo de un pastor, pero su sermón será un sermón etimológico. Así que vendrá con su diccionario de etimología en lugar de la Biblia. Y le gustará analizar una palabra durante el sermón. Jesse Malmed va a estar certificado como si pudiera casar gente. ¿Cómo le llamas a eso?

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Ordenado. Yo también fui ordenada. Creo que técnicamente soy como Rabina ordenada Rosenthal. No soy rabino, pero estoy ordenada.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Sí, exactamente. Él es. También fue ordenado. Pero él en el pasado casó forma y contenido. No sé qué va a casar esta vez, pero si casa, bien podría casar ideas o casar objetos inanimados, inanimados. Y luego están dos artistas de sonido que van a actuar, ya sabes, ¿qué es equivalente a la sección de oración de una iglesia? Y entonces ese es el primer programa. ¿Bueno? Y luego habrá comida, ya sabes, como donas y café después. Como ocurre a veces en la iglesia. Y luego se irá directamente a la conferencia de Harry Gamboa Jr. Harry Gamboa Jr., si no lo sabes, es miembro del grupo ASCO de la década de 1970, un artista chicano que hizo un trabajo realmente sorprendente y radical del que yo no sabía nada. Por alguna razón, nunca estuve expuesto a esto en las clases de historia del arte. De hecho, una vez mi hija me envió un ensayo y me dijo: tienes que leer este ensayo. Y era verano. Y pensé, en mi cabeza, que no voy a leer un ensayo en el verano. Pero ella seguía molestándome por ello. Y finalmente me senté en la hamaca y leí este ensayo, y este trabajo me dejó impresionado. Ella estudia en Occidental College en Los Ángeles y ese es su enfoque. Como si realmente se concentrara en el trabajo de ASCO. Así que invité al miembro fundador Harry Gamboa Jr. a dar una conferencia y luego nos dirigimos a la galería, PACH o Galería "pack". E invité a seis artistas a hacer trabajos en respuesta a los primeros trabajos de ASCO. Y por lo que tengo entendido, la fundación, los miembros en realidad todavía estaban en la escuela secundaria cuando comenzaron este movimiento, este grupo, que vuelve a hablar de artistas jóvenes, son muy conocidos por esta pieza llamada Spray Paint LACMA. Estaban en el Museo del Condado de Los Ángeles y no pudieron, esto fue en los años 70. No pudieron encontrar ninguna representación de artistas chicanos. Entonces iban con el curador y le preguntaban: ¿por qué no hay ningún artista chicano en el museo? Y el curador dijo algo así como, ya sabes, que los artistas chicanos son pandilleros y grafiteros. Entonces, esa noche, los miembros del grupo pintaron con spray todos sus nombres en el museo. Y tienen esta foto histórica de ese momento. Y lo más interesante es que desde entonces el Museo del Condado de Los Ángeles ha tenido una retrospectiva gigante de su trabajo y tiene muchas de sus obras en su colección. Entonces eso es lo que está pasando. Seis artistas, María Gaspar, Josh Ríos, Nancy Sánchez, entre otros, van a representar las nuevas versiones de estas obras de ASCO o nuevas interpretaciones de estas obras. Y luego termina el día en el estacionamiento del Museo Nacional de Arte Mexicano, donde invité a 18 artistas a mostrar sus autos, autos con instalaciones.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Genial.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Autos con escenarios que tienen programación en la parte trasera, autos que están cubiertos con una bandana gigante. Habrá una variedad de cosas y se llama Auto Portrait Spectacular. Es un juego de palabras, como autorretrato, auto retrato. Y luego, la noche realmente termina con tres músicos que tocarán en el escenario del estacionamiento.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Muy divertido.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Y se está yendo un poco más hacia la música screamo o heavy metal.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Quiero decir, el metal acaba de aparecer en la ceremonia de apertura de los Juegos Olímpicos.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: No vi eso.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Sí. Gojira, a lo largo del Sena.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Wow.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Era metal, así que creo que está teniendo su momento. Sí. La cantidad de yuxtaposiciones y simplemente. Parece un día realmente especial. Sé que la gente saldrá y se la pasará bien.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Sí, estaré todo el día. Y creo que si alguien está todo el día allí será una experiencia para recordar.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Ah, sí. He hecho algunos de esos días de vecindario. Todo el día. Es. Es como un maratón que te hace sentir, duermes profundamente al día siguiente. Es bueno. Tengo una última pregunta para ti. Como gran parte del día, y especialmente porque estarás allí todo el día, conocerás a muchos extraños, y siento que esto es algo que he encontrado mucho en las cosas que estás haciendo. Y aquí estamos. Nos habíamos conocido una vez antes, pero por lo demás somos extraños, ya sabes, y ¿qué esperas en este día completo de programación que realmente te hará interactuar con extraños?

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Bueno, esa es una buena pregunta. Tengo que pensar en ello. Me emociona conocer gente y escuchar sus respuestas. Es curioso porque antes no me gustaba conocer extraños. Verdad. Yo era una de esas personas que se sentía realmente incómoda en un salón de clases con discusiones en el aula o en una mesa en una boda donde estabas con extraños. Pero me he vuelto bueno en eso porque me he aventado a esas situaciones. Solía hacer estas cenas con extraños, hace unos años. Y de hecho, una cosa que olvidé mencionar es el mole de 50 ingredientes que también se servirá, que es mi mole característico que se compone de 50 ingredientes. Esta idea es como traspasar los límites de la cantidad de ingredientes que se pueden poner en una salsa, antes de que se deshaga. Eso, y siempre pensé en ese mole como una metáfora de reunir a extraños. Ya lo sabes. Porque recuerdo cuando iba a hacer estas cenas, le dije a mi, mi mamá que iba a hacer este mole de 50 ingredientes. Y ella dijo: "No va a funcionar". Hay demasiados ingredientes. Y luego pensé, ya sabes, al final tiene que saber a algo. Entonces yo diría que eso es lo que espero con ansias. Solo espero con ansias el collage de personas que estarán allí, tanto como los artistas que muestran los autos, cierto, pero también como las personas que experimentan estos momentos y cómo responden a ello. Va a ser interesante también.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Bueno, no puedo esperar. ¿Cualquier otra cosa que quisieras...

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Yo..

ALISA ROSENTHAL : …..mencionar?

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Podría seguir y seguir y seguir. Bueno, lo último que quiero mecionar es. Sí, ve a ver la exposición en el Museo Cleve Carney del College of DuPage. Doy…como que.. doy visitas guiadas a la gente. College of DuPage está un poco lejos de la ciudad, pero allí hay magia. Y me gusta mucho encontrar magia. Y encontré la magia en ese lugar y, de hecho, llevo a la gente a través de él. No sólo mi exhibición, sino también la reserva en la parte trasera de la universidad. Como si hubiera una energía mágica allí a la que me gusta llevar a la gente mientras ven mi espectáculo, porque también mejora la experiencia del espectáculo.

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Eso es perfecto. Eso es todo. Alberto, muchas gracias.

ALBERTO AGUILAR: Gracias. Gracias.

[Suena el tema musical]

ALISA ROSENTHAL: Para obtener más información sobre Alberto Aguilar y el día de los eventos que ha curado para el Pilsen Day Art & Experiences de Chicago Humanities el 29 de septiembre, diríjase a las notas de la exposición o directamente a chicagohumanities.org para registrarse en los eventos gratuitos.

Chicago Humanities Tapes es producido, editado y presentado por mí, Alisa Rosenthal, con asistencia de producción, edición de historias y redacción del equipo de Chicago Humanities.

Los nuevos episodios se publican los martes cada 2 semanas donde quiera que obtenga sus podcasts. Asegúrese de hacer clic en "seguir" para recibir alertas cuando haya nuevos episodios disponibles. Si te gusta lo que escuchas, danos una calificación, deja una reseña o comparte tu episodio favorito. Volveremos en dos semanas con un episodio nuevo para ti. Pero mientras tanto, sigue siendo humano.

[Suena el tema musical]

[El reproductor de casetes hace clic para cerrarse]

SHOW NOTES

MOSTRAR NOTAS

Alberto Aguilar ( L ) and Alisa Rosenthal ( R ) at Aguilar’s home studio.

Alberto Aguilar ( I ) y Alisa Rosenthal ( D ) en el estudio de la casa de Aguilar.

The Artist in Residence is part of Art Design Chicago, a citywide collaboration initiated by the Terra Foundation for American Art that highlights the city’s artistic heritage and creative communities. The Artist in Residence is funded by the Terra Foundation for American Art.

El Artista en Residencia es parte de Diseño de Arte Chicago, una colaboración en toda la ciudad iniciada por la Fundación Terra para el Arte Americano que resalta el patrimonio artístico y las comunidades creativas de la ciudad. El Artista en Residencia está financiado por Terra Foundation for American Art.

A closeup of Alberto Aguilar’s dining table made of Chicago Public School tables.

Primer plano de la mesa de comedor de Alberto Aguilar hecha con mesas de Escuelas Públicas de Chicago (CPS).

Framed photo from Alberto Aguilar’s wall.

Foto enmarcada del muro de Alberto Aguilar.

Explore:

PACH Pilsen Arts & Community House

The Cleve Carney Museum of Art at the College of DuPage

Your Art Disgusts Me: Early Asco 1971-75

Explorar:

Casa comunitaria y artística PACH Pilsen

El Museo de Arte Cleve Carney en el College of DuPage

Tu arte me repugna: principios de Asco 1971-75

Programmed by Lauren Pacheco

Producing assistance from Sam Leapley

Edited and mixed by Alisa Rosenthal

Recording assistance from David Vish

Podcast story editing by Alexandra Quinn

Copy assistance from Katherine Kermgard

Spanish language transcript editing by Laura Crotte

Programado por Lauren Pacheco

Asistencia de Producción de Sam Lepley

Editado y mezclado por Alisa Rosenthal

Asistencia de grabación de David Vish

Edición de historias de podcast por Alexandra Quinn

Asistencia de copia de Katherine Kermgard

Edición de transcripciones en español por Laura Crotte

Subscribe: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/chicago-humanities-tapes/id1534976656

Donate now to support programs like this: https://www.chicagohumanities.org/donate/

Explore upcoming events: https://www.chicagohumanities.org/

Suscribir: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/chicago-humanities-tapes/id1534976656

Done ahora para apoyar programas como éste: https://www.chicagohumanities.org/donate/

Explore los próximos eventos: https://www.chicagohumanities.org/

Recommended Listening | Escucha recomendada

- Podcast

- February 20, 2024

Throwing Poems into Lake Michigan with Sandra Cisneros

- Podcast

- March 19, 2024

Lin-Manuel Miranda Shares the Secrets to Making Great Art

- Podcast

- July 11, 2023

Joan Baez on Music, Art, and Lifelong Activism

Become a Member

Being a member of the Chicago Humanities Festival is especially meaningful during this unprecedented and challenging time. Your support keeps CHF alive as we adapt to our new digital format, and ensures our programming is free, accessible, and open to anyone online.

Make a Donation

Member and donor support drives 100% of our free digital programming. These inspiring and vital conversations are possible because of people like you. Thank you!