Sarah Smarsh shares how education enabled her to transition from “being broke” in rural America to becoming a journalist and writer. Caitlin Zaloom reminds us that college degrees help people get well paying jobs that offer economic stability. And Mary L. Gray discusses the dangers of unregulated labor markets. Watch these archival videos to discover the power of labor.

"What I hope that this book does...is facilitate a conversation about an area, a place, a people, a region, a concept that has been reduced largely in our national discourse to a one-dimensional thing, often a negative thing, sometimes a sentimentalized thing. Heartland is and has been...all of those." —Sarah Smarsh

Sarah Smarsh, author of Heartland, grew up in the poverty of rural America, She was the first woman in her family to go to college instead of becoming a teen mother. “University,” Smarsh recalls, “was the moment when I [did] something that nobody from where I came from had, and thus rendered me forever different from the place that I love and come from.” Smarsh, who studied hard for scholarships and worked multiple jobs to pay for college, remembers the pain she felt when the experiences of low-income first generation college students were “not acknowledged by the person that’s eating a sandwich between pieces of bread that came from wheat that you watched your family's fingers bleed to grow and harvest.”

“College is an indispensable part of the condition of aspiration.” —Caitlin Zaloom

Cultural anthropologist and author of Indebted, Caitlin Zaloom believes America’s higher education system is “fundamentally broken.” She characterizes admissions and financial aid processes as exclusionary practices that compound already existing socioeconomic and racial inequality: “African America families who don't start with family wealth, who have faced discrimination in the labor market and aren't paid as much...these conditions end up eroding their ability to pay [for college],” Zaloom says. What’s one way to repair for this injustice? Treat higher education as a public good rather than a private asset by making tuition free.

"What is it going to take to be able to develop an orientation, a new social contract that supports a commons, that imagines the future of work not as moving back to full-time employment but literally moving toward providing a way for people to do their work but also live their lives?” —Mary L. Gray

Can computers do anything humans can do, but better? No, says Ghost Work author Mary L. Gray, because people have two things technology doesn’t: “creativity and snap judgement.” If a situation doesn’t have a clear “yes” or “no” answer, chances are a software program can’t be written to solve the problem, Gray explains. Cue ghost work: an unregulated labor market of “cognitively draining” “tasked-based” employment that keeps the internet running: “We don't have the economic models to think about this employment,” Gray cautions, because ghost workers are “ephemeral and ambient” to the market, they are not protected. This system “sets up [a] devaluing of people,” Gray notes, “and in many cases it allows companies to sell what they sell as the magic of AI or the magic of tech.”

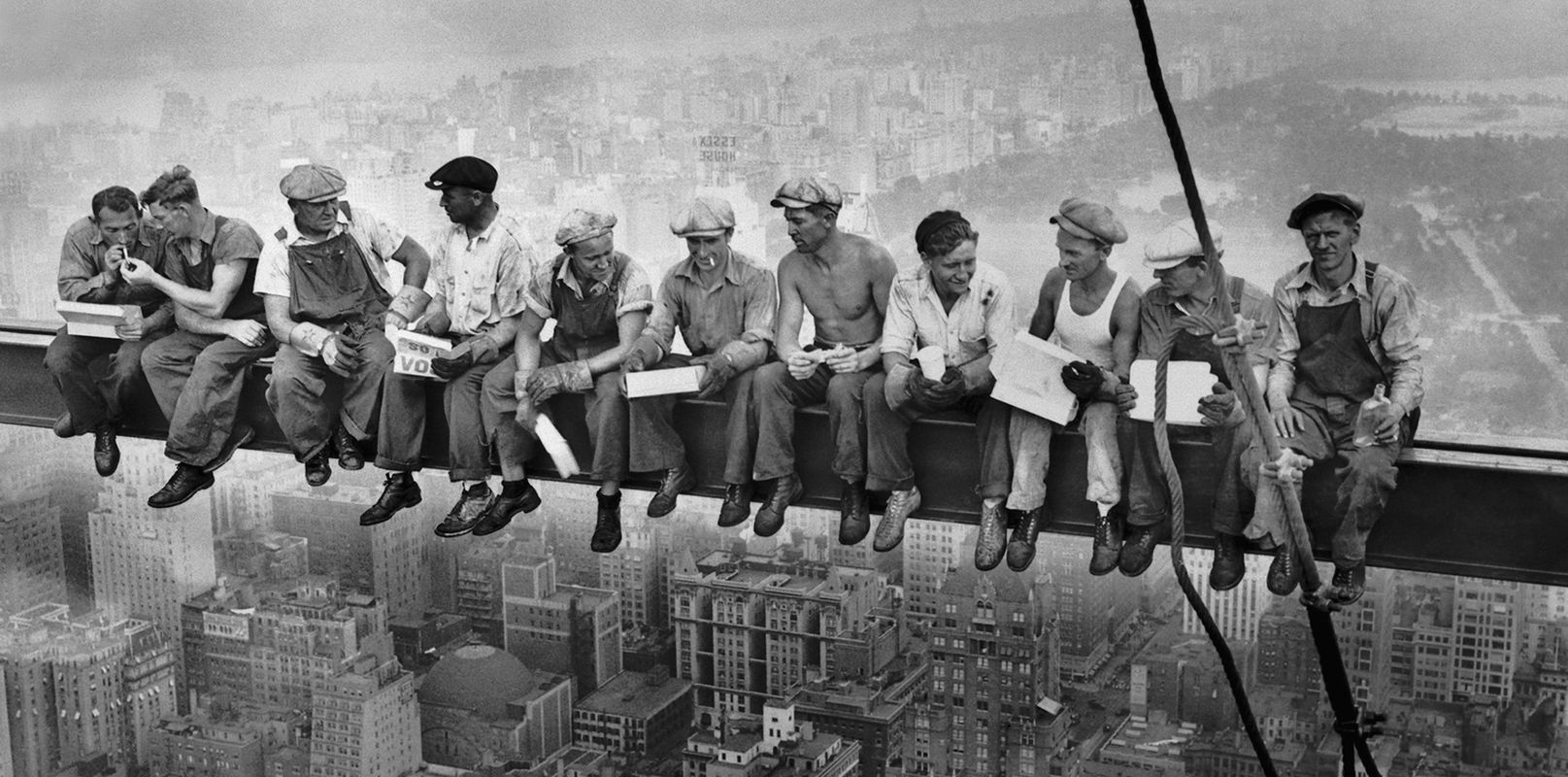

Header image credit: Lunch atop a Skyscraper (1932)

Become a Member

Being a member of the Chicago Humanities Festival is especially meaningful during this unprecedented and challenging time. Your support keeps CHF alive as we adapt to our new digital format, and ensures our programming is free, accessible, and open to anyone online.

Make a Donation

Member and donor support drives 100% of our free digital programming. These inspiring and vital conversations are possible because of people like you. Thank you!