"The web is going to be very important….It's certainly not going to be like the first time somebody saw a television….It's not going to be that profound."

– Steve Jobs, Wired, 1996

Implicit in the Graphic! theme this year is an assumption about contemporary society: that we’re uniquely obsessed with images at this particular historical moment. Anyone who takes public transportation can attest–it certainly seems like many of us are glued to our pocket-sized screens. Around 95 million photos and videos are shared on Instagram every day, and as of August 2018, the platform has a new “Your Activity” feature so users can track how much time they’re spending on the app. Moreover, data shows that streaming video and audio accounts for 71% of primetime internet traffic across North America. In sum, there’s plenty of evidence–anecdotal, observational, and data-driven–that we’re living in an image-saturated society.

But is our sense of being inundated by images especially contemporary? What about when television sets invaded our homes in the 1950s? Television refashioned our domestic space and spurred debates around the corrosive nature and inexhaustible diversions of electronic media, not to mention the controversial role it’s played in politics–leading to what some scholars called a “crisis of communication for citizenship.” And what if we looked back even further, to pre-cinematic technologies, the advent of photography in the 19th century, and the subsequent preoccupation with physical movement and “arresting motion” through film?

Cultural histories might suggest that while visual technologies are decidedly different today than in 1959 or 1834, our response to what feels like a dense, omnipresent stream of images has its own history. Streaming the latest animal memes on YouTube while riding the bus may seem light years away from marveling at a magic lantern’s moving shadows in the back of a 19th century British pub–but the sense of wonder at evolving visual technologies is profoundly human. In short, we may feel that our lives are more graphic than ever before, and perhaps it’s true–but guess what: generations before us have felt this way, too. We offer five ways of historicizing our contemporary “graphic” behavior.

Trachtenbuch des Matthäus Schwarz | 1560 | HERZOG ANTON ULRICH MUSEUM | via The Atlantic

1) The selfie has a rich legacy in art history.

What does Kim Kardashian have in common with 16th-century German accountant Matthäus Schwarz? They both understand how the selfie–and its intrinsic commodification of self-awareness–reinforces social hierarchies in their favor. And, they both published books of selfies (some argue that Schwarz published the first fashion book). Art critic Jerry Saltz, a part of our 2018 Fall Festival, suggests that the selfie is in fact a distinct genre with discernible characteristics, and may have begun with an Italian late Renaissance self-portrait in 1523. The selfie as self-portraiture, it seems, was recognizable as a form long before Snapchat or even the Kardashian-spurned duckface.

Claude Lorrain, "Port de Mer au Soleil Couchant" | 1639 | PUBLIC DOMAIN

2) We’ve always been trying to capture that gorgeously illusive golden hour.

The original image filter (or mediation effect) is actually not #sepia but probably the Claude glass, named for the 17th-century French painter Claude Lorrain. Similar to a filter on your phone, this convex tinted glass was used by travelers to soften and frame beautiful landscapes and render scenic views all the more memorable. By widening the view and changing the tonal values of a scene, the Claude glass (or Claude mirror) helped artists and tourists to frame and visually represent landscapes according to prevailing picturesque ideals. Today, alterations in color tone and contrast are just a tap away and a lot more numerous on our phones, from Aden to Vesper and everything in between–but it seems we’ve been trying to soften our images to appear just so for centuries.

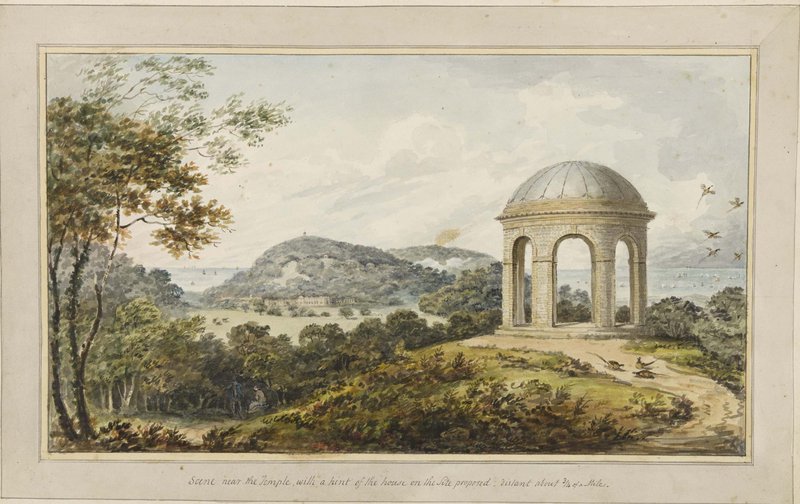

Humphry Repton, Sheringham Park | National Trust

3) Image curation is big business–just ask Instagram influencers.

Beauty, capitalism, and the pursuit of authenticity: these forces not only butter the (artisanal, gluten-free) bread of many an Instagram influencer today, they also created a whole new set of aesthetic criteria–an “artificial naturalness”–in 18th-century Europe. The sale of curated images potentially has roots in “the picturesque”–an aesthetic category from this period, according to critic Daniel Penny. He argues that contemporary practices around Instagram curation and picturesque aesthetics are linked not only by formal techniques and framing, but also by “shared bourgeois preoccupations with commodification and class identity." This mode of aesthetics was marked by a highly constructed picture that appears to be natural–a kind of stylized impression of faux antiquity. The picturesque was concerned with eclecticism and giving the impression of an “unvarnished” natural landscape, so much so that fake ruins called “follies” were constructed on the estates of the wealthy to give the appearance of age and history–an antecedent to the shabby chic design you can find in the decor aisle of your local big box store. So the next time you’re tempted to post a photo of your açaí bowl in faux-antique china and set against a "rustic" cottage or barn-inspired backdrop, take a moment to consider whether you actually enjoy eating a bowl of purple goo and the textual layers or if you’re doing it, as they say, for the gram. Either way, Jane Austen would probably identify with the way you're signaling prosperity and refinement.

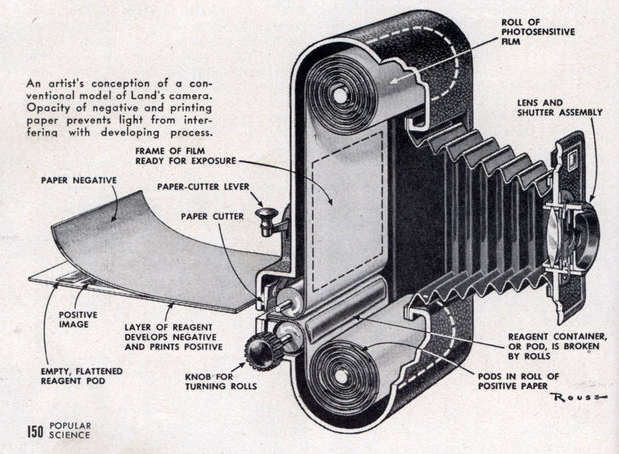

Popular Science | May 1947

4) Our inclination for instant pictures originates with Dr. Edwin Land, not Steve Jobs.

Obsessed with kaleidoscopes, stereopticons, and stereoscopes as a child, Land studied optical science and the physics of light and prisms, and aspired to remedy the dilemma of blinding automobile lights at night. His polarizer technology was able to reduce the glare from light, and had influential applications in the military. In the 1940s, Dr. Edwin Land spearheaded new visual technology that consolidated the 11 painstaking steps formerly required to develop and print a conventional photograph: a one-step camera that took the first Polaroid photos. Dr. Land created the instant Polaroid in 1943 and with it, the craving for immediate pictorial gratification. So while digital photos today have several undeniable advantages (including truly instant photos), the original revolution for photographic temporality occurred well before the iPhone was invented.

Canaletto, "Piazza San Marco from the Southwest Corner" | ca. 1724–80 | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

5) “Pics or it didn’t happen”: 18th-century style.

Beginning in the late 1600s, fashionable and well-to-do young aristocrats would embark on a tour of Europe, traveling to Paris, Venice, Florence, and Rome as a culminating experience of their classical education. This tradition of the “Grand Tour” was a rite of passage for the wealthy meant to spark inspiration, enlightenment, discovery, and adventure. And, these travels also inspired the creation of portable visual records of the cities–called vedute–in the form of drawn or painted landscapes and cityscapes. Anticipating souvenir postcards and perfectly-framed contemporary Instagram vacation photos, these elevated, highly detailed, and often manipulated paintings gave an air of authenticity and refinement to these aristocratic European travelers. Thus, the 18th-century phenomenon of vedute not only prompted a new kind of artistic practice, but also crystallized the idea that the visual record of having travelled somewhere is just as important–perhaps even more important–than the actual experience of traveling: consecrating the postcard from far away as a status symbol.

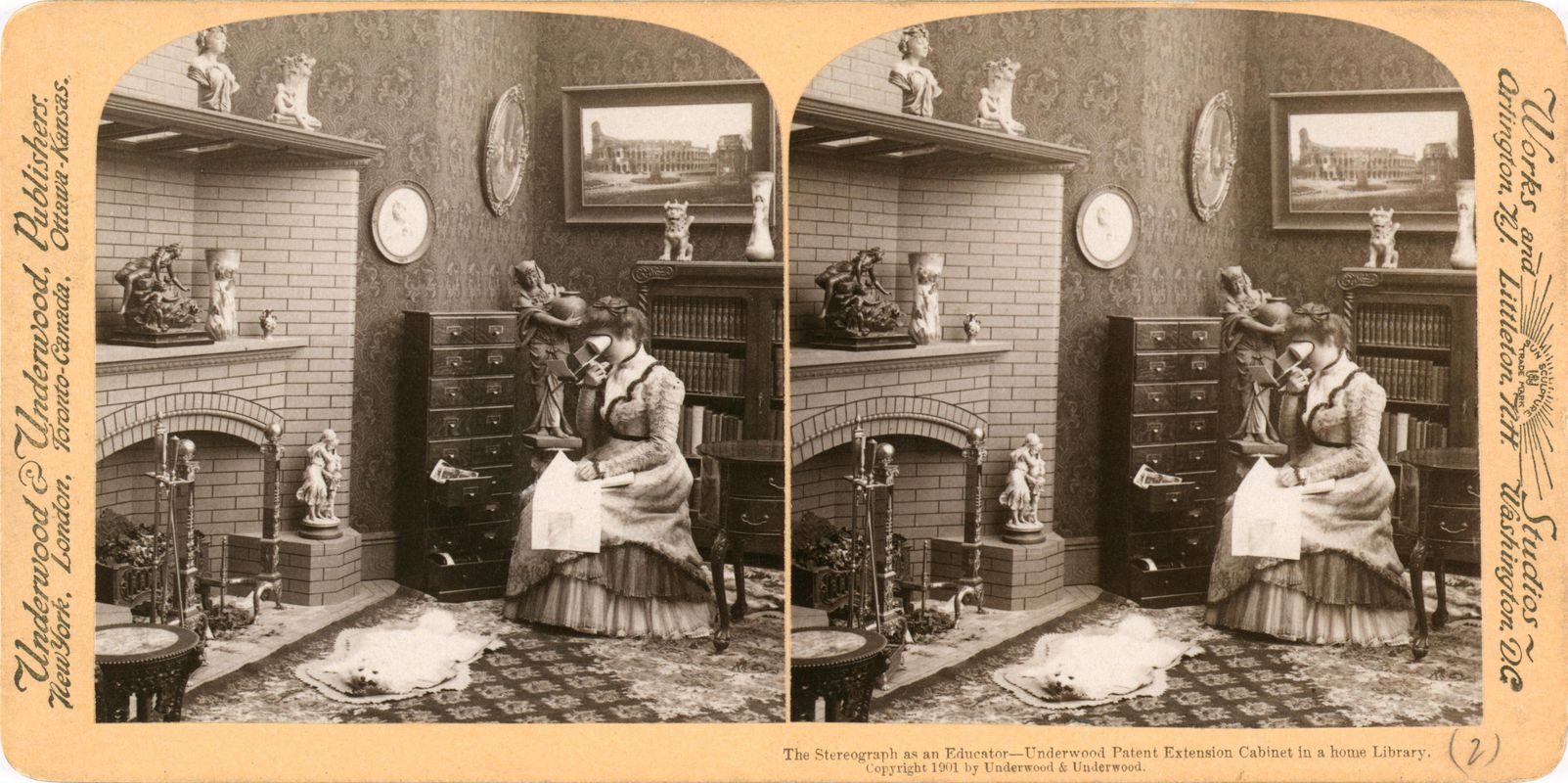

Header image: "The stereograph as an educator" | 1901 | Public domain

Become a Member

Being a member of the Chicago Humanities Festival is especially meaningful during this unprecedented and challenging time. Your support keeps CHF alive as we adapt to our new digital format, and ensures our programming is free, accessible, and open to anyone online.

Make a Donation

Member and donor support drives 100% of our free digital programming. These inspiring and vital conversations are possible because of people like you. Thank you!